Guest blog written by Judy Farvolden

I am passionate about vibrant, equitable, sustainable urban life. My journey began in Paris when, as a 17-year-old living for a year in the City of Light, I wondered at the difference between living in a place where every day-to-day thing I needed was on my own block and my familiar and comfortable North American suburban life. I decided that the difference was the extensive subway system that made it possible for me to get anywhere in the city in 30 minutes, cheaply and safely, even as a teenage girl. That led me to study transportation engineering, and in particular systems design, because I believed the answer was to be found in mathematically optimizing transportation networks.

In the 30 years I’ve lived in Toronto, Canada I’ve watched the city grow from – not much – into North America’s fourth largest and fastest growing metropolitan region, with North America’s worst traffic congestion. About 10 years ago, after three engineering degrees and two decades in network optimization and mathematical finance, I realized that more math was not the “answer” to our transportation problems, and the real problem must be getting it done in policy. I decided to see if I could come back around and contribute to addressing the issues that had so motivated me but that I’d never actually engaged in.

I found that opportunity at the University of Toronto where, earlier this year, our proposed Mobility Lab was designated an Institutional Strategic Initiative and granted three years of seed funding on the promise that it would create a multidisciplinary network of researchers that would drive innovation in urban policy, thereby addressing the global challenge for cities to evolve into more sustainable, equitable, and resilient urban forms and mobility systems. The question was, how?

It seemed simple enough when I got the ISI Implementation Manual. We were to hold a strategic planning session and report annual progress against key performance indicators. We would deliver, as promised, by training students, delivering research results, engaging with the public and providing evidence in support of decision making. Yes, but how?

The first useful IPP lesson learned was that, like Lewis and Clark, we do not know where we are going or how long it is going to take to get there. I also realized that it would take longer than three years to deliver on the promise we made to our funders, but we must show progress to keep the money flowing. That told me that we needed a plan that builds on the dimensions of functionality, how we have an impact, and legitimacy, how we build – and keep – support for what we are doing. The question was still, how?

Over the course of several weeks, I iterated on a plan with my supervisor that we would present for discussion to the Mobility Lab Leadership Team. The draft plan was intended to provoke an exchange of ideas but was in fact a “communication that does not motivate action”. It flopped, not least because few of them read the document before the meeting, though that didn’t stop them from having opinions!

This takes place in the context of a highly ranked public research university that is providing “start-up funds” to develop interdisciplinary research that addresses global challenges. But it has a hard-coded organization structure that makes interdisciplinary collaboration challenging and a reward system based on the classic pillars of research, teaching and service.

The leadership team, though passionately committed to the idea, balked at the thought of taking on yet more work. The expectation in the university is that every activity is headed by a professor, so that posed a challenge. They wondered if we could simply rebrand things we were already doing, rather than do anything new, which I knew that wouldn’t satisfy our funders. They questioned and challenged everything.

I realized I had a problem, but luckily, the very next week, PDIA had a fix for it – deconstructing the problem! It was uncanny how many times over the course of IPP that when I was stuck on something, IPP gave me an idea of how to work through it.

