Guest blog by Alexandra Lastra Andrade, Bran Shim, Giovanna Lia Toledo, Mannat Singh, and Courtney Young

“The Drive Alone Mode is too high.” In a span of just six weeks, our team was tasked with learning and applying Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) to understand what this statement meant to us—and what it meant for the people of New Orleans.

We are a group of public policy students trained in economics, urban planning, and finance with experience spanning the public, private, and non-profit sectors. We were presented with the challenge of car ridership in New Orleans, a seemingly simple problem but one that we would come to realize was incredibly hard to address. With group members from Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, India, and the United States, it was safe to say that none of us were familiar with the issue we were about to tackle. Fortunately, we were led by a team of experts who guided us along the way. Matt Andrews and Salimah Samji presented us with clear frameworks to breakdown a problem and iterate along the way. Derek Chisholm, a senior-level project manager at AECOM, who served as our authorizer, brought expertise in the field of transportation in New Orleans and helped us develop a nuanced understanding of the issue.

Through weekly group meetings among ourselves, the teaching team, and our authorizer, along with countless readings and conversations with stakeholders, our team constantly learnt and unlearnt the problem. While this was surely a bumpy ride, our team emerged out of the PDIA process with a clear understanding of the problem and actionable strategies to solve it.

PDIA METHODOLOGY: KEY LEARNINGS

Trust the process

With limited time to both understand and begin tackling a complex issue, the turnaround time is fast and can seem initially overwhelming. However, we trusted the process and pushed ourselves to keep moving forward and keep an open mind. Despite moments of confusion and frustration, our team remained hopeful and were willing to iterate on our work, instead of committing to the first draft of anything we prepared.

Have clear entry points

While there may be many root causes of an issue, one may not have the authority, ability, and acceptance to create meaningful change. Mapping key stakeholders and analyzing their power and jurisdiction made us realize that there were areas where little change was possible. Simultaneously, we could see areas where we had direct and indirect entry points. This enabled us to develop strategies for quick wins while expanding critical change spaces to address down the road.

Keep learning

Engaging diverse stakeholders was an immensely helpful learning experience. By speaking with a new person every week, our team was exposed to many perspectives that were not obvious and challenged our initial assumptions. Moreover, several of these insights helped us connect seemingly distinct issues, thereby deepening our understanding of the New Orleans problem and identifying key interventions. The best part about this was that these interactions created a network of leads our authorizer could connect with to implement our recommended ideas!

Don’t reinvent the wheel

During our research, we discovered many good practices that were either latent or being deployed in other parts of the world. Finding ways to build upon these efforts and scale initiatives in New Orleans enabled us to develop potential solutions without duplicating efforts. It also allowed for better collaboration between actors working to solve the same issue.

PROBLEM INSIGHTS

In the PDIA framework, problem construction is a powerful tool to earn the buy-in of key stakeholders and tap into invaluable sources of knowledge. However, our biggest challenge was precisely “constructing” the problem. With the diversity of skills and experiences our team brought, we each had a very different understanding of the issue. This became even more complicated as we delved deeper into research. As we uncovered more data and literature, we found ourselves grappling with too many details and ultimately losing sight of the main issue.

