written by Matt Andrews

I teach international development policy and management courses – to degree program and executive students. Twenty years ago, my classrooms were dominated by people from what we used to call (and still call) ‘developing countries’. These are typically poorer countries in the global south, that are the prime customers of development organizations and NGOs. I saw my job as working with folk from these countries, which was what differentiated my work from other non-development-oriented public policy and management academics.

The composition of my classrooms has changed in the last decade, however. I have many more students from higher income countries in the global north – especially in executive education – deeply interested in learning about ‘development’. At the same time, my non-development colleagues are finding an increased interest in their classes – on topics like negotiations, persuasion, 21st century leadership, and more – from poorer countries in the global south.

This has caused me to reflect on what I now believe ‘development policy and management’ is about.

My reflection starts with a perspective I have about public policy work in general, which I see as ‘the activities governments and related entities undertake to address collective challenges in society’. These activities happen all the time, in every corner of the world – regardless of how poor or rich or north or south a country may be.

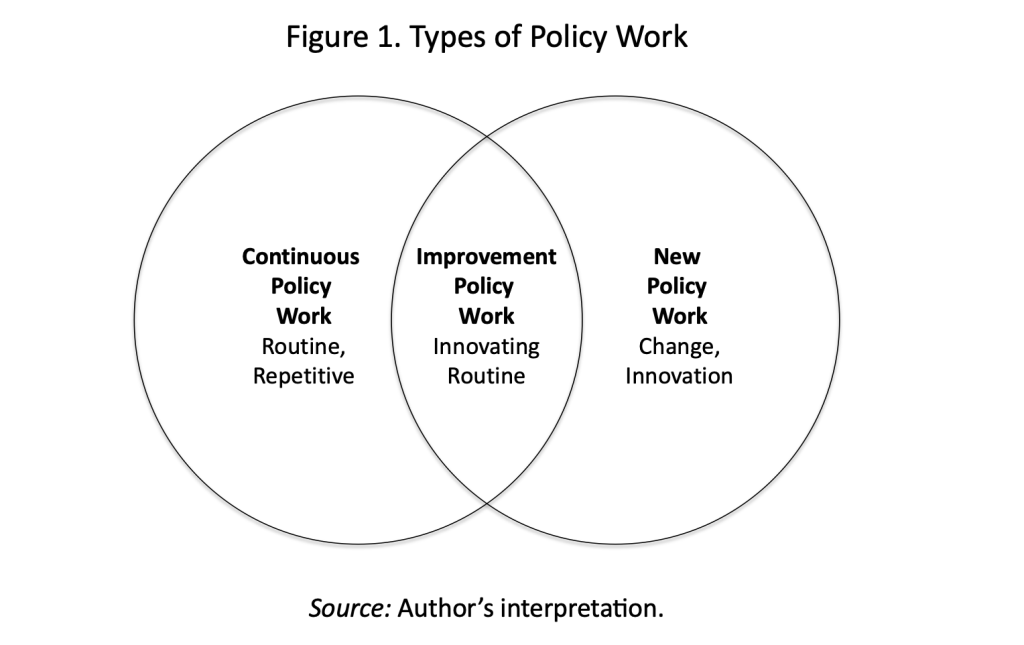

Inspired by literatures on continuity and change and continuous improvement in organizations – amongst others (see March (1996) and Berger (1997), for instance) – I have started to pay attention to the different types of policy activities we undertake:

- Some activities are ongoing and continuous, taking the form of routine and repetitive processes (like issuing passports in many countries, for instance, or registering motor vehicles in entities that have existed for fifty years).

- Other activities are new, involving change and innovation (like current responses to emergent climate change challenges in many countries).

- A third type is blended, with some degree of novelty introduced to improve established policy work, again implying some level of adaptation (like health system reforms to account for new disease burdens).

I show these three types of activity in Figure 1 below, suggesting that most if not all policy work implies one or more of the types – and most policy actors face work in one or more of the domains shown. I have tested it out with many policy professionals – in all parts of the world – and find that they commonly relate easily to the types. And they commonly – in rich and poor and north and south contexts – tell me they are always working on all three.

Interestingly, most definitions of ‘development’ emphasize change as a (or the) defining characteristic – A Cambridge dictionary definition, for instance, holds that it is ‘the process in which someone or something grows or changes and becomes more advanced’.

Given such definition (and there are many others), I have thus come to view that two types of policy work that involve change are essentially ‘developmental’. These are policy activities focused on ‘new’ or ‘improvement’ work. In such thinking, I see ‘development’ happening in rich and poor contexts all the time, as societies face pressures to change and evolve in response to shifting problems, opportunities, and other realities. I also see ‘development policy and management’ as work that all public-leaning entities do at some time or other, regardless of the context they are in.

This ‘development policy and management’ work is what governments and related entities do when they pursue activities that imply and involve change for any part of the social collective.

“It is less about a set of countries or geographically located people and more about the challenges policy actors face – in all countries and geographies – that require an element of change for novelty and improvement.”

It may be true that there is more such work in poorer countries in the global south, given historical legacies and the emergent nature of many modern governance and economic systems in those countries. But all contexts face the need for change, and all governments (and related entities) are struggling with policy challenges that involve novelty and improvement.

I think this is why so many people are coming to ‘development’ sessions from places we never viewed as ‘developing’. And this is why I – and my colleagues at Building State Capability – are shifting our view about what ‘development policy and management’ is about!

References

Berger, A., 1997. Continuous improvement and kaizen: standardization and organizational designs. Integrated manufacturing systems, 8(2), pp.110-117.

March, J.G., 1996. Continuity and change in theories of organizational action. Administrative science quarterly, pp.278-287.