written by Matt Andrews

I was on a call two days ago with a former student who is now deeply involved in his country’s Covid-19 crisis response. He said something like the following: “Our government is not set up to respond to this; there are multiple challenges coming at us all at once, requiring multiple new ideas from multiple places, fast. We just can’t mobilize people properly.”

This is a comment I am sure many leaders would echo right now. You look at your bureaucracy and wonder if and how it will be able to handle this crisis. It’s a little like reflecting on whether a ship built for good weather can really manage a storm.

The truth is that it probably won’t.

Typical hierarchical control mechanisms seem like they give you the coordination you need in crisis (given that we often look to centralize control during such times) but we can’t control every part of the crisis through singular hierarchies, especially when crises require engagement beyond a single organization or geographic area. Also, no new crisis conforms to the pre-arranged organizational structures we have in our organizations. These structures are typically set up to deal with specific and discrete challenges—not compound problems like we face with threats like COVID-19 (where the initial threat of virus is extremely complex and has multiple knock-on effects).

This is precisely why those who have worked in crisis and disaster management suggest using new structural mechanisms to organize their response. Decentralized decision-making and coordination mechanisms are particularly advocated for use in this kind of situation (see Dutch Leonard’s video in blog post 8, the discussion of such structures in blog post 9, and the ‘part 4’ reference to such in the interview with Shruti Mehrotra in blog post 10).

What matters is that these mechanisms allow you as the leader to identify where decisions need to be made, access information (as best as possible) and ideas to make those decisions, mobilize agents to act on and implement those decisions, and constantly monitor those actions to adapt the decisions as necessary.

In blog post 9 I emphasized that there are different kinds of such mechanisms. My work on problem driven iterative adaptation (PDIA) has found Marshall Ganz’s snowflake structure as an accessible, organic mechanism to help countries think about organizing themselves to address major problems (often related to crises).

In this blog I want to reflect—very briefly, but with references for your additional reflection—on how Liberia adopted a new organizational mechanism that has elements of the snowflake (being relatively flat, fast, and flexible) to coordinate and empower decisions in response to the 2014 Ebola epidemic. I summarize the story from Liberia as well as I can in this short blog, drawing particularly on two key articles, from Princeton University’s amazing Innovations for Successful Societies case series by Leon Schreiber and Jennifer Widner (or SW), and the Journal Health Systems Reform by Tolbert Nyenswah, Cyrus Engineer and David Peters (or NEP). I am not sharing this to suggest that the Liberian Incident Management System (IMS) is the best practice for you to copy or mimic. Rather, the story shows that,

- Governments need to create new structures in the face of crisis,

- You can do this mid-stream—pivoting when you learn you need to,

- Even countries with limited resources—like Liberia, and perhaps like some of your own countries—can do it,

The blog is quite long (I apologize) but you will see questions interspersed for your reflection.

Relating the case to you, the reader

Remember the question I started this blog with, from a former student now playing a key role in his country’s COVID-19 response: “Our government is not set up to respond to this; there are multiple challenges coming at us all at once, requiring multiple new ideas from multiple places, fast. We just can’t mobilize people properly.”

Liberia was no different and its initial organizational response proved limited as a result. But it pivoted organizationally, changing HOW they did things, not just WHAT they did.

Where Liberia started

Liberia’s government was a hierarchical bureaucracy—as I suspect is the norm for the organizations most public leaders oversee. Many ministries existed, all operating quite separately from each other and each broken down further into sections, departments, agencies, etc. It did not work well: “This system was bogged down with bureaucratic bottlenecks and therefore was not very efficient in its operations” (NEP, 199).

Beyond limited operationality, the system also lacked openness, with the “hierarchical relationships and communications … limit[ing] engagement of stakeholders.” This led to “an uncertain ability [within the system] to take on crisis leadership tasks” (NEP, 199).

Government initially responded to the crisis within this system, as most governments do.

The President created an Ebola National Task Force in July 2014, “consist[ing] of high-level representatives of Liberian government ministries, foreign governments, and international organizations” (SW, 2). Decisions emanating from this Task Force were channeled to the structures created around a National Public Emergency Task Force, which had been created in March by the country’s Chief Medical Officer (Bernice Dahn) under the authority of the Minister of Health (Dr. Walter Gwenigale). Dahn created “technical committees within the health ministry to facilitate the main functions the task force aimed to carry out…” (SW, 3).

As NEP (199) describe, leadership in this structure “remained centralized and hierarchical, with many actors involved, though not organized to make effective decisions or communicate effectively … and not well adapted to the urgency and magnitude of the situation.”

