Guest blog by Anis Saidi, David Friedman, Diksha Kataria, Krista Gon, Lucy Kruske, Tatenda Mujeni, Younmi Kim

Complex problems are not impossible to solve. As we learned over the course of this module, PDIA teams must adopt a humble, progressive, and iterative approach to tackle complex problems successfully.

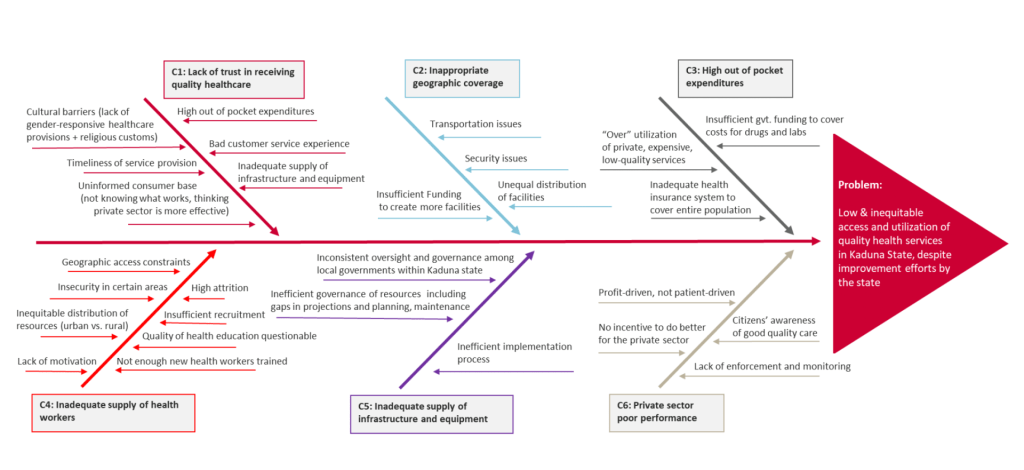

The initial step is deconstructing the problem into various causes and sub-causes. This provides clarity by identifying smaller, more manageable issues to address. Furthermore, teams should challenge preconceived assumptions and review the problem definition iteratively each week to glean gradual insights over time. In this vein, our PDIA team constantly tested our assumptions by reviewing empirical data, reports, research, and qualitative insights from stakeholders and local experts that challenged and enriched our existing understanding of the issues at hand.

Problem solving can be a lengthy and uncertain process. Moving progressively into the unknown, testing ideas through active iteration, learning from failures, and resolving small issues is a crucial step. The PDIA approach’s strength lies in its ability to implement short and rapid interventions that address multiple local challenges, culminating in a sustainable solution to complex problems.

Our team was highly diverse. We hailed from six different countries with six different native languages, and we had cultural differences and different professional backgrounds. Nonetheless, we found common ground in our passion for the project. As such, we cheered each other on, thanked each other, and aided one another in times of need. These acts of kindness fostered high morale among our team, and the diversity of our experiences and backgrounds gifted us with a rich learning experience.

Our Progress

When we were assigned our project topic, our team had very little contextual knowledge about the healthcare system in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Our sheer unfamiliarity with the initial problem statement – “Low utilization of quality health services in Nigeria” – was daunting. At the same time, it was this unfamiliarity that pushed us closer to the PDIA process and prevented us from taking the solutions-oriented approach we were accustomed to.

In our initial meetings, our authorizer, Dr. Amina Mohammed Baloni, shared with us that low utilization of quality health services in Kaduna State was a manifestation of several deeper challenges in the health system. These included insufficient numbers of health workforce, inadequate supply of health equipment, and poor regulation of private health facilities. Kaduna State’s Ministry of Health was well aware of these challenges, and our early conversations with key stakeholders showed that the state had in fact made serious attempts to address the aforementioned concerns. Through improved infrastructure and supply chain management, ensuring a primary healthcare facility in each ward, and redistribution of health workers, the public facilities were performing better than they had in previous years.

Despite these improvements by the state, patients were still not utilizing the public health facilities as expected. Patients often avoided primary health centers altogether and instead opted for care at private or higher level public facilities, where they perceived the quality of health services to be better. This perception was especially puzzling because, in practice, private health facilities were shown to provide inferior services. Why was there such mistrust among patients of public primary health services?

As we dug deeper, we discovered that low utilizations of quality health services was, in part, tied to the unavailability and poor attitudes of healthcare workers at public primary health facilities. Beyond this, though, poor private sector performance and other structural issues were also to blame. It was evident to us that the problem at hand extended far beyond just the primary care level and the public sector; it was only through iteration and continuous probing that we were able to identify this interconnectedness.

In light of these findings, we adapted our final problem statement to be: “low and inequitable access to quality health services in Kaduna State, despite improvement efforts by the state.” Our understanding of the problem only grew deeper throughout the problem construction phase, and we continued to uncover more about the problem throughout the six week process.

Words of wisdom

In the very first lecture of this module, Matt and Salimah raised the importance of humility throughout the PDIA process. Specifically, we were told that we were not expected to solve the issue, nor were we the experts in the room – we were here to learn the PDIA process and provide a new perspective to our authorizer. In acknowledging our limitations and contrasting this with our authorizer’s expertise, our team felt little pressure to quickly propose solutions, which allowed us to fully lean into the problem deconstruction aspect of PDIA. Knowing that we had much to learn made us eager to dig deeper into each problem, and we encourage anyone participating in PDIA to similarly start from a place of humility.

Early on in the course, Matt also advised our teams “not to let perfect be the enemy of good.” Indeed, In many of our initial team meetings, our team spent significant time wordsmithing the phrasing of our problem statement, or peeling back another minute layer of the problem. We quickly realized that it was not only cumbersome, but also unrealistic to expect that we would get a perfect result on our first pass at analyzing an issue. Over the course of the module, our team became much more comfortable accepting “good enough” and moving onto other important parts of the project, knowing that we would be able to revisit these problems, iterate them, and delve deeper into the issue without sacrificing precious time and quality. We strongly encourage other students and practitioners participating in the PDIA process to lean into this learning and be comfortable with good enough.

Our team also realized just how important “psychological safety” is to creativity and teamwork. Matt and Salimah emphasized psychological safety as a way to encourage all members to participate and express their ideas freely, so that individual creativity can contribute to the group learning. Having a group norm that ensures every member has a chance to speak has helped us to have faith that other members will listen to us. Also, the acts of kindness, check-ins, and appreciation we gave one another established a comfortable team dynamic, allowing freer discussions. When working as a team, it can

be tempting to focus on getting the job done – even at the expense of inter-team relationships. However, our team saw that if we build trust within the team through rigorous norms and inclusive practices, our cohesion will be reflected in our superior work.

Finally, small steps can result in a big change. Oftentimes, policymakers think that they need to propose comprehensive reforms to solve complicated issues. However, when implementing these “perfect policies”, the unexpected challenges of the real world often lead to unexpected outcomes and sometimes to failures, leaving policy makers disappointed and discouraged to solve problems. PDIA showed our team that starting with small steps and iterative processes can solve complex problems that seem large. Failures are welcome for further learning. By viewing big problems as something that can be explored step by step, as PDIA encourages, we can overcome this tendency and move toward a large change, incrementally.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2023. These are their learning journey stories.