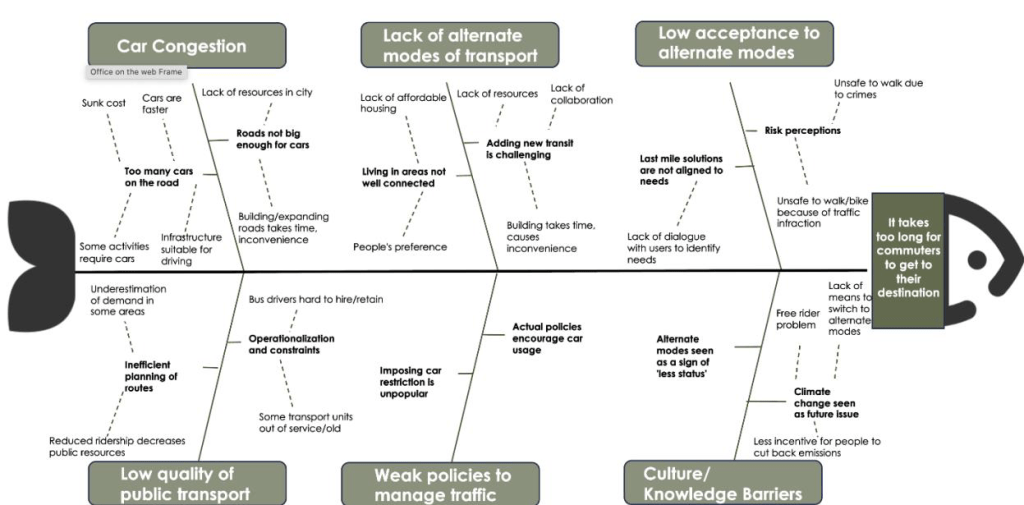

We initially leaped to decarbonization, as it was a key market for our authorizer, and because “mode shift” from private vehicles is most commonly part of the climate change discourse. But as we dug in deeper, we began to recognize that people across New Orleans likely experienced car ridership differently. Climate change could seem like a distant and vague problem. For many people, access to a car could be a lifeline that connected them to work, school, and beyond. They could be frustrated with inconvenient, unreliable, or unviable alternatives. Instead of parachuting in with “best practices” to solve a problem that the people of New Orleans—let alone ourselves!—couldn’t agree on, we pushed ourselves to understand what problem each person would care about. Our team defined and redefined the problem through continual brainstorming sessions, and we experimented with multiple fishbones, merged them together, and moved bones to the head of the fish and back (indeed, our problem was a fishy one!). Despite it being an arduous process, we ultimately arrived at a problem statement that we all agreed with: it takes too long for commuters to get to their destination.

We explored commuting time as our key issue because it could unify stakeholders throughout New Orleans. Our research indicated that commuters who relied on cars were frustrated by traffic congestion and concerned about policy changes that might make things worse. Commuters who instead depended on public transit were already in trouble, with only a tenth of the region’s jobs accessible within a 30-minute commute. We realized both sides faced this problem, so we tried moving it to the head of our fishbone. As we continued unpacking the underlying causes of this problem, we had a crucial conversation with a researcher at the University of New Orleans who highlighted that cars were viewed as a sign of “status,” which also made it difficult for individuals to switch to other modes. Through several conversations like this one, we gained a nuanced understanding of the problem and added more bones to our fish. Not only this, once we had clarity on our problem and its underlying causes, the gaps became increasingly clear and guided the development of our proposed ideas.

WORDS OF WISDOM

The ideas our team ultimately came up with were only possible because of the good practices that we were able to deploy as a group. Some key words of wisdom we wish to share are:

Build Trust

Having a sense of shared trust and commitment are key elements to a high functioning group environment. Each week our teammates shared a token of appreciation with each other. The acts of kindness – that ranged anywhere from sharing job opportunities and memes to making handmade cards and origami – were particularly helpful in fostering a feeling of connectedness. Regardless of the act, our team agreed that receiving the act of kindness made us feel visible and valued in the team. Sharing the act of kindness was even more rewarding as it allowed us to bond with our teammates and provide something that the other person would appreciate. The process of both giving and receiving made us all feel strongly connected with one another and allowed us to work well in the team.

Communication

Communication in terms of key responsibilities, delegation of work and setting clear deadlines is important to help the team stay on track. Our group solidified these practices by drafting and developing a team constitution. The constitution served as a guiding document that provided clarity of work and a mechanism to hold teammates accountable. In this way, our team was able to clearly share progress, vocalize any concerns and seek support where required. Apart from clear lines of communication within the team, we also focused on effective communication across external stakeholders. We met with our authorizer every week and shared our progress, gaps we found in our research and posed questions to him. Transparent communication with our authorizer allowed us to receive constructive feedback and significantly improve our work. Meeting with the teaching team and being honest about our struggles further enabled us to get fresh insights and make quick adjustments without causing disruption.

Leverage team skills

Each teammate possesses unique strengths that must be utilized to produce the best results. This was certainly true for our team. One group member demonstrated strong analytical and deductive skills, swiftly identifying problems. Another excelled in effectively communicating these findings through clear and aesthetic infographics. A different teammate adeptly identified loopholes in our strategy and proposed alternative solutions for consideration. Another supported in bringing together disjoined ideas into a coherent narrative. Lastly, a teammate ensured that our story addressed the audience we were trying to serve and within the jurisdiction of our authorizer.

CONCLUSION

The PDIA process has demonstrated that unique challenges faced in society can be addressed with effective communication, teamwork, and flexibility. Being open to new ideas, revisiting the problem and pulling in more stakeholders are critical to arrive at a problem that everyone would care about and consequently, solve.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2024. These are their learning journey stories.