written by Salimah Samji

Over the past three years, we have engaged on research titled “Understanding How Education Systems Build Capability, Innovate and Improve their Practices” as part of the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme.

One of the components of this work is to explore whether BSC’s Problem Driven Iteration Adaptation (PDIA) approach to build capability by delivering results can be customized for use in the education sector. As part of this work, we have published new papers, written retrospective case studies (South Africa and Brazil), recorded podcasts, and reviewed the work of development practitioners who have taken our online course and applied PDIA in the context of education. This blog draws some initial insights from the experience of our online course participants.

PDIA and Education

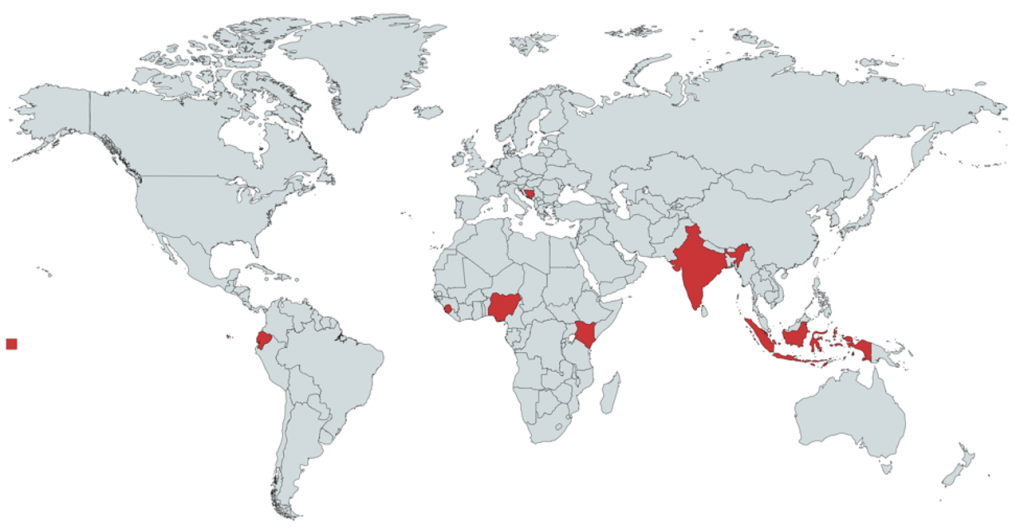

In the period between March 2017 and June 2019, fifty-six development practitioners, working in thirteen groups, across seven countries, nominated problems related to the education sector to work on in our 15-week Practice of PDIA online course. These practitioners worked for:

- 2 Country governments (48%)

- 4 NGOs/Think Tanks (25%)

- 3 Consulting firms (27%)

About half of the groups were homogenous, with seven out of the thirteen groups made up of members from the same organization, while the six were comprised of members from multiple organizations (government, think tank, consultants) working together on the same problem.

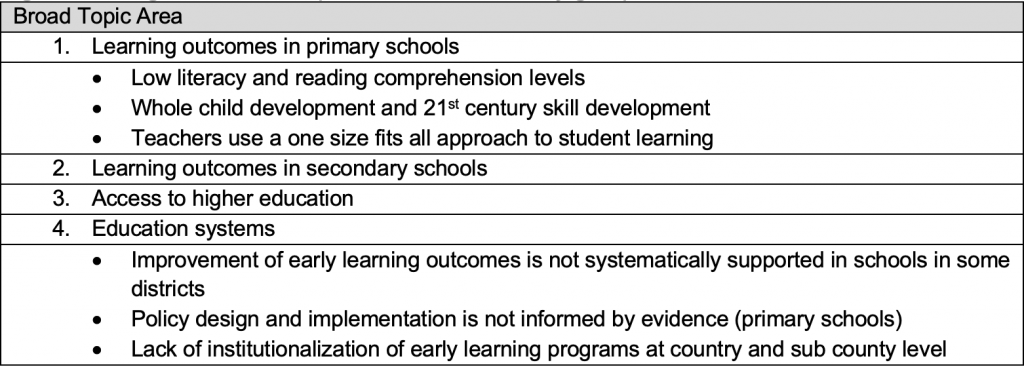

Of the thirteen groups, seven selected problems related to learning outcomes in primary schools, four selected problems related to education systems, one selecting problems related to secondary education, and one selecting a problem relating to higher education. The topic areas covered in problems identified by the various groups are summarized below.

