written by Matt Andrews

Last week I blogged about the ‘public policy futility trap’ in which countries get stuck when a negative feedback loop institutionalizes itself in the public policy domain. Experiences of past policy failure erodes the confidence (of citizens and public officials) to deliver in future, which undermines the potential for positive future policy results, which in turn reinforces the view that government cannot ‘get things done’, and on and on and on.

I think many countries are stuck in this trap, where negative feedback loops frustrate effort after effort to improve government capabilities. Initiatives designed to help governments get things done tend to fail when no one (in the citizenry or government) actually believes government can get things done.

So, how do governments get unstuck?

This is the question we plan to address—in practice —through the forthcoming Implementing Public Policy executive education course (starting in May 2019). The answer we suggest is simple: challenge the existing negative feedback loop by promoting cases of implementation success that can become the basis of new positive feedback loops—that help citizens and officials believe that more is possible tomorrow than it was yesterday.

We suggest a basic starting point for this strategy: public policy officials need to develop a clear view on what ‘policy success and failure’ looks like and measure and communicate how often policies succeed or fail.

In essence, governments must be able to demonstrate how often public policies really fail.

This is a fundamental starting point in the strategy to escape futility traps because perceptions of success or failure influence the feedback loop that shapes how people think about government capabilities.

Unfortunately, however, most governments (and other public policy organizations) do a really bad job of defining success or failure or of measuring and communicating the rate at which they succeed or fail. They either can’t do it (because they have not thought hard enough about what success and failure looks like) of they don’t do it (because they don’t evaluate or communicate the evaluation results).

In the absence of such proactive definition, measurement, and communication of actual policy results, sentiment about government performance is often shaped by negative headlines based on specific stories of failure or on citizen surveys of ‘satisfaction’ or ‘trust’ that studies suggest commonly reflect media-influenced frustration with economic and political conditions rather than experience or evidence-informed views on government policy success or failure. I believe that these stories and survey stats tend to be biased towards negativity and fuel the futility trap’s negative feedback loop.

This paper examines the way in which a public policy organization—the World Bank—does define, measure, and communicate its success.

I think it helps to inform the discussion. Some highlights include:

- The World Bank’s dominant approach to evaluating success focuses on the extent to which projects satisfactorily delivered on promised outputs (and, in some cases, outcomes closely associated with delivering those outcomes) in time and within budget. Given this approach, the Bank claims a success rate exceeding 75%.

- A second approach the World Bank uses to assess success involves reflecting on the ‘risk to development outcomes’—capturing how confident project leaders are that project outputs will sustainably solve the development problems that warranted a policy response in the first place. The Bank does not refer to this measure often, partly (I think) because it suggests a success rate of about 50%.

I think it is amazing that the World Bank evaluates all of its projects and that all of its evaluations are available for the world to see, and I hope my reflection on the evaluation approach the organization employs is not seen as too tough a critique. I actually think that the Bank’s approach and findings—about ‘how often policies succeed or fail’—offer many important lessons for public policy officials in general.

- First, I think that the organization’s standard ‘project satisfaction’ assessment is a good reflection of how its own staff sees their results. They focus on what they can be held responsible and accountable for—given the plan and control mechanisms they use in policy implementation. And the 75% success rate in delivering what they can plan for and control shows that they are doing a pretty good job of this.

- Second, I think the organization’s ‘risk to development objectives’ assessment is a good reflection (or at least an effort at capturing such reflection) of what policy recipients might think of success: what is the chance that this project actually address real problems? And the 50% success rate signals that the Bank has more work to do here.

What I propose in the paper is a combined success indicator, for the Bank and for policy organizations, that reflects on two sets of ‘beholders eyes’ to consider in developing this view: (i) officials who develop and implement policy and (ii) citizens and other policy recipients.

These two groups’ perceptions of success or failure are central to the futility trap; they are the ones who perceive whether policies succeed or fail, and this perception is key in influencing which feedback loop is influencing how people think about government capabilities.

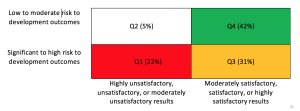

Acknowledging that they have different vantage points in looking at success is, I think, useful. But the vantage points can be combined to allow both groups a view on each other’s reality, as in the figure. It combines considerations of ‘satisfaction’ in delivering on a time-and-budget-bound project (the concerns of policy officials) on the horizontal axis and the concern for longer-term development impact (citizen and policy recipient concerns about whether the problem been solved or not) on the vertical axis.

As is evident, the result of merging these two viewpoints allows one to get a nuanced view of success and failure. One can see the percentage of policy interventions (taken from a sample of 385 World Bank projects completed in recent years, as decribed in the paper) that are considered both moderately satisfactory or better and low to moderate risk to development outcomes. This is a 42% sample of interventions that were done satisfactorily in the short run and are expected to deliver what is needed in the longer run: making everyone happy.

One can also see the portion of interventions that failed in both respects (the 22% in Q1) and the set of interventions that were satisfactory in the short-run (where officials have done their duty) but where concerns exist about longer-term impact (the interest of recipients).

A two-view approach to evaluating and communicating policy success and failure

Imagine if all governments could communicate their policy results in this way? In my opinion, it would go a long way to help governments escape the ‘public policy futility trap’:

- Governments could show that—actually—they succeed quite a lot…in an outright sense 42% of the time, and in the short-run things that can be controlled a further 31% of the time. Having data like this helps to counter the negative story and survey based perceptions on success that tend to promote negativity.

- Governments could also use this to develop implementation strategies to improve performance—a key part of the positive feedback loop necessary to escape the futility trap. For instance, World Bank officials can see here that the internal view on policy success is quite a lot higher (with 73% of projects more than moderately satisfactory) than what I have suggested is the external view (with only 47% considered low to moderate risk of development outcomes). This view suggests that the Bank should be trying to push more projects from Q1 and Q3 to Q4, which means managing risks to development outcomes better. The capabilities needed to manage these risks—especially when such are poorly defined—are often quite different to the capabilities needed to deliver on plan and control projects—where one can define and plan for and control most things that matter. Building a strategy to shore up these new capabilities and perform better in the areas of weakness will help policy organizations like the Bank reinforce the positive feedback loop necessary to escape a public policy futility trap.

I am excited to work on this kind of issue with practitioners involved in policy design and implementation in the upcoming Implementing Public Policy executive education program. I expect we will all learn a great deal about how regularly policies really fail and about changing perceptions that failure happens ‘so often’. In the meantime, this paper is a genuine working paper and I’d welcome any thoughts on it you might have.