Guest blog by Razan Alayed, Aleena Ali, Ryan S. Herman, Cecilia Liang, Krizia Lopez

There were many lessons to be extracted from this course and through applying the Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) approach to our concurrently ordinary and extraordinary problem. The issue of teacher shortage has existed for many years and is persisting in the United States, with the pandemic exacerbating and laying bare the public education system. Through iterative thinking and discussions, we as a team were able to narrow and focus our problem to what was relevant to our authorizer and her context, as well as surface the causes that continue to influence the issue at hand. Specifically, the PDIA process has taught us to dig deeper into root causes and distill them into comprehensive understandings; in fact, we discovered along the way that some sub-causes are shared among larger entry points, which was pivotal to defining our ideas and action steps. This process taught us that starting with small ideas and growing them is key to the iterative approach, since we were able to take frequent pauses, reflect, modify and then go back into the solution space. This also allowed us to experiment with our ideas and to obtain timely feedback through stakeholder interviews prior to investing time and resources on ideas that may not work in our context. Suffice to say that this experience has been fruitful for our professional journeys, and we will be taking these learnings as we move forward in our careers.

Our Problem & Findings

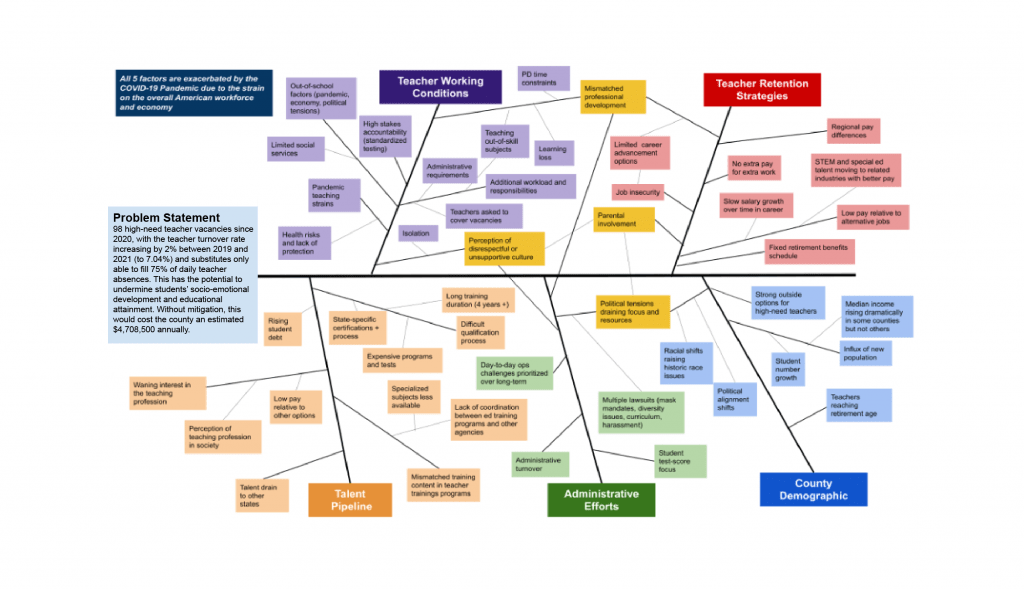

We began our PDIA journey with a school district in Virginia holding an overly strong commitment to a potential solution. Based on the US Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona’s Dear Colleague Letter, our initial problem statement on the rising teacher shortages across the United States led our group to simplify the problem to common rhetoric around the teaching profession. This centered around higher remuneration for teachers, which we felt would help alleviate the current undervaluation of teachers in US society, where lawyers, doctors, and engineers are lionized and the societal contribution of teachers is barely acknowledged. Although such assumptions do hold true to some extent, as the teaching profession is historically under-resourced from federal, state, and local governments, our initial fixation on perceiving our problem in the school district as a money matter was initially our greatest barrier to success.

By following the PDIA approach to problem definition, deconstruction, and ideation, our investigation into the school district context helped disprove our original assumptions. This was significantly aided by the generous support of teachers and administrators who gave up precious time in a period of staff shortages and packed schedules to speak with us. The district has historically offered competitive salaries for both full-time classroom teachers and substitute teachers, comparable to the US average. Throughout our conversations with different stakeholders, we repeatedly heard about teachers driving in from Maryland and West Virginia daily to benefit from the district’s compensation package. So if money wasn’t the problem, then what was driving teachers out of the profession?

