Guest blog by Andrew McIntyre

Although a journey starts with a beginning and an end, it is the actual experiences that occur between those two points that are the most important. In this current period of COVID the experiences, while less hands-on, can be more intense and thought-provoking due to the time for reflection and the focus on alternate communication stimuli. Such was the case with the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education course that I recently undertook at Harvard Kennedy School. Beginning the course, I had the normal expectations of learning new skills, tools and interacting with people from all over the world to learn about how I could better implement my current projects. Little did I expect that the online learning, while delivering these expectations, also allowed me to be both the object and subject of active learning approach to exploring improved leadership and a participant observer of effective online interactions and perspectives. The progress of the course itself, mimicked the very tools that it shared, all of which seek to improve public policy in development situations.

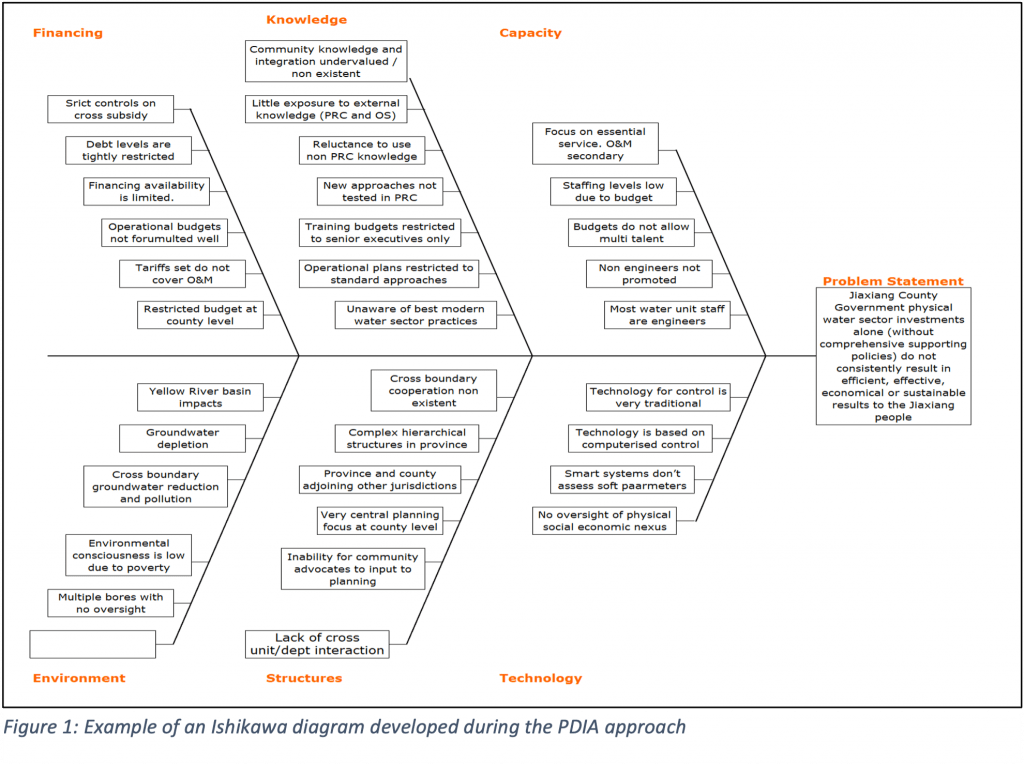

The key outcome for the course for me was the introduction of the Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) tool which uses an iterative, action-learning approach to identify, reduce, reflect, conceptualize and adapt solutions to the public policy problem situation. It is a dynamic process with tight feedback loops that are adaptable within local contexts and structures, focusing on functional change, problem solving and improved management of complex and changeable contexts. The beauty of the course was that while all participants actively adapted the PDIA tool to their own project focus, the course itself was an example of an active PDIA approach – adapting and reflecting on solutions, managing integration and achieving improved outcomes, despite the challenges.

The required assignment to adapt the PDIA approach and other learning to a personal project over a period of 6 months allowed participants to become the active participants in their own learning, ably guided by a strong faculty presence, but more importantly by a peer learning group tackling common problems. The peer learning group, a valuable facet of the PDIA approach itself, enabled project leaders to learn new ways to address what would seem to be common problems. Meeting more than fortnightly, the group provided situational feedback, discussion of multiple real world approaches, challenges and solutions, and active learning support. We each identified our problem situations, reflected on our learning, and explored new ways of utilizing authentic leadership tools to improve public policy outcomes.

Introduced during the active experimentation stages of our PDIA journey, were the four P’s approach to strategic leadership and how it can be used to build effective teams and actively harness key stakeholders to improve public policy outcomes. The 4 P’s are perception, process, people and projection. Perception ensures we examine our assumptions of others’ perspectives, given everyone can look at the same situation but in a completely different way. Process is well defined in most organisations’ manuals but understanding that there are multiple ways to reflecting on and managing normal routines and habits can be insightful. Emotional intelligence and understanding People’s motivation and emotions is essential for harnessing stakeholder involvement and ensuring movement towards improved outcomes. In order to align ones own goals with the myriad other storylines, Projection is required for consistent strategy and sustainable outcomes. The 4 P’s were an insightful approach to managing change and complexity within the public policy arena and were actively used by all members of the group.

My action learning application was a loan project currently under processing within the PRC. While comprising a normal infrastructure investment loan, it also includes a significant component for public policy reform. The PDIA approach entailed iteratively examining the root definitions of the problem situation, forensically enquiring, and grouping the causes and functional changes apparent within the project scope. These were documented using an Ishikawa (or fishbone) diagram, that was used to visually prompt internal reflection, external enquiry and understanding. An example developed during the approach is figure 1. Through the regular peer review meetings it became readily apparent that everyone was addressing similar problem situation and challenges within their own projects across 7 countries. The reflection, discussion and insight provided ample opportunity to experiment with new ideas, approaches and actions, in real time on a real project. It allowed us to reflect more broadly on how we could improve, specifically how I could improve, the approach to developing these and other projects; particularly those with a defined, or implied public policy component.

These group reflections also highlighted the challenges that we all face, not just under normal circumstances where sustaining real public policy change is already challenging, but also in this age of COVID where the absence of physical enquiry makes understanding and insight even more difficult. Actively participating in an extended online action learning course, demonstrated ways to motivate team members, and provided real world need to ensure stakeholders, gatekeepers and authenticators are fully involved in any project design. I was able to consider and reflect on my own project and how it could be implemented successfully, particularly now without the specific nuances and insights one would ordinarily gather.

While the course covers many areas that individually are common or similar within my organisation, the combined approach of an integrated toolkit, delivered itself within an active PDIA approach provided a compelling learning experience. The action learning constantly modified and expanded understanding of my project, and became a subconscious, active tool to continually assess and re-assess, question and explore options for change, for achievement, and manage my project’s inherent complexity. The communicative aspect through both formal written assignments and, more effectively, in remote peer group discussions, mimicked what in reality should be the status quo for any project division designing and managing a complex portfolio of projects.

While the course was a valuable insight into approaches for implementing public policy, there remains the need for adoptive team leaders and organisations to allocate time, resources and personnel to support such an approach – things that are often in short supply. Although organisations may be slower to adopt, I found that with a well-defined and organised team, frequent interaction (particularly if face-to-face), and mutual space for reflection, query and discussion, the PDIA tool combined with other systems based approaches would be an excellent way to take the design and implementation of development projects to a new level that is more sustainable and effective. Focussing on managing and querying that aspect of the overall project development situation, may prove to be the start of a more compelling outcome.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2020. These are their learning journey stories.