Guest blog written by Rebecca Trupin, Prateek Mittal

Our PDIA journey began with our authorizer, a senior bureaucrat in the State Government of Meghalaya, sharing a document with us about his vision to build capability of the state administration to deal with complex problems. We had been working with him on local governance-related projects and were keen on institutionalizing adaptive problem-solving processes. We suggested that he try a few pilot projects in different sectors to understand and document how a PDIA approach could work in the state. At that time, he had recently taken over the health department and improving maternal and child health indicators had become one of his priorities. We decided to focus on the complex problem of high maternal mortality in the state.

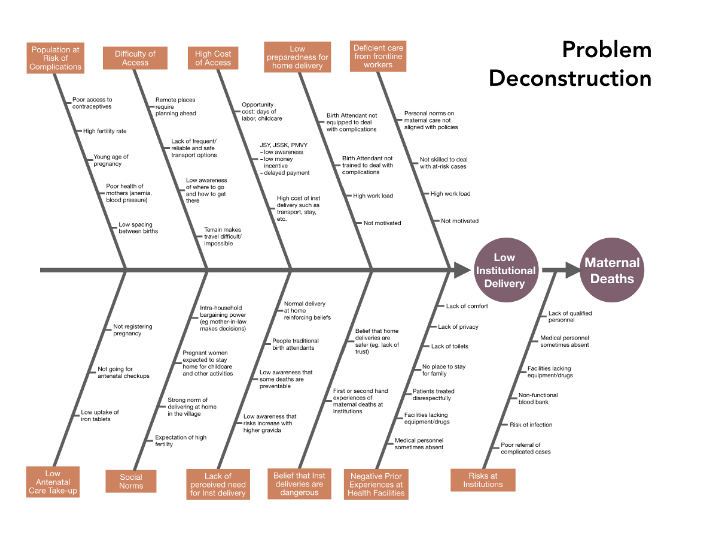

We had several late night/early morning interviews, courtesy of the 10-hour time difference, with different stakeholders and had weekly check-ins with our authorizer. Through this process, we mapped the various causes of maternal deaths in a fishbone diagram that helped us visualize the complexity of the problem.

Based on this, we generated some ideas that could be useful in learning more about the problem and help the health department better prioritize resources towards issues that can give them some strong gains in the short-term. We used this work to make a case for building a PDIA team in Meghalaya that could build on this and make some tangible progress on improving maternal health outcomes in the state.

As we reflect on the process, we want to share three things about three things that capture our key learnings and takeaways for anyone who is interested in doing PDIA.

Three things we learned

1. Evidence can come from many different sources and many different forms

When we started the project, we tried to get quantitative data on maternal health indicators. But we quickly realized that data was not easily available and available data was not particularly reliable. We thought this might seriously undermine our ability to understand the problem. However, we collected several stories, experiences and ideas that helped us understand the different perspectives that people had about the problem. For instance, we documented several stories that helped us understand how prior experiences at healthcare institutions of a few individuals could heavily influence other community members’ future decisions to seek maternal care in institutions.

2. Complex problems are often either ignored or substituted for something less complex

Most of the people that we spoke with substituted the problem of maternal death with the problem of institutional delivery, which is somewhat more tractable. There is an implicit assumption that higher institutional delivery would lower maternal mortality. But there is not enough discussion on whether the focus on institutional deliveries limits our ability to understand the full complexity of the problem.

3. Experiences often don’t translate into learning

Every person we spoke with had insightful stories and personal experiences that shaped their understanding of the problem and potential solutions. These perspectives, however, are very much siloed and, as such, they don’t become part of the collective learning process. One of the key moments of our PDIA journey came when our authorizer participated in an interview with a community outreach coordinator. During that conversation, our authorizer found out that there were community peer educators active in many villages who could play an important role in generating demand for maternal care.

Three things we recommend

Our experience over 8 weeks contained a lot of lessons, some unique to our project, and others which seem applicable for anyone doing PDIA or other complex projects.

1. Build in time for reflection and big picture thinking

As we went deeper into the weeds of our problem, we began to realize acutely the need to build in time for reflection. Since PDIA usually involves a problem with many unknowns, thinking holistically is essential. The PDIA weekly check-in includes the question, “What did you learn about the problem?” which is meant to help spark this bigger picture thinking. Yet, it can be all too easy to answer the question narrowly and miss the reflection opportunity.

Another reason to step back and reflect is that team members often develop different interpretations of the same events. Was the government avoiding dealing with maternal mortality, or making a good faith effort? Did our key informant believe that the demand-side of maternal health services was more of a constraint, or was it supply-side? Without making time to discuss and reflect on our evolving perceptions it was easy to get out of sync, not to mention, miss out on opportunities to expand each other’s’ thinking.

2. Organization is key

Organization is essential for any project involving multiple people, and especially when the project is complex, with many stakeholders and contacts. We kept all meeting and class notes in one google document, with a navigation pane to find things easily. Here, we also crafted agendas for upcoming meetings, and language to send to potential interviewees. As our interview list approached 20 people, we added status trackers and began to follow this closely. One take-away is not to wait to develop these tools – start using them at once! More importantly, review these organizing tools regularly to keep track of stakeholder engagements, questions and ideas to follow up, and to reflect on overall learnings.

3. Diversify perspectives sooner rather later

As our fishbone diagram indicates, many different causes and types of actors touch maternal mortality. It brings in everyone from the village headman and mothers and their families, to health center staff, NGOs, and District Commissioners. Initially we found ourselves speaking mostly with government employees. This probably limited the pace of our learning since it took some time before we began to hear more about how the government approach itself might be flawed. It would have been helpful to ensure a higher diversity in stakeholder perspectives from the outset.

Three things we will carry with us

1. Curiosity over expertise

Problems with a medical component are assumed to require great expertise. Yet, maternal mortality has many non-medical components. The behavioral and cultural aspects are particularly hard to understand fully, let alone target through government policy. We found several of the most knowledgeable stakeholders ready to admit their ignorance, while those further from the problem were more likely to espouse conventional wisdom or simplified explanations. Given an aim of really unpacking causes, the first attitude, of humility and curiosity, seems essential to avoid jumping to conclusions and allow learning to emerge from the work.

2. Balancing quick wins with addressing binding constraints

Solving complex problems has a key disadvantage: it is hard to see progress toward the goal. PDIA overcomes this to some degree by breaking a large problem down into smaller, more concrete parts, within which it is easier to measure progress. Moreover, PDIA involves focusing on those elements of the problem that are addressable. If the work stopped there, however, we would likely never translate small steps into significant change. We must also address those causes that are binding constraints, even if only little by little. One of the secrets of PDIA is balancing accomplishing quick wins to build momentum and retain authorization, with tackling the thornier elements of the problem.

3. Who is doing the problem-solving is just as important as how the problem is being solved.

Governments tend to rely on external consultants and experts to deal with complex problems. However, stakeholders that are embedded in the system often have both the best understanding of the problem and ideas that could be effective in the context. In such cases, the role of external stakeholders should be more of facilitators who bring different perspectives together and facilitate collective learning. This approach can also help reduce dependency of governments and local stakeholders on external expertise in the long run.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2020. These are their learning journey stories.