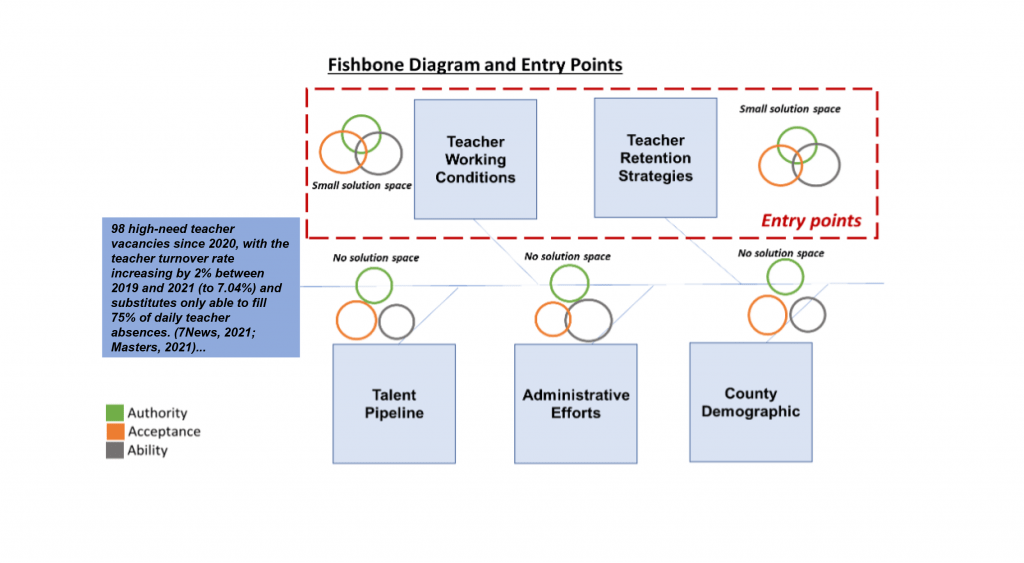

Speaking with a number of teachers and school leaders both internal and external to the school district context, we were able to deconstruct the problem of teacher shortages into a number of causes and sub-causes. Surprisingly, most of these were unrelated to teacher compensation. From one of our conversations with our authorizer, a Divisional Instructional Facilitator Rholyn Barnhart, we were given a helpful framework for considering these non-monetary sub-causes:

“There are very special components of being an educator that make teachers stay even when pay isn’t the best. However, what we see now, is that these components are no longer outweighing the costs of being underpaid. Your job is to investigate what these other components are and what has happened to them.”

In our work, we found and investigated a number of these components that have traditionally incentivized commitment to the teaching profession. However, one of the most prominent findings from our research was the uncovering of what we could call a culture of shared ownership and collaboration. Teachers are most supported when their school and district leadership fosters a healthy culture of collaboration across three subgroups: with school and district administration, with fellow teachers, and with parents and families. This collaborative culture has been under significant strain recently, with several political issues complicating effective collaboration between school administration, families, and classroom teachers, coupled with overall pandemic challenges. Therefore, we viewed this shared ownership and collaboration as a north star when we discussed the relative authority, acceptance, and ability we would have in using any entry points.

Upon conclusion of our six-week course, we shared with our authorizer the importance of leading the rejuvenation of the collaborative culture in the school district, starting with how her department can begin to prioritize collaboration with teachers. Our progress culminated in recommendations to examine current professional development practices as well as investigate positive deviants in teacher retention, by proactively speaking with teachers first. We decided to highlight the ultimate importance of teacher voices and lived experiences, since we will never get a true understanding of what is happening on the ground without teacher input, and because there is still so much we do not know.

Words of Advice about doing PDIA

- Trust the process and stay open-minded

Embrace the discomfort of not having any answers or solutions in the early stages. Initially, it felt daunting to have a very high-level problem statement and to try and turn that into concrete recommendations for intervention. Yet crucially, that vagueness is what enabled us to identify the underlying contributing factors behind that high-level problem. Ultimately, giving ourselves space to explore a problem fully openly without any preconceptions through each step of the PDIA process allowed us not to become overwhelmed by the vastness of the problem. Rather, we were able to focus on understanding how the smaller sub-factors fit together, and what changes can have the greatest impact on the problem. In other words, it is fine not to have clear answers initially, and it is important to let the PDIA process be as assumption-free as possible.

- Set communication and workstream norms

In order to maximize team effectiveness and culture it is important to have communication norms set out from the beginning, to establish trust and a good working culture. Writing out our processes and standards in the team constitution was a great way to ensure that our meetings always started and ended on time, that we set up ahead of each week who would oversee which tasks (which included leading the team meeting, preparing authorizer questions, editing the final assignment, etc.), and that we held each other accountable. Since we were working independently throughout the week, an in-person weekly meeting was an excellent way to keep each other updated on what we had learned separately and to embed those learnings into the group’s final output.

- Keep up the pace by creating weekly deadlines for the completion of various tasks

It is easy to feel lost or overwhelmed in the murkiest parts of synthesizing all the information you have gathered but being able to work towards a concrete product in each stage helped create momentum. In our case it was deadlines created through predetermined assignments, but in a real-life setting you could create that same momentum with a project plan or Gantt chart.

- Value debate, value the outliers, and value everyone’s perspectives

On some weeks, based on the independent components of research and interviews we had done, we did not easily agree on what were the most important aspects of the problem. However, these debates and dialogues proved to be a huge asset because it enabled us to filter out anything that was leaning too far in one direction. Holding different perspectives enabled our final products for each stage of the PDIA process to be well-balanced and high-level enough to address all the different aspects in a situated and objective way.

All in all – trust the process, embrace the discomfort of the unknown, and use structure and trust to build a thriving, productive team!

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2022. These are their learning journey stories.