Guest blog by Adolfo Rubinstein, IPP ’22

Having been minister of health of my country during the previous administration (2017-2019), I felt fairly confident in my own policy-making abilities but, at the same time, I realized that policymaking is not an abstraction. It should get to policy implementation and hopefully policy impact. However, as we learned through the IPP program journey, policy formulation, even policy adoption, can be very far from policy implementation and policy change. Even to have the support of the president himself, the top “authorizer”, is not enough to move forward some of the policies, as I painfully experienced as minister, where very good ideas thought and planned were lost in translation when facing the different stakeholders and agents involved in the implementation process. This existent and difficult-to-overcome gap, made me think that perhaps what I needed most was to learn a different approach for implementing public policies. I then talked to Michael Reich, an outstanding health political scientist from Harvard T Chan School of Public Health, who is my “policy” mentor and was my advisor during my term at the office. Together, we identified the IPP at HKS as the best option. He contacted Matt and later Matt and I had a call to talk about the IPP program. After that call, I was convinced that this was the program I badly needed, and made the decision to apply to the IPP program.

I am now chairing the health commission of the opposition, which is composed by participants from the four parties of the coalition. Our commission has been appointed by the coalition leadership to build the health strategy and the roadmap should the coalition wins the next election in mid-2023, which is highly likely nowadays. One of my aims with this group of health experts along this year was to identify together the main problems of our health system in order to get them involved in a “PDIA like” process to find possible solutions that could be implemented. We decided to start with the PDIA exercise, focused on one of the problems, that would be my policy challenge for the IPP program. Then, we could use PDIA as a model to replicate with other policies and problems we will have to deal with.

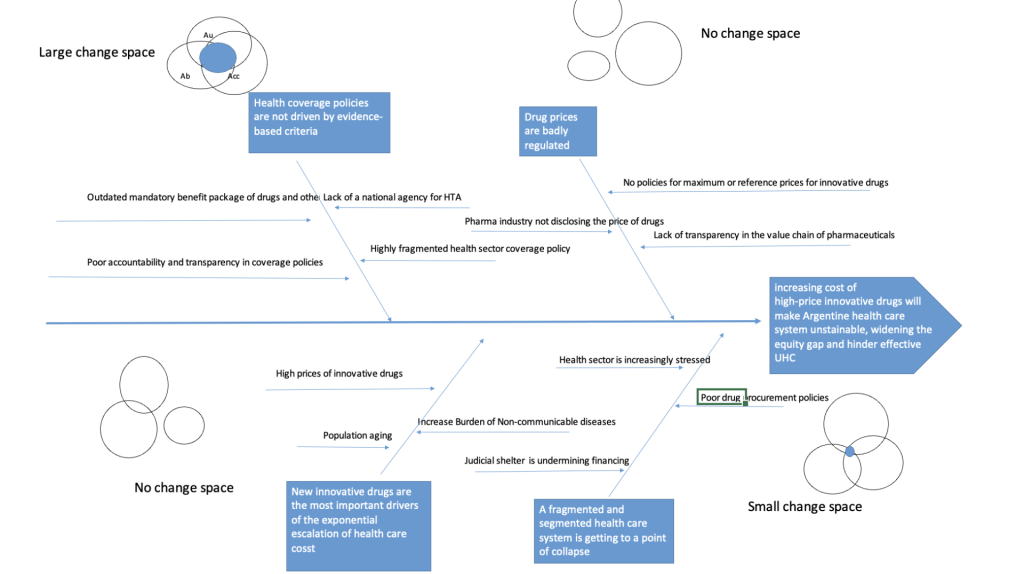

In my policy challenge, we stated the problem as “Increasing cost of high-price innovative drugs will make Argentine health care system unsustainable, widening the equity gap and hinder the achievement of an effective Universal Health Coverage (UHC)”. Almost 10% of Argentine GDP is spent on healthcare, one of the highest in Latin America, with sub-optimal results according to that expenditure and increasing health disparities among districts, SES level and type of health coverage. The exponential increase in high-priced medicines (nearly 30% of its health spending), will make the system unviable in the next few years. Currently, there is a weak response to this major problem. Despite the existence of an explicit package of health benefits coverage, this is outdated, discretionary, and mandatory only for some social and private health insurances. Even though there is a national commission to evaluate the inclusion of new technologies into benefit packages, their recommendations are not binding. Moreover, drug prices are poorly regulated and prices and coverage policies are different and fragmented among the different health sub-sectors in Argentina (public, social security and private).

