written by Matt Andrews

We at the Building State Capability (BSC) program have been working on PDIA experiments for five years now. These experiments have been designed to help us learn how to facilitate problem driven, iterative and adaptive work. We have learned a lot from them, and will be sharing our lessons—some happy, some frustrating, some still so nuanced and ambiguous that we need more learning, and some clear— through a series of blog posts.

Before we share, however, I wanted to clarify some basic information about who we are and what we do, and especially what our work involves. Let me do this by describing what our experiments look like, starting with listing the characteristics that each experiment shares:

- We have used the PDIA principles in all cases (engaging local authorizers to nominate their own problems for attention, and their own teams, and then working on solving the problems through tight iterations and with lots of feedback).

- We work with and through teams of individuals who reside in the context and who are responsible for addressing the problems being targeted. These people are the ones who do the hard work, and who do the learning, and who get the credit for whatever comes out of the process.

- We work with government teams only, given our focus on building capable states. (We do not believe that one can always replace failed or failing administrative and political bodies with private or non profit contractors or operators. Rather, one should address the cause of failure and build capability where it does not exist).

- We believe in building capability through experiential learning and the failure and success such brings (choosing to institutionalize solutions only after lessons have been learned about what works and why, instead of institutionalizing solutions that imply ex ante knowledge of what works in places where such knowledge does not exist).

- We work with real problems and focus on real results (defined as ‘problem solved’, not ‘solution introduced’) in order focus the work and motivate the process (to authorizers and to teams involved in doing the work).

- We—the BSC team affiliated with Harvard—see ourselves as external facilitators of a process, and do not do the substantive work of delivery—even if the results look like they won’t come. Our primary focus is on fostering learning and coaching teams to do things differently and more effectively; we have seen too many external consultants rescuing a delivery failure once and undermining local ownership of the process and the emphasis on building local capability to succeed.