Insights and Observations

All thirteen groups found the PDIA approach useful in their work. A key learning for many of the participants was that the problem solving process does not follow a linear or predictable path. One participant noted, “we have to be ready to face failures, to look back at what we have done, to adapt or redesign what we have planned and be brave and consistent enough to keep trying.”

Many participants also noted the importance of the local context. One noted, “Problems need to be recognized as being locally relevant, and solutions must be seen to be productive to local stakeholders.”

Some participants from consulting firms noted:

“Through this course even more than before, we have become aware that local embedded-ness is crucial.

Wicked hard problems should be driven by local teams, not external development projects. The latter can only catalyze and support complex change processes, but ultimately these have to be driven by local actors.

Always work in partnership with your target groups, listen and speak their languages.”

Here are some of the key lessons they learned, organized by PDIA concepts and tools.

PDIA: Problem Construction and Deconstruction

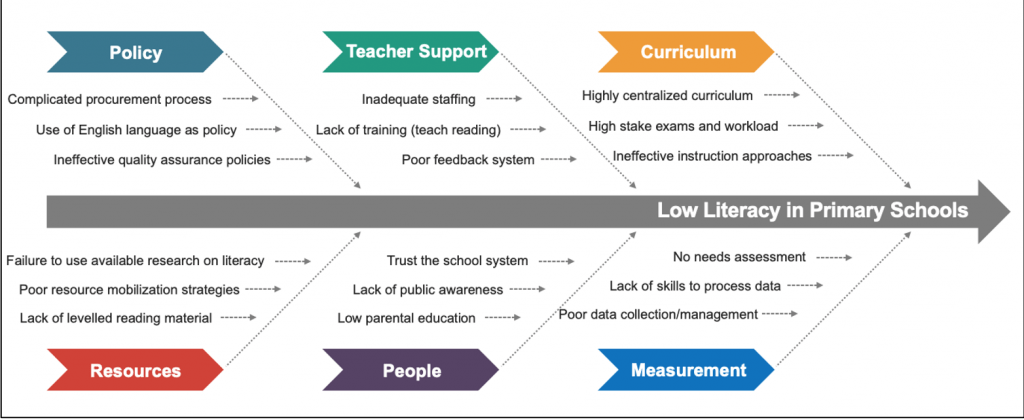

The first two steps in the PDIA process are problem construction and deconstruction. In problem construction, one explores why a problem matters, to whom it matters, who needs to care and what the problem would look like if it were solved. The problem deconstruction uses the 5-why and Ishikawa or fishbone diagram to break down a problem into its root causes.

All participants, regardless of the type of organization they worked for, found this process extremely useful and relevant. A key takeaway from the problem construction process was the realization that development practitioners often confuse selling solutions with solving problems. One participant noted, “avoid the trap of formulating the lack of a solution as the problem.”

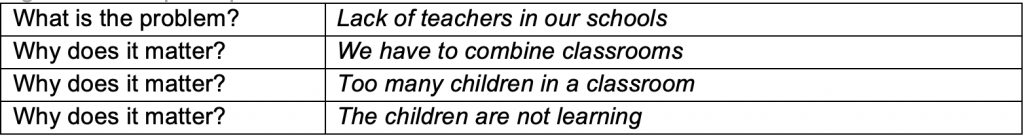

The figure below illustrates framing a problem as the lack of a solution. In this example, the problem is that children are not learning, while the lack of teachers might be one of many possible solutions to this problem. The process of problem construction helps to provide clarity on the problem statement.

Participants also realized that there was often a bias toward quickly jumping to solutions, without clearly identifying or understanding the problem first. This has led to interventions that did not address the root causes and therefore did not help resolve the problem. They noted, “ask all the whys before you design the solution.”

