Guest blog by Khaled Emam, Tim Freeman, Sergii Telenyk, Anupama Thekkinkat Vadukkoot

When we started our PDIA journey in the first week of the spring term, we knew little about the rollercoaster of learning that we were about to board. Although we come from different parts of the world, study distinct fields, and work in distinct professions, we were equally intrigued by the ‘Access to Space’ theme. Every twist of the rollercoaster–from reading technical legal procedures of the UN to speculation of the future of space travel–was worth traveling.

Navigating the Maze: Unravelling the Challenge through Learning

PDIA warrants a profound understanding about the problem context. In our professional lives, we tend to have some training or experience in the subject. At the start of the semester, however, we realized there was a gap between our experience and the needs of the problem construction.

Over the course of the PDIA process, our authorizer turned out to be the most helpful resource. He guided us with the problem from his experience and his organization’s perspective. He even took initiative in connecting us with other experts. This was crucial in determining our deliverables over the very short period.

Yet, we struggled. We knew there was a problem, but the problem did not seem to directly impact the lives of Saudi citizens. The connection to Saudi’s national development plans were tenuous at best. This was the main reason why our problem construction took longer than we expected. We attempted to define the problem tangibly, bouncing between the problem of Saudi Arabia’s launch capabilities and the problem of outdated space laws for two weeks. Hence, we reviewed and revised, and arrived at the manageable problem of Saudi Arabia’s capacities in international space legislation, thanks to immense support and guidance from Matt, Salimah and Abdullah.

The struggle did not end there, as deconstruction needed more information and we were far from experts in the field. The space sector was small, and Saudi was still an emerging player. There were only a handful of people and research papers we could depend on. The method we adopted was to identify specific questions and find people who could answer them. For example, a specific question on space capability can be answered by a space professional or expert sitting in UNOOSA or USA or India. Similarly, a question on bilateral intricacies can be answered by a diplomat in the Middle East.

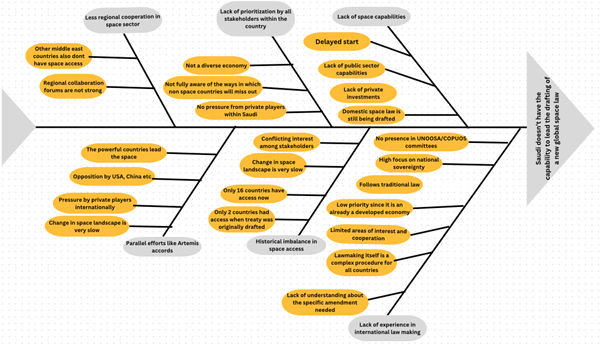

This approach fetched results and we culminated this effort in a fish-bone diagram given below. It may be imperfect or incomplete but we had a bridge to our solution in the form of this diagram.

AAA analysis of these causes turned out to be an eye opener for us. We started the whole exercise under the premise that ‘the space faring countries act in space’ and ‘the rest watch’. Soon, we were impressed to see the areas where Saudi had high authority, acceptance and ability to execute tasks, especially in matters concerning internal priorities and regional cooperation. They just needed to act at the appropriate time in these arenas. We also realized the potential of a diplomatic platform that Saudi Arabia could create for the sector which could act as a springboard for many space aspiring nations ahead. This latent potentiality motivated us to frame our entry points and ideas around these capabilities.

Ideation also posed a challenge. We started by pooling our individual ideas and we were surprised to see that we did not have 8 different ideas. Having common ideas increased our confidence in the practicality of the chosen entry points. Some of our ideas paved the way to more nuanced ideas. We started with six but we iterated and narrowed down to three, but with more detailing and clear milestones. This was a stage where we attempted to learn more about the place of Saudi Arabia in the multilateral space.

Another crucial step we had to undertake was to iterate or plan for iteration. Our ideas could be tackled only with small steps, over a longer term than most others and this limited any avenue for practical iteration process.

The epiphany of problem solving: Insights and unknowns…

Policy makers are often carried away by the urge to arrive at a quick and impressive solution–one that is too often disconnected from the local context. The heavy emphasis that the course lays on Problem Construction was a major revelation. All of us were reminded of the occasions in our professional lives when we thought we had a solution, but it did not solve the problem idiosyncrasies.

In this journey, the ‘unknowns’ outnumbered the ‘knowns’. Instead of marching towards the solution based on the few ‘knowns’, we embraced the process of discovery to learn more about the unknowns. We wished to generate “active knowledge” about what policy concerns were a common concern among countries and which countries would be most willing to push forward a resolution at the UNOOSA. Existing research with the authorizer was able to narrow down potential areas of regulation (mining, militarization, and debris), but only action steps forward would reveal which issues would garner political support.

The magic of an enlarging fishbone diagram not only allowed for careful examination of each component, but also aided us with a deeper understanding of the complexity, context and underlying factors. These factors also point to the specific needs of the organization, the beneficiaries, the context or the solution itself. Thus, a fishbone is both a tool and an opportunity for organizational change.

Iteration was a concept we were introduced to, but unfortunately, the problem we were attempting to solve did not give us enough opportunities to simulate iterations for learning purposes. Instead, we build iterations into the strategy moving forward to turn more ‘unknowns’ into ‘knowns’. The steps forward in this case were about learning rather than about tangible policy. The emphasis on continuous reflection, stocktaking and iterative adaptation clicked with us immediately.

The course helped us understand the essential ingredients to ‘teaming’ where the interplay of the team members’ energy is more important than the individual skills and roles. Our journey in problem construction showed the self-reinforcing interplay between strong teaming and tangible, worthwhile problems.

Passing the baton..

In 1516, Sir Thomas More wrote in Utopia about the problems of policy making, saying, “And it will fall out as in a complication of diseases, that by applying a remedy to one sore, you will provoke another; and that which removes the one ill symptom produces others.”

The challenge we face today is to find ways to go beyond catchphrases about accelerating learning and decision-making. We need practical tools to help us comprehend complexity, develop better operational policies, and implement effective change. PDIA is a methodology that can help get things done in complex systems under the condition of ambiguity.

Wise people say that there are a thousand ways to reach the top of the mountain. However, PDIA is not the only approach to solving problems in uncertain situations. While some issues may be resolved on their own over time or by chance, these situations are rare exceptions rather than the norm. It is not possible to build an effective and sustainable management system based solely on exceptions and luck. But as tomorrow’s policy makers, we have a responsibility to take the initiative.

PDIA is not a magical solution to fix problems but rather an excellent framework for collaboration in solving problems. Embracing the political supportability and implementation feasibility of problems at the start of the policy making process allows for policy design that is not only better matched to the problem on-the-ground, but also more fitting with reality of making change happen in the real world. The PDIA process requires patience, it raises eyebrows, it demands convincing, but it gives the joy of understanding a problem at greater depth than desk research. Our group will enjoy lifelong lessons of collaboration, teaming and learning-through-action thanks to this course.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2024. These are their learning journey stories.