written by Matt Andrews

Polls suggest that governments across the world face high levels of citizen dissatisfaction, and low levels of citizen trust. The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer found, for instance, that only 43% of those surveyed trust Canada’s government. Only 15% of those surveyed trust government in South Africa, and levels are low in other countries too—including Brazil (at 24%), South Korea (28%), the United Kingdom (36%), Australia, Japan, and Malaysia (37%), Germany (38%), Russia (45%), and the United States (47%). Similar surveys find trust in government averaging only 40-45% across member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and suggest that as few as 31% and 32% of Nigerians and Liberians trust government.

There are many reasons why trust in government is deficient in so many countries, and these reasons differ from place to place. One common factor across many contexts, however, is a lack of confidence that governments can or will address key policy challenges faced by citizens.

Studies show that this confidence deficiency stems from citizen observations or experiences with past public policy failures, which promote jaundiced views of their public officials’ capabilities to deliver. Put simply, citizens lose faith in government when they observe government failing to deliver on policy promises, or to ‘get things done’. Incidentally, studies show that public officials also often lose faith in their own capabilities (and those of their organizations) when they observe, experience or participate in repeated policy implementation failures. Put simply, again, these public officials lose confidence in themselves when they repeatedly fail to ‘get things done’.

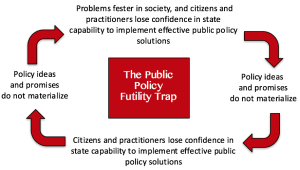

I call the ‘public policy futility’ trap—where past public policy failure leads to a lack of confidence in the potential of future policy success, which feeds actual public policy failure, which generates more questions of confidence, in a vicious self fulfilling prophecy. I believe that many governments—and public policy practitioners working within governments—are caught in this trap, and just don’t believe that they can muster the kind of public policy responses needed by their citizens.

Along with my colleagues at the Building State Capability (BSC) program, I believe that many policy communities are caught in this trap, to some degree or another. Policymakers in these communities keep coming up with ideas, and political leaders keep making policy promises, but no one really believes the ideas will solve the problems that need solving or produce the outcomes and impacts that citizens need. Policy promises under such circumstances center on doing what policymakers are confident they can actually implement: like producing research and position papers and plans, or allocating inputs toward the problem (in a budget, for instance), or sponsoring visible activities (holding meetings or engaging high profile ‘experts’ for advice), or producing technical outputs (like new organizations, or laws). But they hold back from promising real solutions to real problems, as they know they cannot really implement them (given past political opposition, perhaps, or the experience of seemingly interactable coordination challenges, or cultural pushback, and more).

This results in policy communities that generate ideas and even spend money in service of these ideas, and produce outputs they think might be useful in addressing the problem. But that never really solve the problems, which continue to fester, causing citizens and practitioners to increasingly see public policy interventions as futile.

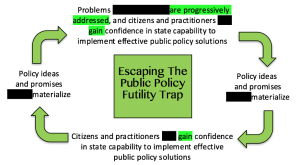

For a number of years, I—along with my BSC colleagues—have been asking if it is possible to escape this ‘public policy futility’ trap, and what an ‘escape strategy’ might look like. Our applied work and research has generated a number of ideas and actionable strategies in response, and we are excited at the results we see. The gist of our work is simple: The futility trap gets interrupted when policy communities develop their own capabilities to actually implement their own ideas more effectively than they have done in the past.

Whereas the gist of our work is simple, the work itself is not. It takes a lot to improve implementation capabilities in policy communities that have lost confidence in their capability to implement. These communities often even outsource their implementation responsibilities, or use other methods to separate their policy-making and implementation activities. However, we have found— through over a decade of real-world engagement—that much progress is possible (and quickly) where policymakers tackle their implementation responsibilities in new ways, and open themselves to learn actively about the many management methods available to implement policies, no matter how complex or scary.

We at BSC are very excited to be at a point in our own learning journey—of how to escape the public policy futility trap—to offer a new opportunity for policy executives interested in ‘learning to escape’. This opportunity comes in the form of a new executive education program at the Harvard Kennedy School, the Implementing Public Policy (IPP) program.

This program launches in May 2019 and breaks new ground for executive training programs. Participants will be involved in a seven month journey of learning rather than a typical one or two week period. Participants will work on their own real policy problem, with their own policy implementation teams. And the work will blend online, in-person and applied action learning (where participants learn-by-doing) to ensure that new ideas are shared, tried, adapted, and made useful for everyone who attends. Finally, every participant will become part of Harvard Kennedy School’s Implementing Public Policy Community of Practice, a productive network of professionals committed to improving public policy implementation around the world.

This program’s goal is to help policy practitioners—and communities —escape their ‘public policy futility’ traps by equipping them with both the skills to analyze policies, as well as the field-tested tools and tactics to successfully implement them. For more information, visit the course website.

Stay tuned for more videos and papers on this topic over the next few weeks!