This response failed “[as] the procedures put in place … quickly proved inadequate” (SW, 3). Reasons for this were numerous, and you may be experiencing them in your context already, if you are trying to respond using preexisting structure that were not designed for crisis response:

- The structure did not foster coordinated decision-making and action across ministries: “[The] response required the cooperation of other ministries that controlled port, airport, finance, and other critical functions, but decision making did not adequately involve those other government departments” (SW, 3).

- The structure had built in bottlenecks. “[The structure put too much emphasis on Dahn’s role], which meant that “[she] herself was thoroughly overburdened. By channeling all decisions and actions through her and through the health ministry, the task force design caused bottlenecks and also led to the neglect of other health-care issues. Dahn had no deputies who could assume some of her duties when, for instance, she had to attend to non-Ebola-related matters or several problems arose at once” (SW, 3).

- The structure had information sharing and monitoring limits. “Amos Gborie, Liberian deputy director of environmental and occupational health services … said there also was no system to monitor progress and “no information sharing. . . . No one knew what was happening.”” Furthermore, “Ministries, local governments, clinicians, nongovernmental organizations, suppliers, and donors lacked a way to track actions taken—a vital capability when different organizations divided labor” (SW, 3).

- The structure suffered from logistical constraints, which fragmented action. “Limited infrastructure also impeded effective action. Those responsible for directing key functions worked in different parts of the capital. The group that dealt with medical aspects of the response operated from the health ministry’s building on the outskirts of Monrovia. But the logistics people were based across town in the offices of the General Services Agency, which managed government property. The result of such fragmentation was that “people were meeting all around the place,” said Tolbert Nyenswah” (SW, 4).

- The structure actually fostered ‘scattering’. This was especially apparent in communications, where “Every government agency, NGO, and religious group projected its own message, or so it seemed. According to Robert Kpadeh, deputy information minister at the time, “the way you fight Ebola basically [depends] on the dissemination of information . . . [but in] the beginning, we had a serious challenge with a scattered approach” (SW, 4).

- The structure fostered “suspicion leadership”, which Leonard Marcus describes as a situation “characterized by selfish ambitions; narcissistic actions; grabs for authority and resources; credit taking for the good and accusations for the bad; and an environment of mistrust and back stabbing.” The many different actors did not work together or take common responsibility for action, leading some to suggest that responses were “politically driven and politically focused” and subject to “the spread of rhetoric over action” (NEP, 199). NEP (199) note that, “Everyone wanted to be in control or thought they knew the best approach in responding to the crisis. This bickering was so pronounced that discussions, which should have been monitored and confidential, were circulated in minutes to a wide email chain and media outlets. With this kind of unsolicited access to response discussions, the New York Times published an article detailing key elements of these discussions and bickering, much to the chagrin of the government.”

I wonder if we can pause here and have you reflect on how your country is doing in its organizational response?

- Are you finding that your structures are buckling, failing to foster a common response, or even allowing some kind of ‘suspicion leadership’ to take over?

- Can you make a list of the organizational efficiencies you see occurring now?

How Liberia pivoted

A pivot occurred in July 2014 because Liberian officials—and development partners—recognized that these organizational structures were not working—there were too many decision and operations gaps.

The officials did not jump to any one best practice new model of organization, however. At a meeting with members of the USA Center for Disease Control (CDC) World Health Organization (WHO), and government officials weighed the pros and cons of two operational structures—a United Nations Cluster System approach and a dedicated Incident Management System (IMS) proposed by the CDC. The Liberians decided on the latter, the IMS, which had been used to address health emergencies in other contexts in the past, could be quite easily adapted to contextual conditions, and placed Liberians in the leadership roles (SW, 6).

The IMS was a completely new organization that “would separate Liberia’s Ebola response from the rest of the overburdened health service, designate a single contact point for each main function, and coordinate all organizations around task teams under its umbrella” (SW, 6).

Tolbert Nyenswah, assistant minister of health for preventive services and deputy chief medical officer, was appointed to head the IMS by the minister of health, at the behest of the president, and charged with the sole responsibility of leading Liberia’s national Ebola response (NEP 200).

Notice that the President herself gives the day-to-day work away in this action, but with clarity and trust. The clarity of this delegation was vital: firstly in authorizing Nyenswah to direct the work of even more-senior officials; secondly in ensuring he “had direct access to the presidency” and the “authority to make decisions on moving the response forward” (SW, 7); and thirdly in separating the leadership of day-to-day work from higher-level political decisions (and taking the President ‘out of the weeds’ to focus more on those higher-level issues).