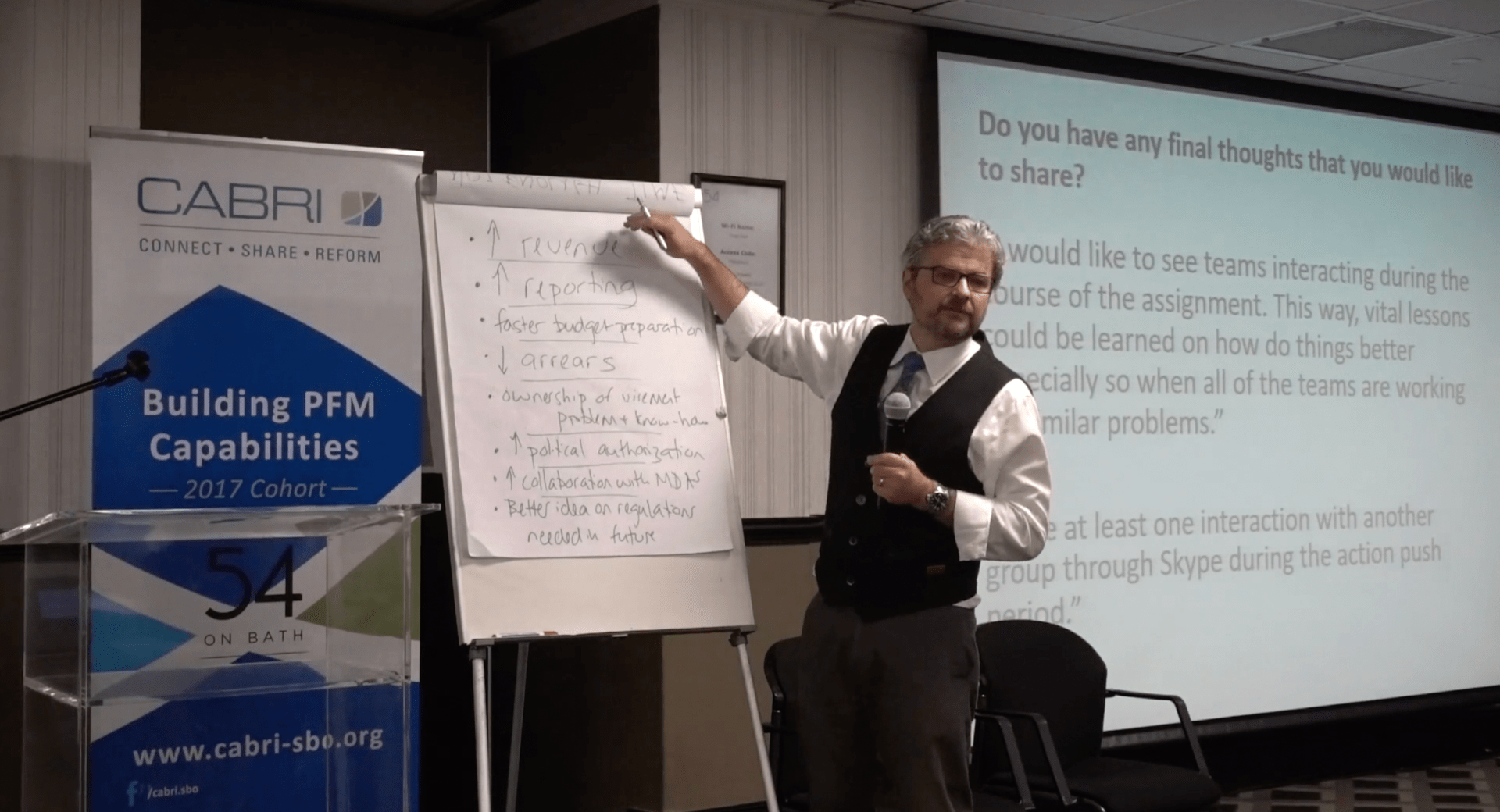

This set of principles has underpinned our experimental work in a variety of countries and sectors, where governments have been struggling to get things done. We have worked in places like Mozambique, South Africa, Liberia, Albania, Jamaica, Oman, and now Sri Lanka. We have worked with teams focused on justice reform, health reform, agriculture policy, industrial policy, export promotion, investor engagement, low-income housing, tourism promotion, municipal management, oil and electricity sector issues, and much more.

These engagements have taken different shapes—as we vary approaches to learn internally about how to do this kind of work most effectively, and how to adapt mechanisms to different contexts and opportunities:

- In some instances, we have been the direct conveners of teams of individuals, whereas we have relied on authorizers in countries to act as conveners in other contexts, and in some interactions we have worked with individuals only—and relied on these individuals to act as conveners in their own contexts.

- Some of our work has involved extremely regular and tangible interaction from our side—with our facilitators engaging at least every two or three weeks with teams—and other work has seen a much less regular, or a more light touch interaction (not meeting every two weeks, or engaging only be phone every two weeks, or structuring interactions between peers involved in the work rather than having ourselves as the touch point).

- We have used classroom structures in some engagements, where teams are convened in a neutral space and work as if in a classroom setting for key points of the process (the initial framing of the work and meetings at major milestones every six weeks or so), but in other contexts we work strictly in the environments of the teams, and in a more ‘workplace-driven’ structure. In other instances, we have relied almost completely on remote correspondence (through online course engagements, for instance).

There are other variations in the experiments, all intended to help us learn from experience about what works and why. The experiments have yielded many lessons, and humbled us as well: Some of these experiments have become multi-year interactions where we see people being empowered to do things differently, but others have not even gotten out of the starting blocks, for instance. Both experiences humble us for different reasons.

This work is truly the most exciting and time consuming thing I have ever done, but is also—I feel deeply—the most important work I could be doing in development. It has made my sense of what we need in development clearer and clearer. I hope you also benefit in this was as we share our experiences in coming blog posts.