Guest blog by Silvia Steisel, IPP ’23

My role as a leader in a philanthropic organization focused on employment has led me to the realization multiple times that we were attempting to address complex issues in an inadequate manner. Employment is a multifaceted sector influenced by various cyclical, cultural, social, and political factors. Challenges related to employment span from issues of access and equal opportunities to health, skills, job creation, job destruction, technology, aging, and more. How does one tackle these problems? Where does one begin? How does one navigate the complexities, especially in a country where employment is heavily influenced by public policy? How can a smaller, private philanthropic funder make a meaningful impact?

Personally, as a member of a group of young leaders @Belgium 40 under 40, I embarked on a collaborative effort with peers to address a challenge we ourselves faced: how to effectively balance parenthood and employment. As the first generation experiencing the new norm of both parents working, alongside evolving family models and increased demands in the labor force, we observed potential risks to our mental health and that of our children. Many female friends were reducing or abandoning employment due to these challenges. The more we delved into the issue, the more we realized that something needed to change. It wasn’t just a problem to solve; it was a context demanding transformation.

I invested significant time in searching for methodologies, guidelines, and shared experiences, eventually discovering the Harvard Kennedy School’s “Implementing Public Policy Program,” where I was introduced to the Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) method.

Key learnings from my nine months of action learning included adopting the mindset reflected in Einstein’s quote: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” PDIA reinforced the idea that, when faced with complex issues, our reflex is to jump to solutions without truly understanding the problem. The starting point is learning, reading, talking, but most importantly, listening to those intimately familiar with the context of the problem. Continuous questioning, particularly asking “why” five times, is crucial.