The President’s high-level decision making role was also reframed, as the head of a renamed and refocused President’s Advisory Council on Ebola (PACE). While the IMS would do the day-to-day crisis response coordination, PACE focused on ensuring “rapid action on high-level policy decisions regarding such issues as school closures, cremation policies, safe burial practices, and border closures” (SW, 8). The need for many of these decisions was raised through the IMS; but higher-level authority was required because “no matter how much political authority was vested in the leadership of the IMS, there [were] certain decisions that needed to be taken elsewhere” (SW, 8).

The following quotes from the Princeton study help to differentiate the roles of IMS and PACE:

“The IMS operated under a planning horizon of 24 hours in managing the day-to-day response, but PACE provided a mechanism to “escalate things that weren’t day-to-day issues.” … PACE’s longer planning horizon additionally provided an opportunity “to simultaneously consider wider issues in the health-care system” such as the restoration of normal health-care services” (SW,8).

“In addition, by providing a platform whereby the president and senior ministers could stay abreast of the latest developments in the response, PACE provided “a kind of check and balance that ensures that what needs to happen is in fact happening”. That oversight role also served to “keep all of the political [actors] involved” … “We wanted to keep the country and all of its leaders still engaged, because you didn’t want people breaking away and feeling irrelevant in the process.” [So], PACE could be regarded as “a high-level strategic decision-making and monitoring system within the [overall coordination] structure” (SW,8).

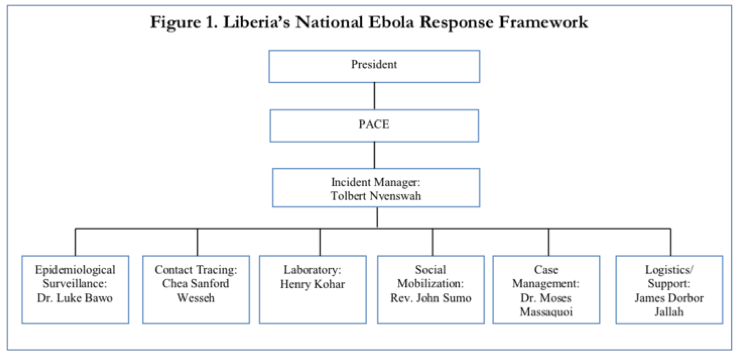

The IMS itself focused on day-to-day operations, emerging as a flat structure (under Nyenswah’s leadership) with different ‘teams’ working in various thematic areas. The thematic areas included surveillance and epidemiology, laboratory diagnosis, case management, contact tracing, case investigation and active case finding, dead body management and safe burials, logistics, county coordination, and social mobilization/psychosocial support) (NEP, 200).

Thematic teams were headed by Liberians with adaptive leadership qualities (and with international partners as co-leads to ensure consistency with international responders). “Theme leads [were] selected from within the core [Ministry of Health] professional staff based on ability to think analytically and respond rapidly. Selection was not based on seniority. It was critical that Liberians themselves took the leadership role in curbing the epidemic.”

