Guest blog by Jennifer Hale Christy, IPP ’23

I began my Implementing Public Policy journey in May of 2023, eight months into serving as Chief of Staff to the Mayor of Beaverton, Oregon. Before that, I served as the Mayor’s Communication Officer for nearly two years. My journey to public service was unconventional–from seminary to teaching, higher education administration, pastoring, and entrepreneurship–to local government.

While unconventional, there are some common threads: a strong focus on community, a call to service, and communication-focused work. My first date with local government was a neighborhood association meeting I attended as an associate minister of a church in the neighborhood. By the third meeting, I became the chair and started meeting with neighborhood program staff at the city.

I participated in an 8-month intensive leadership program sponsored by the local chamber of commerce designed to strengthen and educate community leaders. Through that program, I became deeply rooted in the people, culture, and institutions that comprise the beautiful place known as Beaverton. I began to look for more opportunities to serve. I started meeting sporadically with Lacey Beaty (then-City Councilor) about one day running for office or working for the city.

Fast-forward through a few years of different jobs and a pandemic, and Lacey Beaty was elected our new Mayor. Our new charter also went into effect, changing from a Strong Mayor to Council-Manager form of government. In her first month, Lacey called and offered me a job. I accepted it instantly and began my crash course in working on the political side of local government in the midst of massive transition.

I drank from that firehose with wild abandon–excited for this new opportunity, mentally stimulated by all that I was learning and the variety of things I was doing day-to-day. My training and education had prepared me well for the communications aspect of my work. Managing a large household and juggling multiple side hustles prepared me for the fast-paced, complex world of supporting a busy elected official. Many years of service in private Christian institutions taught me how to navigate internal politics and power dynamics. But I still had almost no experience with public policy. Since I had recently been promoted into a role involving policy work, I knew I needed training.

When I was presented with the opportunity to participate in IPP, I jumped on it. I expected that attending this program would immerse me in the world of public policy: equipping me with the skills to analyze policies, and providing opportunities to explore how to successfully move a policy from the world of thought into actionized impact in the community. I expected a high degree of formality, tight structures, confusing terminology, and exhaustive rules. What I found was nearly the opposite and it was a refreshing surprise.

One of the first things I learned was what exactly “public policy” means – it’s basically anything the government does to address a problem and further a public interest. As it turns out, I had already been operating in the public policy sphere–just without the framework or language.

I knew instinctively about the importance of people and relationships, even if my type-A, achievement-oriented brain often prioritized tasks and projects when under pressure. Through lectures and hands-on experience, this program reinforced how critical it is to prioritize people and relationships if you want to make progress on your tasks and projects. This absolutely takes more time, but it’s essential to implement real, lasting changes. One of my goals quickly became to strengthen internal working relationships amid the stress and uncertainty of budgetary challenges and public pressures around the city’s homeless response.

Through the problem-driven iterative adaptation framework, I learned to take small steps, reflect and evaluate, stay curious, and build on what I learned. While we all want to see swift, sweeping solutions to our most pressing problems, it’s almost never possible. Instead, iteration is a strategy that reduces both the size and number of risks while increasing the likelihood of success. Again, it takes longer but it works.

There are many dimensions of leadership, and some leaders are naturally gifted in many roles. However, I learned that if you take on too much and embody more than three roles (e.g., authorizer, mobilizer, convener, problem solver, etc.), you’ll paint a target on your back and make it easier for the opposition to take you down. I also learned that it’s not necessarily a good thing to have an authorizer who gives you too much authority because it transfers all the risk to you as the implementer. The work and the risk need to be shared among a team of people working collaboratively.

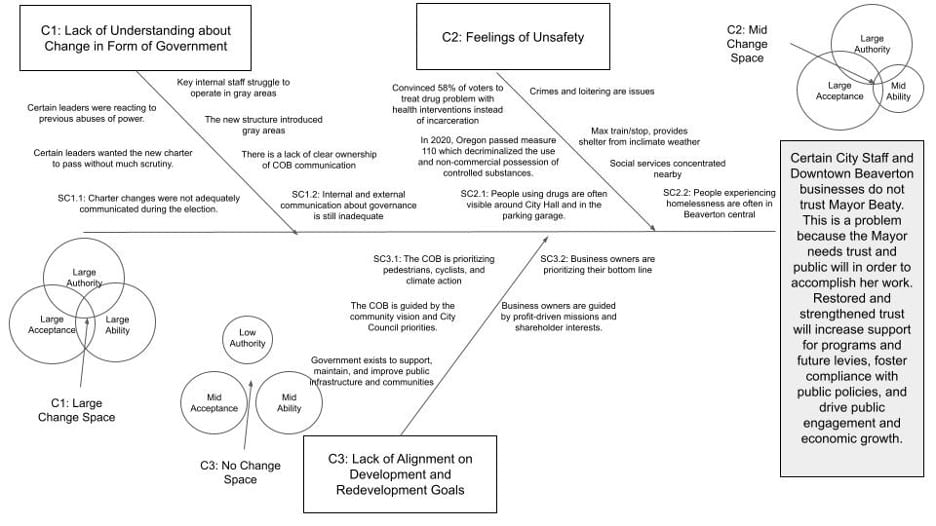

When we began, the identified problem was a lack of trust in local government. We were hearing lots of negative constituent input regarding the upcoming implementation of a state mandate to update our city code related to camping (homelessness). It seemed to me that communication was strained or lacking, and we had a trust issue. Communication was a necessary ingredient, but all the beautiful words in the world wouldn’t fix this.

