Guest blog by Cintia Smith, IPP ’23

I started the IPP program a year after beginning the analysis of the public issue we were addressing, which, in our case, was “the malfunctioning of municipal service to deliver procedures due to bureaucratic burdens.” Just when we were about to start implementing the governmental digital services and procedures platform, I became familiar with PDIA. For this reason, my considerations in this blog will focus around the lessons the course provided me when it is time to implement public innovation projects.

The key lessons I obtained from the course are precisely related to the logic of learning itself. I mean that when we step out of the university educational environment and transfer knowledge to the public sector, there is a mistaken belief that there is no room for trial and error, and that every implementation of public policy has to be effective from the start. In this course, I learned that it’s actually the opposite. We must be prepared for processes of learning and adaptive adjustment. That resilient capacity will be what allows public policies to be executed and scaled. My new vision thanks to PDIA is: “Never give up and adjust your strategy once and again.”

During the months of project implementation, I could summarize the challenges into two types of issues. Firstly, the difficulties in driving the work through an internal cross-functional team focused on project results within our department of innovation. Innovation projects are very stressful and uncertain, and the boundaries of action for each internal team and the medium-term results are not clear. Insisting on a flexible matrix of activities with people in charge and execution dates can smooth the path.

Secondly, another significant challenge is the resistance from the executing areas, which incorrectly perceive these reforms as an outside input that jeopardizes their control over the processes and, eventually, their jobs due to possible technology replacement. Building trust and cooperation within a specialized team of this nature is a slow process that requires a combination of co-creation and pressure dynamics to achieve results, but trying to do so in the most cooperative possible way.

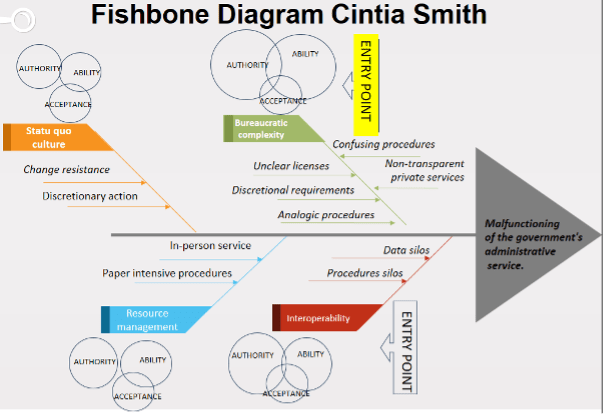

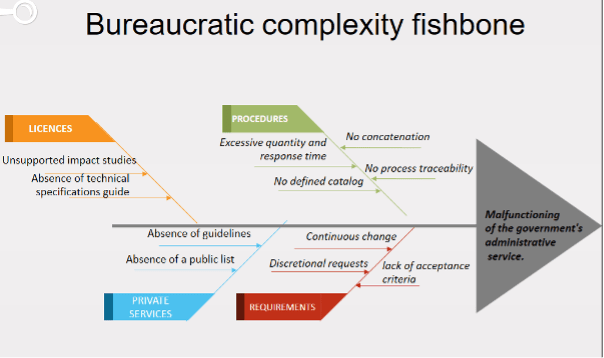

In the case of our project, the issue had already been extensively worked on with officials and business chambers for a year, so in this case, the use of the fishbone diagram served to outline the diagnostic information that was already available.

In the following graphics, I break down the problem into two dimensions. The first focuses on all possible entry points, and the second specializes in the selected entry point, zooming in on this topic.

I found very interesting the approach to the dimensions of authority, capability, and acceptance to define entry points. These courses of action had already been defined prior to starting the IPP course, but it allowed me to give new dimensions to previous decisions. I used to work with the problem tree methodology, which is similar to the fishbone one. It’s important to highlight that this kind of problem-oriented approach is very useful when we are starting the diagnostic phase, and I intend to continue using them in the future.

Since I started the IPP program, what I put in practice are adaptive implementation recommendations. Forming small cross-functional teams that identify corrections through trial and error exercises and quickly adjust the strategy were the greatest suggestions for implementing policies.

Another learning from IPP is the recommendation to build a coalition of vertical and cross-cutting authorizers to drive public innovations. This coalition proved to reinforce the innovation agenda inside the cabinet.

Finally, after completing the IPP course, I would like to share the following recommendations with the PDIA community of practitioners:

1. Public issues have a cross-cutting logic: you need internal and external allies to advance your agenda. Start by building this network.

2. The authorization process is a messy one. Don’t worry. Work its top-down logic, but also build a bottom-up validation.

3. Policy implementation is an adaptive process of teaching and continuous improvement. You need a small team flexible enough to respond to this demand.

4. Good projects are the result of an efficient multidisciplinary team. Build it, develop their capabilities, and then listen to them and learn to delegate.

I feel very lucky to be part of the PDIA community throughout the world.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. 47 Participants successfully completed this 7-month hybrid program in December 2023. These are their learning journey stories.