Guest blog written by Kanan Dubal, Jess Redmond, Ankita Panda, Arba Murati

No amount of information or research can and did prepare us for the intensity and unlearning that the Problem Driven Iterative Approach (PDIA) process demands. Theoretically, we knew what the PDIA process was, but the course facilitated an opportunity to learn, implement and receive constant feedback on the application of PDIA to a real policy case.

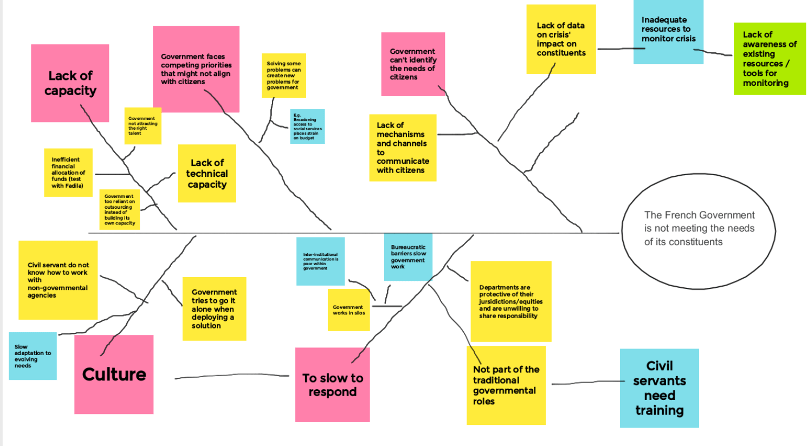

PDIA provides a blueprint to follow, but it’s not that straightforward. Each time we thought we had defined the problem and then deconstructed it, a new conversation or reading would spark a new idea, and new way of thinking about the problem leading to many versions of a problem definition. The deconstruction of the problem using the ‘fishbone’ approach helped us dive deeper into the problem whilst breaking a big issue down into smaller problems.

We had to constantly and consciously be aware that all ideas should be held as a possible option, and that nothing should be set in stone. PDIA encourages you to learn quickly and thickly rather than knowing and planning for ‘everything about the problem including the solution’. This requires constant iteration at all points and a willingness to adapt quickly if things are not working out at any step. This helps in identifying red flags before a substantial amount of time and resources are spent on a particular ‘solution’. We found the iteration process the most helpful when we were struggling to come up with good entry points with smaller, achievable goals. Iteration helped us get to a different level of specificity in the fishbone and problem deconstruction.

Our biggest unlearning as policy professionals was to ‘seek to fall in love with the problem, rather than the solution’. The PDIA process expects an ‘action learning’ agenda rather than the command-and-control route of ‘design, implement, evaluate’ which policy and development professionals tend to gravitate towards. Unsurprisingly, often we found ourselves drifting to this mode of planning extensive roadmaps and predetermined solutions, especially when it came to seeking entry levels and action points.

Working with French Prime Minister’s Office

The importance of iteration was clear in our applied work in the PDIA course. Our client for the PDIA course was a public agent working in the French Prime Minister’s services on digital issues. They desired to bring the dynamism seen in Civil Sector Organizations (CSOs) into government operations. During the course of COVID-19, CSOs had frequently proven themselves to be quicker and better able to meet the needs of people (e.g., showing nearby vaccination site availability) than the French administration.

Our first iteration of the problem – that the French administration was not able to meet the needs of the French people – reflected this understanding of the issue. However, when we tried to identify the ‘entry points’ where our authorizer could act, we quickly found that this was too broad. However, one of the branches, which focused on poor internal government coordination, seemed promising, with a lot of causes and sub-causes as well as the most likely place for our authorizer to act.

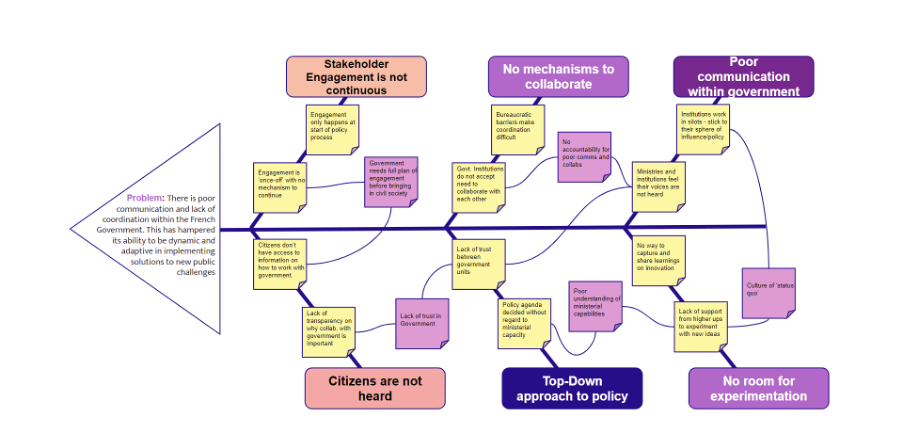

We brought these findings to our authorizer and together realized that coordination or working with CSOs was not the most important factor in the problem. Evidence suggested the French administration could identify the needs of the French people, but in the implementation of solutions to meet those needs poor government-to-government coordination was a barrier. By learning about the issue together, we along with our authorizer were able to find the right places for them to act and start an action learning agenda.