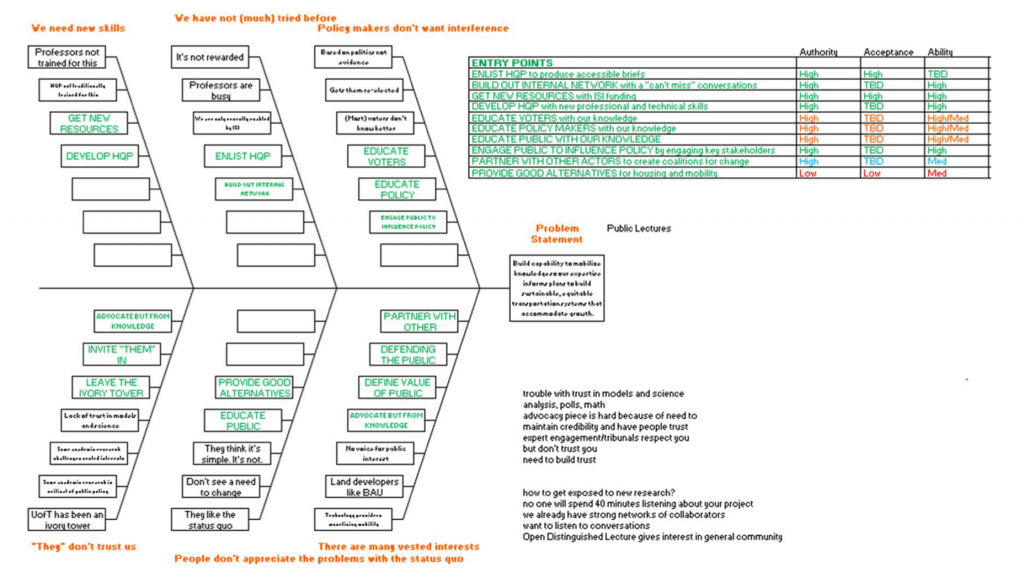

Deconstructing the problem, and asking why it was a problem, completely changed the way I thought about solving it. I realized that the highly aspirational language we used to secure funding didn’t describe a problem but rather, that the Mobility Lab was a solution, not the problem. I came to think of the University of Toronto as “the state” and we are building the capability to have social impact. I proposed that the problem was to address “What stops us from mobilizing our knowledge so our expertise informs plans to build sustainable, equitable transportation systems that accommodate growth”?

The deconstruction taught me some reasons were internal; we hadn’t really tried before because it’s not rewarded and we don’t have the bandwidth, and we don’t necessarily have the skills to do it. There were also external reasons, like vested interests and people who like the status quo, that policies tend to be based on politics, not evidence, policy makers don’t want interference and, generally, “they” don’t trust us. Drilling deeper into each of these problems led me to identify entry points and the Triple A exercise showed me I had a much larger change space than I first thought.

All of this led me to re-think my own leadership role. I realized I could be the leader of this initiative and mobilize and enable others to come along with me. I didn’t need to consult about everything if I kept my supervisor and the other members of the Leadership Team informed.

I became excited by the idea of exploring and developing the capability of our graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and research associates as mobilizers of knowledge and confident that, based on previous leadership experience, I could to it. I presented it as a win-win-win – we begin to address the bandwidth problem of mobilizing knowledge, our students acquire new skills and enhance their professional reputations, and we don’t impose on busy professors. I won that round handily.

Answering “why” also told me that if we want to matter, we need to step outside of our comfort zone in the traditional Ivory Tower. We are waiting to be asked for our opinions rather than putting them out there. We may want to be respected for knowledgeable opinions and hesitate to be labelled as advocates, but someone has to advocate for the public good. I realized we need to learn how to advocate, but from a position of knowledge, and to stop waiting to be asked for an opinion.

I began to engage with many different people, and I started listening, using my fishbone diagram as a prop to guide the conversation. In each meeting, I presented it as a collection of “our thoughts to date”, invited their comments and asked them to share their ideas on what the problem is, why the problem matters, and what we should do about it. I hoped by doing this that they would each see something of their ideas in the next version of the plan, realize that the other ideas came from colleagues whose opinions they respect, and that everyone would feel they owned the plan.

The first takeaway, for me, was that people like to be asked for their opinions. The second was that this approach really works! The ideas we had for our “entry points” got better with each meeting, and my confidence that the leadership team would buy into the plan grew. I started reaching out to people outside of our team and I will keep reaching out. This also led me to realize that the Mobility Lab itself would be more successful if it did not “push” information at people but became a “place” that used inquiry to engage people in a conversation about what they think the problems and opportunities are for sustainable, equitable mobility.

This was a first round in building legitimacy, in this case my legitimacy, as the leader of this initiative. It’s taken longer than I thought, but it has been worthwhile. I have scheduled a meeting to review the new plan (which does not include a strategic planning process) and I am confident that, this time, there will be buy in. With that settled, I am ready to launch the first of our entry points for action and I’m excited to see how the action learning phase goes. I am confident we are going to build our capabilities and our authorization to play in this space.

Despite my passion for the subject, when I began IPP I thought I was working on a challenge that was somewhat removed from me, but I learned that the challenge I was working on was a lot about myself which, over the course of IPP, led me to remember that I am the leader who can make this happen.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2021. These are their learning journey stories.