Building on the example from above, if participants started with the problem of the lack of teachers, they would then figure out strategies to hire more teachers. However, it is unclear whether more teachers would lead to improved learning outcomes. What were the causes of children not learning? was it teacher training? curriculum? availability of books and reading material? language of instruction? There could be a variety of reasons why the children are not learning and each cause would require different interventions. This is the reason why the problem diagnosis part of PDIA is so critical.

The key takeaway for the problem deconstruction process was the importance of having a clear problem statement and then breaking it down into smaller pieces to find entry points. They noted:

“It doesn’t matter how clear my understanding of the problem is; it matters how clear our understanding of the problem is: and perhaps that means my perspective on the problem needs to shift.

I learnt that what my team identified as a problem became a step 2 problem and the primary problem was something we had not thought about before.

The five whys and fishbone analyses reveal root causes and deeper problems – those that don’t assume the answer.

You really need to see through the current situation to see what is the problem, and where is the root of the problem that needs to be solved.”

The process helped them realize that different stakeholders bring different perspectives thus allowing for a more robust deconstruction of the problem. Visualizing the problem in a fishbone diagram highlighted the complexity and interconnectedness of their problem. One of them noted, “constructing and deconstructing the problem is as important as solving the problem.”

The figure below is an example of a fishbone diagram drawn by participants in the course focused on the problem of low literacy in primary schools.

PDIA: Building and Maintaining Authorization

Authorizing environments are commonly fragmented, and difficult to navigate. Programs and policies typically cross over multiple authority domains in which many different agents and processes act to constrain or support behavior. Whether formal or informal, authority structures are often inconsistent. This means that one is never guaranteed continued support from any authorizer and therefore authority needs to be treated as a variable and not as something fixed.

Most participants appreciated learning more about how to identify and map various authorization needs, how authority is structured in their context, and how to grow their authorization over time. They noted:

“The idea of understanding one’s stakeholder environment as the source of opportunity and constraints in resolving the problem —particularly the idea of the multiple layers of an authorizing environment (horizontal mid-level, bottom level, as well as the vertical levels), thereby providing the keys to the relevant problem framing and to its/their solution.

Understanding our authorizing environment is crucial. Without it, we are unlikely able to drive any changes.

I was skeptical about involving government in my current work as they often give hassles rather than support. But then, considering how important their role is in doing the reform and creating an authorizing environment, I realized that I need to keep involving and updating them about the progress that we have made with their people in order to influence them to authorize us in undertaking any initiatives to do the reform.

I learnt that the authorizing environment is critical, and that managing the authorizing environment effectively draws in the necessary support for the problem.”

PDIA: Iteration, Small Steps, and the Power of Reflection

Iteration is a key step in the PDIA process, whereby ideas are identified and put into action with tight feedback loops. The small steps help to flush out (or clarify) contextual challenges, allow local legitimate solutions to emerge, and fosters adaptation to the local context. This is especially important in uncertain and complex contexts where reformers are unsure of what the problems and solutions actually are and often lack confidence in their abilities to make things better.

In PDIA, there is no separation between the design and the implementation phase of solving complex problems. This is a simultaneous process that occurs via embedding experiential learning (or “action learning”) into the iteration process.

In the PDIA course, participants had the opportunity to undertake two iterations, allowing them to learn how the process works in practice. One group of participants who were working on the problem of low literacy decided to take some action on a sub-cause in their fishbone diagram around inadequate public awareness. Their idea for the first iteration was to develop narratives for public conversation to be positioned in the arts pages of the print media and for discussions in the broadcast media. They also wanted to negotiate for free editorial space in at least one leading newspaper with nationwide circulation.

Over the period of a week, they wrote some stories and articles but soon learned that they needed the approval of the Director of Policy and Planning at the Ministry of Education (MoE) before they could publish them. When the participants reflected on their first iteration in their check-in they realized that they needed to bring in their authorizers as co-owners of this work, otherwise they risked rejection of their proposals. This allowed them to adapt their idea in their second iteration.