This process required several rounds of iteration on our problem statement. Though iterative learning pays dividends, as discussed before, we immediately learned that iterative work is hard. Team morale dipped as we felt that we were going backwards or had ‘failed’ in our previous problem definitions and had to ‘start again’. However, another learning was that iterative learning gets easier with time, as you are building on what you have already learned. Each iteration was not just an improvement on the problem, but an improvement on our teamwork as well as our psychological safety and coordination became stronger.

Some insights we learned about our particular problem through PDIA

The PDIA process allowed us to understand the high complexity of our problem, the numerous causes that affect it, and the interconnectedness of the sub-problems. While we do not claim to have become experts regarding the problem, we gained good insights during the PDIA process. We realised through iterations that the government’s focus on civil society to solve public problems is largely a symptom of its inability to solve problems internally. As we dug deeper into understanding coordination among government institutions, and the lack of thereof, we realised difficulties in solving these across the government made it feel easier to look outside at e.g. CSOs and private institutions to solve problems. The poor coordination and communication among government institutions has many causes, which vary from lack of know-how, to lack of capabilities/capacities, or even a reluctance to cooperate or share information, which in itself may be a symptom of some other causes, such as lack of trust between institutions.

While several of these things are not specific to France, we learned that it is important to remember that context matters. The bureaucratic and hierarchical nature of the French government and Executive has played a significant role in how the relationships between government units have taken shape. This in turn has affected the ability of government agents to be agile and flexible in solving problems. The attempts of the government to bring about digital transformation in France, while important, are often a proxy for other needs, such as better communication among government units/institutions or more efficient processes and coordination. Digital transformation and the involvement of CSOs will not automatically solve these ‘tricky’ issues.

For our authorizer, placed in an interministerial role, there is a real possibility to enact change, yet our iterations showed that this will be far from easy. For the authorizer, exploring the space for change will likely allow her to build authority outside her immediate mandate and role alongside other obstacles, such as lack of capacity or even resistance from others. The task the authorizer has taken is vast, but with the right support (and the right team), much can be achieved, even within a short period of time.

Words of wisdom to share

All of this gave us some key insights into working with PDIA. First, patience and perseverance are critical. As PDIA is a process that depends heavily on frequent iteration, it may take some time to identify the right problem or process for addressing the problem. In our case, we had many iterations of the problem statement before landing on one that was most relevant and accurate. This meant that in the six-week course, we spent nearly five weeks just identifying the problem! At times, this process was especially frustrating—especially when we had to draw and then re-draw the problem statement, fishbone diagram, and triple-A exercise. However, through this process we also learned how to exercise perseverance and patience. These two traits are particularly valuable when pursuing a career in public policy where problems and processes can very often be abstract and ill-defined.

Secondly, it is key to iterate early on and often. As noted in our last post, in order to move forward, it is crucial in PDIA to iterate over and over again. Though this was new and, at times, uncomfortable for us as a team, being able to iterate was particularly vital for problem identification. Rather than fixate on one problem statement, which would limit our ability to then design a relevant and targeted process, we kept generating new problem statements as we collected more data from our authorizer and other stakeholders. This process helped us critically examine our problem statement throughout the six-week period and iterate upon it so that it was more targeted, informed by data, relevant, and captured the heart of the issue at-hand.

Thirdly, PDIA is a process that can be uncomfortable and rife with uncertainty at times, so we strongly urge everyone who adopts this approach to exercise self-care and empathy—at an individual and group level. In our case, we made a concerted effort to get to know each other at a more personal level. We opened every team meeting by checking in on how everyone was doing—key areas of stress (beyond PDIA and even school), workload, etc. We also grabbed dinner outside of class to get to know each other outside of the PDIA context—this improved psychological safety and a feeling of community and belonging. The acts of kindness also enabled the team to appreciate each other and feel appreciated in return through small, yet extremely meaningful gestures of kindness. The bonds we grew as a team were themselves part of the process of learning- and we know we could not have made the progress we did without each other’s support and insight.

Photos:

Fishbone 1:

Fishbone 2:

Fishbone 3:

Fishbone 4:

Revised Fishbone:

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2022. These are their learning journey stories.