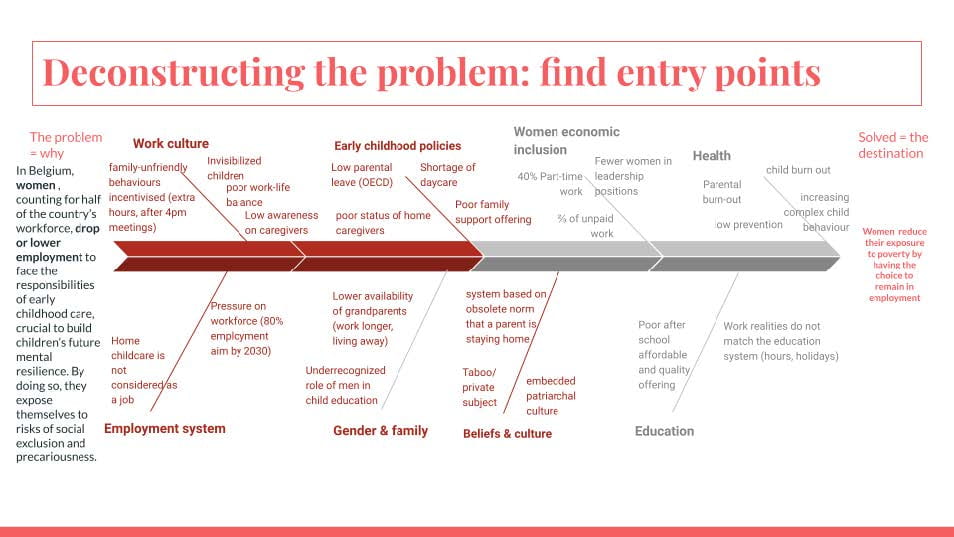

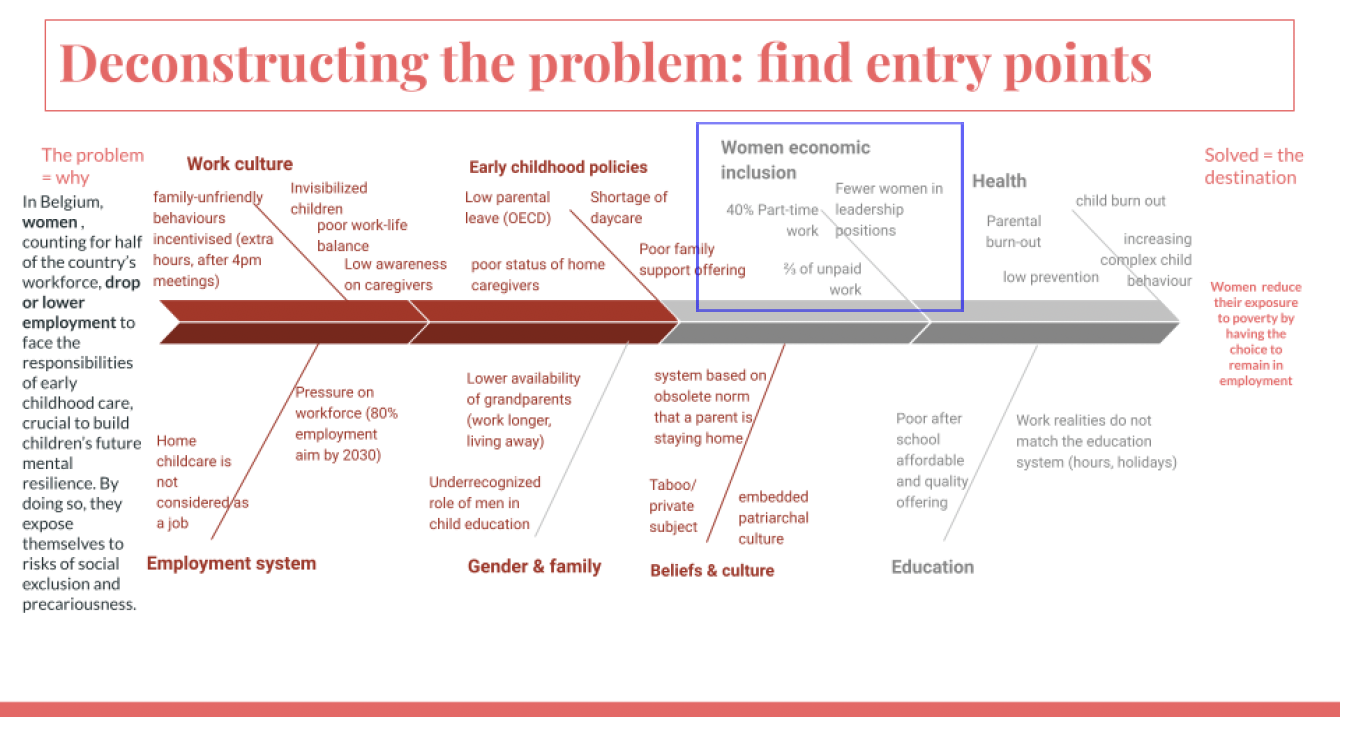

These insights allow you to deconstruct the problem, identify sub-problems shaping the context, and use tools like a fishbone diagram to distinguish causes from consequences. This process helps identify entry points—specific aspects of the problem you choose to address first.

Personally, finding the right entry point for the challenge of combining parenthood and employment was challenging. Is it the mental health of children, an aspect universally recognized as important but seemingly distant from employment? Is it tied to Belgium’s political goal of 80% employment by 2030? Or is it related to parental burnout or women’s participation in the workforce? The struggle lay in not reducing it solely to a “women’s issue.”

From the chosen entry point, you build your narrative. Crafting a compelling, concise statement about a complex problem is difficult but essential for mobilizing people and assembling a team with authority, ability, and acceptance (AAA). I rewrote my problem statement numerous times, testing every option.

A breakthrough occurred unexpectedly when the Nobel Prize in Economics 2023 was awarded to Claudia Goldin, a Harvard professor specializing in women’s employment and the impact of parenthood. This reinforced my entry point—women’s economic inclusion—and provided both authority and increased acceptance within the philanthropic community. The statement became clear: In Belgium, women, comprising half the workforce, reduce or abandon employment to manage early childhood care responsibilities, crucial to build children’s mental resilience. By doing so, they are exposed to social exclusion and precariousness.

Moving forward, the usual approach to problem-solving involves identifying best practices from elsewhere. However, I learned about the concept of “positive deviance,” where the problem doesn’t occur in a specific context. In my case, this means seeking out companies where women don’t reduce their employment participation, understanding why, and consulting with those who successfully navigate parenthood and employment. It’s often a matter of common sense rather than complex science.

PDIA transformed my approach to problem-solving, applicable across various contexts. I used it to assist an entrepreneur in reviewing strategy and identifying entry points for change. It also reshaped my perspective on project management in public policy and the role of philanthropy in designing iterative solutions.

The challenge of combining parenthood and employment began as a discussion among concerned citizens, and Harvard Kennedy School provided the structure through the PDIA methodology, adding a “women employment” lens. I proposed to the foundation I am leading to recycle these learnings to address the issue in the context of Belgium’s 2024 elections, and it was approved. We want to put this topic on the radar for progress in Belgium, acknowledging the challenges and uncertainties, but remaining open to change, adaptation, and retrial—lessons instilled by PDIA.

To fellow PDIA practitioners worldwide, I share the words of Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. 47 Participants successfully completed this 7-month hybrid program in December 2023. These are their learning journey stories.