Guest blog by Maria Viggiano

As America faces a national reckoning over racial injustice and the over-policing of communities of color, the concept of “defunding the police” has become a hot topic in various cities including my hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut. As Connecticut’s largest city, Bridgeport is home to over 145,000 people, the majority of whom identify as Black, Latino, or Asian Americans. The Bridgeport Police Department has suffered from a series of scandals over the last several years.

In 2017, a Bridgeport police officer shot and killed an unarmed Latinx youth, 15-year-old Jayson Negron. In 2018, the top aide to the Bridgeport Police Chief was fired after the discovery of numerous racists texts directed at African-American police officers in the department. Earlier this fall, the police chief himself was arrested by the FBI and later indicted on federal corruption charges. The demands for reform reached fever pitch this summer with local activists calling for a defunding and dismantlement of the Bridgeport Police Department.

The concept of “defund the police” is a relatively new one within the realm of public policy. The movement in favor of this approach emerged almost entirely from the activist community in the wake of recent nationwide protests against police brutality, especially in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. There are few academic papers or studies available that evaluate the effectiveness of specific policies aimed at reallocating public funds away from law enforcement departments and toward social service departments like housing, health, and education. However, ample academic research does definitively point to the short- and long-term payoff of investing in these areas as a preventative strategy for minimizing societal ills such as poverty, homelessness, crime, and violence.

By and large, national research on this topic points to local governments as the true drivers of any “defund the police” reform efforts. In other words, the people with the power to make decisions on how police departments operate and how much funding they receive lies solely with local officials. City councils across the United States–not the Congress or the state legislature— have the power to lead these reforms. This is a tremendous opportunity and one that comes with an immense responsibility to get it right. As a policy advisor to the Bridgeport City Council President Aidee Nieves I saw an opportunity to apply the PDIA methodology I learned in this course to addressing the police problem in Bridgeport.

A recent survey of city councils across the country currently leading local policy efforts to “defund the police” yielded a few important similarities to Bridgeport. First, police departments in these cities accounted for at least one-third of municipal budgets and general fund expenditures. Second, despite annual cuts or flat-funding to public health, social services, and education departments, police budgets in these cities have continued to see year-after-year increases. Third, all these cities have experienced fatal police shootings that sparked community protests.

Given the newness of this phenomenon (the first public calls to “defund the police” occurred less than a year ago), the policies under consideration below are not yet in the implementation stage. In fact, many have changed in the months since being proposed due to the capability limitations of local governments and the political climates of each respective community. Below are some proposed policy reforms by city councils across America in response to “defund the police” demands.

Austin (Texas) City Council

- Remove funding from the upcoming year’s City budget for hiring additional Austin Police Department officers or acquiring equipment like beanbag rounds, rubber bullets and tear gas.

- Eliminate vacant positions in the police department that are unlikely to be filled within a year and reallocate funding for those positions to social services, including mental health and housing stability programs.

- Set a goal of zero racial disparities in traffic stops and arrests.

- Prohibit the use of chokeholds and no-knock warrants and reduce the use of militarized equipment by Austin Police Department.

Seattle (Washington) City Council:

- Reduction in police budget of at least 50% and redirecting those funds to social services and community organizations.

- Increased funding for youth services and employment for at-risk teens.

- Permanently ban the use of “weapons of war” at protests, including tear gas, rubber bullets and pepper spray and reviewing crowd management policies.

- Require officers to always have body cameras turned on or face disciplinary action.

Oakland (California) City Council

- Reduction in police budget of at least 50% and redirecting those funds to social services and community organizations doing violence prevention.

- Implementation of other public safety measures in place of policing. One of the measures that Oakland has previously funded is a group called Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland or MACRO for short. MACRO is an alternative to a police response for mental health challenges.

- Oakland already has one of the strongest Civilian Review Boards/Police Commissions in the country. Passed in 2016, Measure LL (citywide referendum) gave local civilians unprecedented oversight power over the Oakland Police Department.

Minneapolis (Minnesota) City Council

- Pursuing a city charter revision via citywide referendum to eliminate the existing Minneapolis Police Department and create a new city department called the Department of Community Safety and Violence Prevention.

- This department would have responsibility for “public safety services prioritizing a holistic, public health-oriented approach.”

- The city could keep a much smaller division of law enforcement in effect under the supervision of the Department of Community Safety and Violence Prevention.

- The director of this department would be nominated by the Mayor and approved by the City Council. The director would have non-law enforcement experience in community safety services, including but not limited to public health and/or restorative justice approaches.

The problem with these approaches, as I came to learn through this course, is that they start with solutions and in some cases fail to directly address the root cause of police violence in their cities. For example, one popular “defund the police” proposal embraced early on by several progressive city councils was the concept of applying a flat percentage reduction to their police department budgets and committing those funds to education, social service, or health departments. It is essentially a blind flat tax against police departments—a blunt instrument that can appease activists but likely will do little to solve the problems the protests were about in the first place.

