Guest blog by Soraya Mohideen, Shunta Takino, Michaela Tobin, Akinobu Toyoda, Andres Valenciano

Writing a team constitution seemed like a tedious step, but it was vital and something that we recognized as beneficial in other contexts. The process of developing a constitution got every team member to think about what a well-functioning and effective team looked like and to share this with one another. This allowed everyone in the team to understand each other’s priorities and motivations from the beginning and ensured alignment across the team.

Closely linked to this is the value of psychological safety. It was empowering for all of us to feel that we could open up and share frank opinions about both the topic we were working on and how the team was functioning. Far from weakening the team, this served to strengthen the team, as any concerns that a team member had would be discussed and addressed instead of remaining under the surface but nonetheless lurking. This rested on our mutual understanding that any critiques or disagreements were not personal, but rather in our joint commitment to tackle the problem. Too often, we are afraid to critique others’ points or perspectives, only to have regret later when it ends up being that the point you could have made would have been useful.

The PDIA process presents a contrast to the emphasis on solutions in traditional policy-making. This was highlighted in conversations with stakeholders, as we found they were always keen to speak of the solutions and programs they were implementing, but not necessarily sure what problem they were trying to address. The framework provided the team with an appreciation for the value of deconstructing the problem rather than jumping to solutions or modalities. Coming from a more familiar theory-of-change and solutions-based approach to development, it was difficult to not conceptualize the problem in terms of potential solutions. At times it was uncomfortable to move towards an end result without knowing what that result would be. We were made to trust the process and frequently reminded ourselves to not look too far ahead.

When we first heard of our team’s problem, it seemed difficult to solve because it was complicated, ambiguous and multidimensional. However, following the PDIA approach and incorporating feedback in our iterations, we understood the problem and potential approaches better over a short period of time. Our assumptions changed frequently. We found early on that one should not get attached to any one definition of the problem because it could change with the input of new information. When doing this type of work, one must be flexible and accept that what one thinks is the answer one day may not in fact be the answer the next.

It was difficult to not conceptualize the problem in terms of potential solutions. At times it was uncomfortable to move towards an end result without knowing what that result would be. We were made to trust the process and frequently reminded ourselves to not look too far ahead.

The progress we made

There was a lot of ambiguity around the challenges that Bogotá was facing and how our team would work to address them in the early weeks.

Our conceptualization of the problem changed drastically from Week 1 to Week 7. Our topic was introduced to us “Artificial intelligence for the labor market in Bogotá”, as our authorizer was currently exploring AI tools to address labor market challenges. We soon found that AI was our authorizer’s solution to the problem and not the problem itself, and so, in keeping in line with the PDIA methodology, we chose to not let this fact cloud our analysis.

Similarly, in early conversations with our authorizer, the problem was defined as a high unemployment rate. However, as we dug into the problem through stakeholder conversations and our own independent research, we found that the problem was much more nuanced. We realized that a high unemployment rate was more of a symptom of the problem.

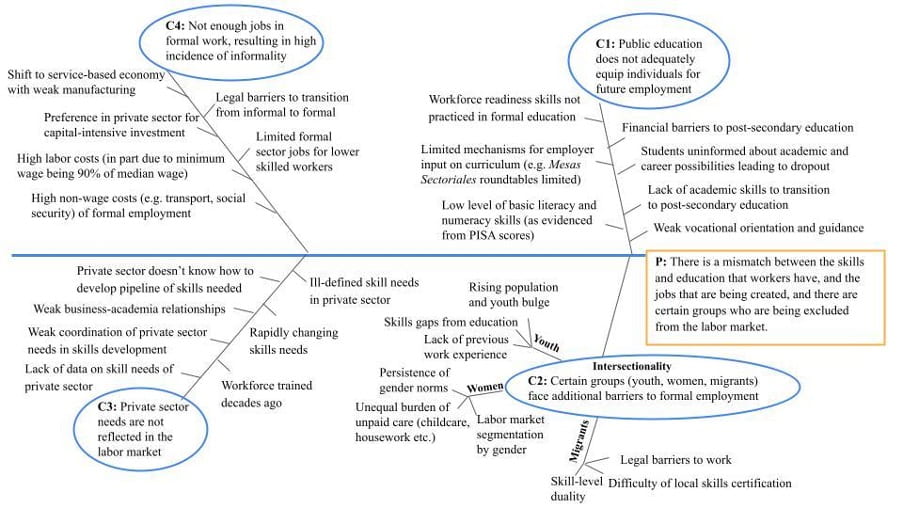

We identified the problem as being more closely related to skills mismatch in the labor force and specific barriers to entry for certain groups of people, namely women, youth, and migrants. In deconstructing the problem, we found that there were several sub-problems within various facets of society, such as the education sector, the public sector, or social services, which collectively contributed to Bogotá’s labor market challenges.

With each stakeholder we spoke to, our understanding of the problem evolved and we were frequently going back to change our fishbone diagram and even our definition of the problem statement:

- We used conversations with individuals outside of Bogotá and not directly working on the problem to deepen our understanding of challenges facing certain groups (youth, women) in the Latin American region and to provide learnings on macro-level trends.

- In speaking with agencies such as the Bogotá Innovation Lab, the District Agency for Higher Education, Science and Technology, and the Secretariat of Economic Development, we learned that the municipal government has been innovative in their approach to addressing the problem and are already implementing several programs to improve labor market participation. In speaking with these agencies, we were able to explore different perspectives on the problem, such as from those who work in youth education or with more knowledge of the private sector. We decided to leverage these initiatives when looking for entry points.

While our view of the problem had become much clearer, it was still difficult to see how our authorizer could address a pervasive problem that seemed too large to be adequately tackled by the municipal government. The AAA analysis allowed us to examine our authorizer’s levels of authority, acceptance, and ability to address each of the sub-problems that we had identified in our final fishbone. We thus had a better idea of the change space and where we could begin to iterate. In our ideas for iteration, we focused on building a more reliable and accurate evidence base that our authorizer could use to better inform current and future policies and programs targeted at labor market challenges.

Words of wisdom

We encourage teams to embed psychological safety in their team, as it is foundational to working through complex problems, and allows everyone to openly express their ideas and thoughts. It is thus essential to prioritize group dynamics just as much as you prioritize your own learning about the problem.

We recommend that teams not only think about how they wish their team to work when drafting the constitution, but also how to ensure that joint commitments are translated into reality. In our case, as the team constitution was a living document, we later added mechanisms that would ensure our team worked how we all hoped it would. In hindsight, having these embedded in the team constitution from the beginning would have aided the functioning of the team.

We encourage anyone participating in the PDIA process to embrace the principles underpinning the process, even if they find the process uncomfortable and progress may feel slow from time to time. Most importantly, we encourage students and practitioners to avoid jumping to solutions, and instead, focus on deconstructing and deepening understanding of the problem.

This requires deep curiosity to understand the problem and continue asking questions and gathering data. This was important for our team as there was a risk of embedding a technology or AI-based solution into our understanding of the problem. Our definition of the problem opened our eyes to different ways of seeing and addressing the problem. Trusting the PDIA process will allow your team to have clarity on what steps will help you to make progress, and to eventually come up with ideas that are informed by the local context and begin to address the problem you identify.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2023. These are their learning journey stories.