What about the stakeholders involved in this matter? In addition to the government (ministries of health, finances and labor), and the national legislators, other important agents have a say. Among them, are the provinces (Argentina is a federal country), the trade unions (most of social health insurances are run by them), the private sector (financers and providers), the pharmaceutical industry (multinational and national companies), the media, the consumer associations and the public at large of course. All are or might be influential players if they support or oppose to the changes.

Therefore, with all these issues in mind, I started the PDIA journey with my team. After coming back from Cambridge, I reframed my problem statement and shared my fishbone diagram with my colleagues to make sure I was addressing most of the relevant root causes and sub-causes in each bone. Solving this policy challenge would require multiple interventions, which would need multiple entry points for change. For each root cause, we built a Venn diagram intersecting Authority, Acceptance and Ability to explore where we should act first, depending on the space of change. In this regard, the deconstruction and sequencing of a problem made us take better decisions on the timing and staging of the engagement, given the contextual opportunities and constraints in each root cause.

Of course, things were not that easy. As we moved along the different iterations, I learned to take into account some aspects that I had overlooked, mainly my misperception about things that were “obvious” for me and therefore taken for granted but were not so obvious to some participants. So that, I started to work consciously on the first P of Rob Wilkinson’s 4P model of leadership, aiming to come to a shared perception on the importance of the policy challenge, the problem and its determinants. This common understanding would be key to advance to the following iterations and get more legitimacy from my peers. Another tip that I took from Rob´s podcast on process, was to actively exert “self-silencing”, trying to avoid some biases in group thinking such as looking for artificial consensus or herd behavior. Fortunately, at the end of the last iteration, everyone felt that we had had a small but a tangible progress, and the consensus, as a product of negotiations, had been fruitful. One of the most important things I learned was that in order to build a document that reflected a high level of consensus reached among people coming from different positions, “everyone has to give “. And this is what I had to do, no matter I got a bit disappointed when some important things to me were not taken into account by the rest of the committee.

Finally yet importantly, I think I had two different challenges along the way. The first one was to get consensus with the other members of the health commission on the policy challenge, and then advance through the different iterations. The second challenge (for me) was how to adapt our group interactions to a PDIA format since we were building the health plan and the implementation roadmap but were not actually implementing our strategy. That would occur in a further stage if we would win the presidential election next year, which as I said, it is very likely but obviously is not certain. Nevertheless, admitting that we work in a kind of “pre-implementation stage”, I decided to use the tools given by the PDIA, instead of engaging with the traditional “Planning and control framework”, which would have been probably easier to do but most likely would turn to be wrong, considering the lot of unknowns in my policy challenge .

After this so productive learning journey, I think that I got what I was looking for. Now, I understand the complexity of implementation processes when you are committed to a public policy change. Moreover, I am using these theories of change, frameworks and models to help implement other policy challenges. For example, I am using PDIA with health authorities and bureaucrats of the ministry of health and the social security bank in Uruguay to help develop a national integrated health service delivery network for care of rare diseases.

Here are my final recommendations for policy makers and practitioners who are engaging in public policy implementation: try to use the PDIA toolkit whenever possible. Iterate, learn, build authority and adapt to the specific context your policy will take place in to get better functionality and legitimacy, and therefore increase the chances of policy change and real impact. In the end, as Matt Andrews wisely says: Implementation is about people and relationships.

I am grateful to my professors and colleagues for this so fantastic experience!

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2022. These are their learning journey stories.