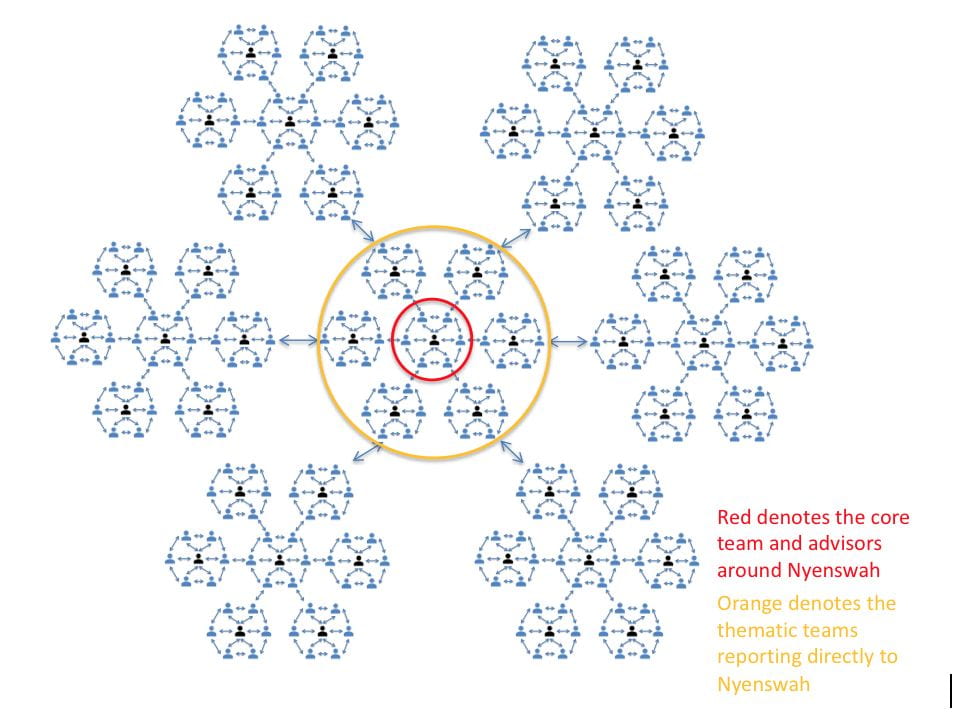

Team leaders managed small groups, with the working principle that the span of control—the number of people reporting to a senior manager—not exceed 5 to 1. Team leaders would interact with sub-teams to allow greater reach and engagement, and a number of the thematic teams ultimately managed many teams of volunteers and county level officials across the country—all organized into small teams themselves.

The core set of thematic teams met every day at 10 am (after Nyenswah had met, at 8 am, with his own ‘inner core of advisors’) (NEP, 200). The various gatherings were carefully structured to allow team leads to report back on activities, engage in debate about issues arising, and receive new task orders from Nyenswah (who allowed and encouraged debate but always provided the final authoritative word, being the authorizer and convener of the entire initiative).

A version of the PACE/IMS organizational chart is provided in SW (page 7). (See another version in Pillai, Nyenswah, et al. 2014). It shows that the structure had some hierarchy, but was actually very flat, fast and flexible.

I think that one could also use a snowflake structure to show the organization, at least for the IMS, as follows (with Nyenswah’s core team at the center of the snowflake and an immediate set of thematic teams in the second ‘ring’ of the nucleus, and many other teams distributed but connected through the second ring thematic teams).

The visual representation shows how much reach and engagement this kind of structure allows. Both papers I have cited provide useful details of the procedural and organizational structures used in the PACE/IMS organization, and I advise anyone interested to read these. The following descriptions by NEP (200-205) are, however, instructive in demonstrating the structure’s key characteristics:

- It was a flat structure that encouraged distributed leadership: “This was a “new organizational structure with fewer layers—a distributed leadership approach [characterized by] …Flat hierarchies and targeted teams with specific tasks…” [all having] “clear authority and accountability” [that] “opened the way for active decision making through empowered teams and crisis coordination … through continuous communications …”“This approach acknowledged leadership at different levels in the government and communities, not just formal leadership. The unit shifted from few designated officials to a broader group of task forces that had clarity of roles and authority to be successful.”

- It was a fast structure built around daily, evidence based decisions and action: “Decisions were taken and reviewed daily on the basis of available data and communicated intensively within the health system, with the population, and with international stakeholders.” “The thematic groups had clear mandates, design features, and, more important, common guiding principles to ensure success. The operational principles for the daily meeting of all of the thematic groups and limiting the numbers of people at the meetings ensured timely, accurate, and reliable communication and effective decision making.”

- It was a flexible structure, allowing different views and fostering debate and learning: “It also allowed for cross-thematic brainstorming and impact and consequence analysis for all decisions. Though thematic groups may argue over best strategies and approaches together, at the end there was consensus and buy-in due to involvement.”

Probably the most important thing to say about the structure is that it is generally agreed to have had a meaningful impact on both the efficiency and effectiveness of the government’s response to the Ebola epidemic (see NEP, 204): “Although the epidemic started later and resulted in more cases in Liberia than in Sierra Leone and Guinea, the effectiveness of the distributed approach taken by the IMS helped Liberia get through the emergency phase more rapidly than the other countries.”

Now, it is your turn to reflect on your own organization:

- Do you think that it is necessary to separate the high-level political decision-making and day-to-day operational work in your government’s crisis response?

- Who would you see being in the high-level task force structure (like PACE)?

- What kind of person would you see leading the operational structure (the IMS)? What characteristics would that person have?

- What thematic teams would you create through the IMS?

- What kind of people would you see leading the thematic teams? What characteristics would those people have?

To conclude, you may want to watch the following brief interview with Peter Harrington (conducted via Zoom) on his views about the IMS and the roles of people in the IMS, the roles of Tolbert Nyenswah and President Sirleaf, and more.

The Public Leadership Through Crisis blog series offers ideas for leaders questioning how they can help and what kind of leadership is required in the face of a crisis (like the COVID-19 pandemic).