Another participant group working on the problem of low learning outcomes in secondary schools decided to request access to examination results data to better understand patterns and to identify if there were any positive deviant schools. At the end of the week they learned that they did not have sufficient authorization from the relevant senior official in the Ministry to get the data.

When the participants reflected on this in their check-in they realized that they needed to build some authority. In their second iteration, they were successful in getting the data. However, they found that the data was at a higher level of aggregation (school rather than individual) and used a different indicator. They also learned that the Ministry did not assign IDs to secondary schools which prevented them from reconciling data within different departments of the MoE. These lessons were important for the team as they were able to learn quickly and adapt their next steps accordingly.

Both these examples illustrate how the process of iteration fosters rapid learning and adaptation to the local context.

All participants found the iteration process particularly useful. They noted:

“Learning is something embedded in a core implementation team and NOT isolated in a different set of ‘Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning’ activities.

Change can take place in small iterative steps and we don’t necessarily need to have the entire strategy mapped out in advance.

Do one small step at a time and then reflect on that to improve next steps.

The very frequent reflection of action together as a team is vital to the insightful and disciplined development of a solution.

By documenting the small progress we made and reflect that will give a sense of achievement. That will keep me motivated and committed to reach the goal.

Learning from iteration: The most constant thing is that new things are emerging all the time. The whole iteration exercise is a kind of continuous ‘epiphany,’ with a series of ‘eureka’ moments.”

PDIA: Working in Collaborative Teams

Solving complex problems requires working in teams. However, working collaboratively is neither obvious nor innate. It is a yet another muscle that needs to be built.

In the PDIA course, participants register as a team to work together on a problem that they nominate. Most participants appreciated learning how to make teaming work. They noted:

“I think that it is very important to have a team committed to the propulsion of fast moving activity; and that the very frequent reflection of action together is vital to the insightful and disciplined development of a solution.

Leadership and group dynamics matter – that it’s okay for people to take different roles within the group, but that leadership can be shared, diffused.

Allowing the team to respond to the iteration check-in questions is an important step of owning the process. It also gives them an immense sense of achievement.

It is vital that one is working with/engages an appropriate group of people. This group needs to include people who can play substantive, procedural and maintenance functions; but is also needs to be organised into small enough units, so that each unit is able to work as a team and interact constructively.

The PDIA process is designed to help a team iteratively solve problems as they learn about the capabilities they lack and need to actively develop and to expand their legitimacy.”

Summary

PDIA offers a process and framework for development practitioners to solve complex problems. The hallmark of the PDIA online course includes the practical/experiential nature of the course, the length of the course which allows for the spacing effect of learning in one’s own context, and teaching teams working together to create sustainable change. Through a process of learning by doing, participants experience how creativity can emerge in the face of complexity.

It is therefore not surprising that many of the lessons learned by practitioners working in the education sector echo those we have seen in other sectors as well. These include:

- Problems are often framed as the lack of a solution.

- There is a bias toward jumping to solutions before fully diagnosing the problem.

- Breaking complex problems into smaller pieces helps to find entry points.

- Different stakeholders bring different perspectives thus allowing for a more robust deconstruction of the problem.

- The process of iteration fosters rapid learning and adaptation to the local context, allowing solutions to emerge.

- Local ownership and buy-in from stakeholders is key. Participants from a consulting firm noted, “Wicked hard problems should be driven by local teams, not external development projects. The latter can only catalyze and support complex change processes, but ultimately these have to be driven by local actors.”

- Building and maintaining the authorizing environment helps to draw in the necessary support for the problem.

- Big change starts with small steps.

It is important to note that the PDIA approach is most useful for solving complex problems where there are a large number of unknowns and there is a need to learn about the context. There are various other approaches that can be used for simple or logistical problems where there are few unknowns.

While the course only has two iterations built in, our engagements with country governments are usually much longer. Teams we directly work with, conduct a series of rapid iterations with constant learning, action, and adaptation over a period of 6 months to a year. During this time period, teams find that they build capabilities, solutions emerge through the process, and they move toward becoming a learning organization.

PDIA is not conceptual. The only way to learn it is by doing it.

For more details, see The PDIA Toolkit.