Guest blog written by Rina Arlianti, Stephanie Carter, Murni Hoeng, Siti Ubaidah Idrus, Susanti Sufyadi, Aaron W Watson.

This is a team of six development practitioners working for Indonesia’s Ministry of Education and Culture, the Tanoto Foundation, the Australian supported INOVASI program, and Australian Embassy, Jakarta. They successfully completed the 15-week Practice of PDIA online course that ended in May 2019. This is their story.

The Harvard BSC’s PDIA course has been an exciting journey for all of us. We began the course full of excitement and hope – with most of group members having not met before. We were one of four groups participating from Indonesia, all focused on the issue of education quality. Over the course of 15 weeks, we navigated the twists and turns of the PDIA process, putting key concepts to the test in the field of basic education in Indonesia.

Early on, once we had settled into our group dynamic, we settled on our problem statement:

Learning outcome quality in Indonesian primary schools is still low (low scores in international standardised student tests)

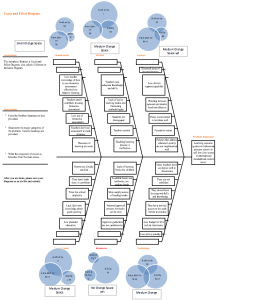

As we progressed, we gained several key insights and takeaways about our problem and the course. Through group discussion and debate, drawing on perspectives from working both within and outside the government system, we settled on the following six key sub-causes for low learning outcome quality in Indonesian primary schools:

- Measures of learning are weak (including the use of formative assessment, due to low teacher knowledge)

- Teaching/learning process is ineffective (with teachers lacking inadequate skills and knowledge of how to use learning media, to increase student engagement)

- Parents are already satisfied with the status quo (there is often low demand for changes to the system, as parents do not know what good teaching looks like)

- Lack of learning books for children (due to cumbersome book supply processes at the national level)

- Many teachers don’t use digital technology in classrooms (creating missed opportunity for enhanced learning)

- Policies that address education quality are not implemented well (and instead focus on physical infrastructure, or if they do exist, are not socialised well in a decentralised system)

It was important to examine the authority, acceptance, and ability of these sub-causes, so that we could prioritise what issues to work on first. In thinking about whether there was more or less space than we had previously assumed, this was dependent on the particular cause or sub-cause. Where our strategy needed to focus more so on strengthening ability, there seemed to be more space to change. When it came to acceptance and authority, there was generally less space to move. In the Indonesian education sector context, many socio-cultural and political factors influence acceptance and authority over education quality and improving student learning outcomes, while ability is a bit easier to address as it is more technically focused. For some causes that we know are ‘hot topics’ within the Ministry of Education and Culture, or for topics that are highly politicised or have very little political support, the space for change is dramatically less than previously assumed. However, the process showed that we can take initial steps and identify entry points for early action, to start expanding this space for change – even on the difficult issues.

As we moved into the iteration phases, our mind sets were tested and we were forced to think more practically about our sub-causes and solutions. This was challenging at times. These later modules showed that there can be some structure around the PDIA approach, which is useful for practitioners at the field level, when addressing an intractable problem. For example, moving from having multiple ideas, acting on them, then revising and reflecting, then taking more action – and all within a certain time period in order to gain and maintain momentum. The course also reinforced the idea that reflection and experiential learning is vital for PDIA, so that adjustments can be made along the way, and new ideas can be acted upon. Without this, ideas would remain stagnant and we would not be able to gain quick wins and enhance the chance of success in solving the problem.

While we were able to act out several of our planned iterations and actions, some were more challenging. For some tasks, we weren’t able to fully test our assumptions as due to timing and a range of factors (including impending holidays, Ramadan, and school exams), we weren’t able to carry the task out fully. We were pleased we could re-group and re-focus as part of the PDIA process, and we learned that our small successes build greater momentum long term.

Moving forward, we felt that our team members would most certainly look to use the PDIA approach at work and in our own programs. For programs like INOVASI, the PDIA approach is already in use as part of pilot design, implementation, and advocacy strategies. When working within the government system, the approach may be useful in connecting further with districts and provincial governments, to unpack and address key issues hindering education quality and learning improvement. This may be done through future workshops and discussions. We plan to meet up as a team to celebrate our achievements and will look for ways for bring together our team members with others who have done the PDIA course in recent times – we think there is certainly interest from several organisations and programs about how we can learn from and support each other in these endeavours.

To learn more, visit our website or download the PDIAtoolkit (available in English and Spanish) or listen to our podcast.