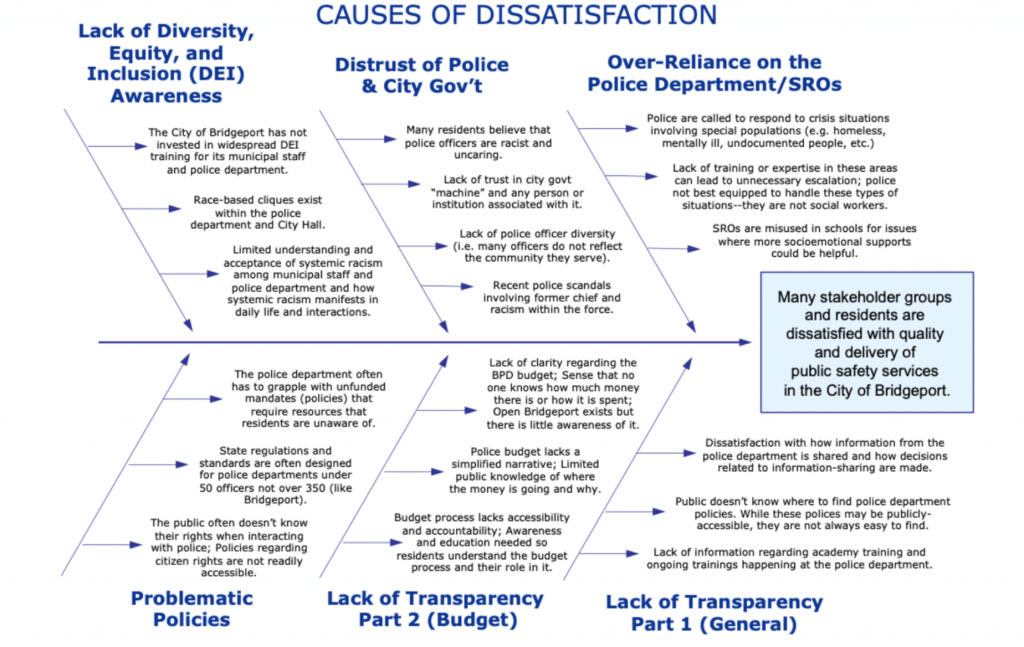

In Bridgeport, the PDIA approach was intriguing to the City Council President and, later on, other stakeholders because of its focus on the root causes of the police problem and the radical concept that local problems have local solutions. Despite many delays, starts and stops, we were finally able to launch a PDIA team in Bridgeport in November focused on addressing the problem of police violence. The team is a diverse cross-section of Bridgeport stakeholders (i.e., uniformed police officers, ‘defund the police’ activists, municipal staff, social service leaders, and local elected officials). I have attached a press release that details the composition and goals of the team. We have had three meetings (iterations) and already revised our fishbone twice. See below for the latest version of the Bridgeport fishbone.

When I signed up for this course, I thought this class was going to be similar to others I have taken at HKS. I would learn the “Harvard way” from policy experts and then go back to my community and fix things. I honestly did not expect to learn the PDIA approach, an approach which is completely counter-intuitive to how I seen and practiced policymaking throughout my career. We are taught through our experiences in the field that the best ideas to local problems are called “national best practices” and that is what I thought I would learn in this class. I found the PDIA principle of local problems having local solutions a bit jarring at first. Policymaking, unfortunately, does not prioritize learning from local people who are on the front lines battling these problems every day. The real and best answers to our local problems are supposed to come from other cities that have tried new ideas and been successful. The idea that we stand to learn more from local people than from smart outsiders is truly radical. Through PDIA, we in Bridgeport have learned to look inward and ask the right questions to the right people in our community.

The prevalence of the “best practices” belief made me initially skeptical that this approach would work. I had to convince myself and then my colleagues and partners in Bridgeport that PDIA was worth investing in. As this class comes to a close, I am taking away a few learnings from this course:

- Assembling a random group of people is not a team. Teaming must be approached with intentionality and teams must be nourished through trust-building and the celebration of wins regardless of the size.

- Leadership means being open-minded and acknowledging that you don’t know everything. A strong leader recognizes and investigates her biases in order to reach a shared understanding with others on solutions.

- Leadership requires you to build a public narrative about yourself and your work. Don’t let others define you and your most important work and accomplishments.

- The people implementing a given policy are the most important stakeholder group when searching for effective and actionable solutions to your problem.

- Burnout is “a problem with the company, not the individual” and you have permission to feel burnout without questioning your commitment to your values and causes. I struggled with burnout this year and kept blaming myself. Why have I stopped caring about people and communities I love and who need help? The HBR article and podcast on burnout was eye-opening and put things into perspective for me during a very challenging time in my career.

- Local problems have local solutions. I wish I could write this 100 times. This is the greatest learning I am taking away from this course. Thank you!

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2020. These are their learning journey stories.

Learn more about the Implementing Public Policy (IPP) Community of Practice and visit the course website to apply.