Guest blog by Anna Rhee, Barkha Tripathi, Naomi Beyth-Zoran, Freddy Guevara

Key Learnings from the Course

Working in teams: As aspiring policy practitioners, we never thought as fundamentally and structurally about group-work as we did in this course. Oftentimes, work is not mobilized or its potential remains unmet because people are struggling to align and keep working together. This course showed how imperative it is to have a solid working dynamic with your group and how that shows in the final outcome. For us, the team-work process was fairly smooth because we kept accountability to each other and to our authorizer as the baseline throughout the 6 weeks. We were consistently available for each other, and tried our best to pick up the submissions, stakeholder conversations, and so on whenever someone on the team could not meet their share of the work. The team spirit and camaraderie were high throughout, and especially remained intact during mild disagreements. Because most of us could not collectively engage with all stakeholders, we came in with different questions/perspectives to team meetings, and it was challenging to align on the “head of the fish” as we kept iterating. However, most of us found the process of brainstorming valuable for our individual learning! We learnt a lot from each other each week.

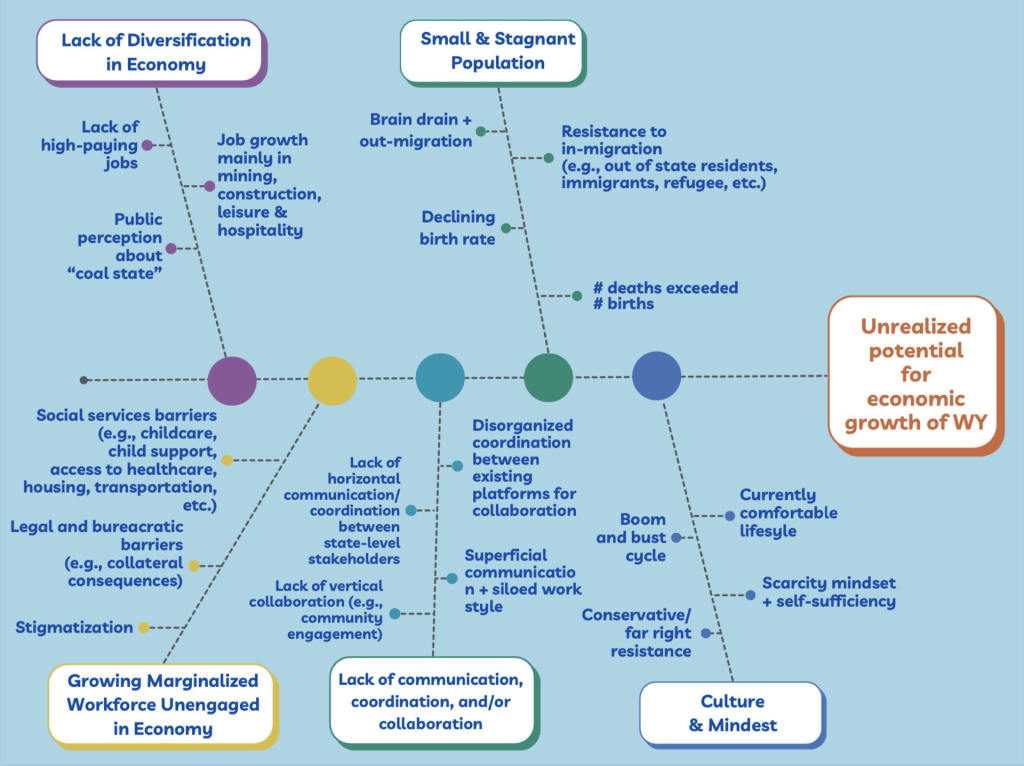

Unknown/Complex Problems require a discovery-led approach and constant iteration: This course illuminated how important it is to keep asking questions and keep looking for the problem, and not rush to a solution. Especially with our project, the “head of the fish” that we began with (re: reengaging JII into the workforce) was far away from how we saw the problem by the end– and the authorizer was also aligned with this idea. The problem was certainly bigger than how the authorizer was looking at it initially, and had many causes/sub-causes to it. Had it not been for the PDIA framework, we might have jumped to looking at the problem from the JII-reengagement perspective and proposed solutions accordingly. By taking the problem as “yet to be defined” and constantly evolving, we were able to be more curious with all stakeholders we engaged with and productively critical with the authorizer.

Talk to people– and help people talk to each other! One of the biggest collective learning our group had from our project was– every time we spoke with a new person in the system, a new and important piece of information emerged, that opened new possibilities to look at the problem construction. We tend to underestimate the idea that usually the people who the problem belongs to, also hold possibilities of effective and innovative solutions. As designers, we rarely need to propose a new thing. The capacity exists but remains to be discovered. Talking to people also made us realize that so much work is already happening in the state with the problem as we identified it. Since week 3, we were mostly hearing about the lack of alignment and “superficial” meetings between all relevant stakeholders who can mobilize work as the authorizer wants to (re: the lack of coordination, collaboration, and communication as an entry point to our problem). If only the authorizer could get the right people to care enough to act on the issue right now, the work can be mobilized. For that to begin, their convening is key.

Progress and Insights on the Problem

Gaining Insights on the Problem is a Dynamic and Incremental Process: Upon initiating the PDIA process with the authorizer, the problem statement emphasized the challenges of addressing the unmet job vacancies in Wyoming which was exacerbated by the State’s decreasing population due to declining birth rate, prevailing outmigration of young working-age individuals, and rising numbers of baby boomers retiring from the economy. Ultimately, the initial understanding of the problem was determining how to incorporate justice-involved individuals to resolve the unmet workforce demand in WY. However, the team quickly realized that spending adequate time in the problem construction and problem deconstruction phases of the PDIA process is critical in accurately determining the actual problem rather than relying on preconceived ideas and assumptions. Not rushing through the problem deconstruction phase and engaging in in-depth discussion with the authorizer led to the discovery that the underlying problem in WY was the lack of ability and acceptance towards economic growth.

Words of Wisdom to Students and Practitioners

Working with PDIA is not easy. It may look relaxed and low-pressure, but in fact, it places the responsibility for the process in your hands. Engaging quickly and thickly requires a fair amount of intentional, well-targeted learning. It builds on picking a direction to drill down on, researching and swiftly deciding if and when to turn to another path.

Having a supportive, grounded authorizer is a key element in the process. They are not there to tell you where to go in your inquiry, but to extend information, contacts, and most of all their insights on the questions you present in order to define the problem as accurately as possible. Try and “read” their responses to your ideas, and make sure to register them as “data” for your next step. Talk openly amongst yourselves to debrief conversations with the authorizer.

Letting go of the ambition to “solve” the problem is not the only thing you need to do. You also need to accept the fact that you most probably will not even have any new ideas or new entry points. You will not reinvent the wheel in any way. What you can achieve is providing the authorizer with a fresh perspective on the problem, raising questions that may be new, and allowing them to look at the problem through a “stranger’s” eye.

Another contribution you might have is helping your authorizer to reconnect with their constituencies, in cases where the authorizer is in a leadership position and while having the best of intentions, they might be at some level of disconnect from people on the ground – the beneficiaries of the desired policies.”

“Don’t be afraid to step away from the problem statement and rephrase it completely. It’s actually the most exciting part of PDIA. A bell ringing, telling you what you’ve missed, or a novel way to shape the fishbone – these are moments when you can say that you’ve learned something about the problem.

One of the biggest wants is the will to be present for implementation – having spent a fair amount of time figuring out the problem and suggesting ideas – it’s only natural to want to see what becomes of it. For this part, we have no answer, unfortunately.”

Fishbone Diagram

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2024. These are their learning journey stories.