As the course progressed, the problem evolved to be primarily about certain downtown business owners losing trust in city government. A further iteration revealed that as the chief political figure for the city, the Mayor was the target of the trust issue. The latest problem statement became: “Certain City Staff and Downtown Beaverton businesses do not trust Mayor Beaty. This is a problem because the Mayor needs trust and public will in order to accomplish her work. Restored and strengthened trust will increase support for programs and future levies, foster compliance with public policies, and drive public engagement and economic growth.”

The Mayor’s team each met with people one-on-one and in small groups to form and build relationships, learn about what’s important to them, and open pathways for future collaboration. We were reminded of how much people enjoy being together, and how sorely this was lacking during the pandemic. We witnessed how much people appreciate being included–whether that is an invitation to participate in an event, give a presentation, or be considered for a program. We were reminded how meaningful it can be to show up or reach out – even when we don’t have the solution or we don’t see eye-to-eye.

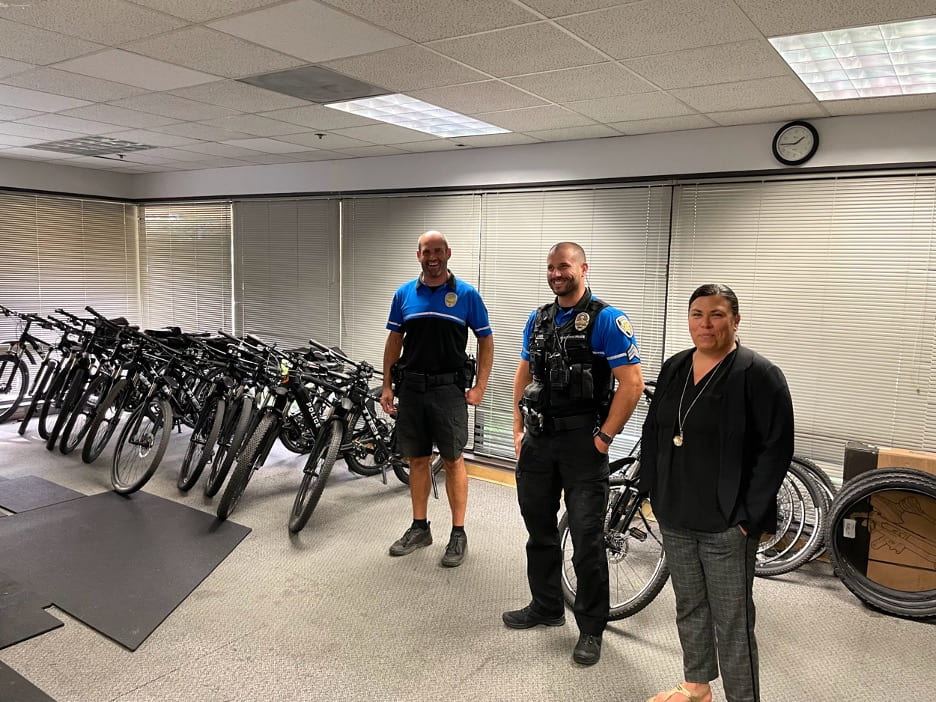

While one-on-one conversations persisted throughout, we shifted to include a variety of activities that could help to build trust. We visited various downtown businesses to chat with their owners, participated in a cleanup activity organized by business owners, and met with the team of bike officers who deal with concerns of the business community and homelessness. We organized three additional trust-building activities that included the Mayor and Council, staff, and community leaders. And we began to approach all of our work through a lens of building relationships and trust.

Trust was clearly the most pressing issue, but it was a struggle to pursue this work that is subjective and can’t be easily measured or quantified. Nevertheless, I can confidently affirm that this course helped us to take great strides toward building trust with key individuals and groups.

Of the many things I learned, here are a few that stand out:

- Don’t overthink it! This iterative process is messy and there’s not a “right” way to deconstruct your problem–no perfectionism allowed here. Just keep iterating, learning, and moving forward. It’s remarkable how much progress can be made in a few short months.

- Do Let It Go. Complex problems cannot be addressed through plan-and-control processes–there are too many unknowns. Instead, approach with curiosity and a growth mindset. Ask questions and seek to understand people and problems.

- Do Share. Reflecting and reporting on what we are learning and what new leads we are making is a great way for everyone (the team, the authorizers, the public) to get a sense of the progress that’s being made. What we are learning along the way, and the inroads we are making with others – these are the actual accomplishments.

- Do Express Appreciation. When people don’t feel appreciated, it can trigger negative emotions and result in a number of negative outcomes. To prevent this, we should practice listening deeply, identifying the merit of what someone is saying, and feeding that back to them so they know they are heard, understood, and respected.

- Do Lead with Your Heart. To build trust, you have to demonstrate both competence and empathy, reliability and positive intent. It’s not enough to solve problems–we have to do it with heart. People have to see and believe that we truly care.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. 47 Participants successfully completed this 7-month hybrid program in December 2023. These are their learning journey stories.