Guest blog by Chelsea Hayman, IPP 2021

Initially, I signed up for the Implementing Public Policy (IPP) Online course with the hopes to help my department secure more sustainable funding for our regular operations. Several other Directors within our agency have been under the constraints of a rapidly depleting federal grant from over a decade ago, stretched thin for resources that were limited when the initial award was made. I quickly found that philanthropic and private organizations have no interest in funding the state government to continue operating. I worked with a specific program facing funding concerns, bringing their issues to private sector investors, who were only interested in selling us their products.

Although the work we do is critical to ensuring the voices of people with disabilities are at the table, the budget we submit annually to the legislature doesn’t involve increases beyond the routine cost of living expenses for employees and existing programs. Having not completed a public policy course in the past, I was not sure what I would learn from IPP. Still, I knew that it would be helpful to have a knowledge base to grow our department’s budget and business opportunities with partner state agencies.

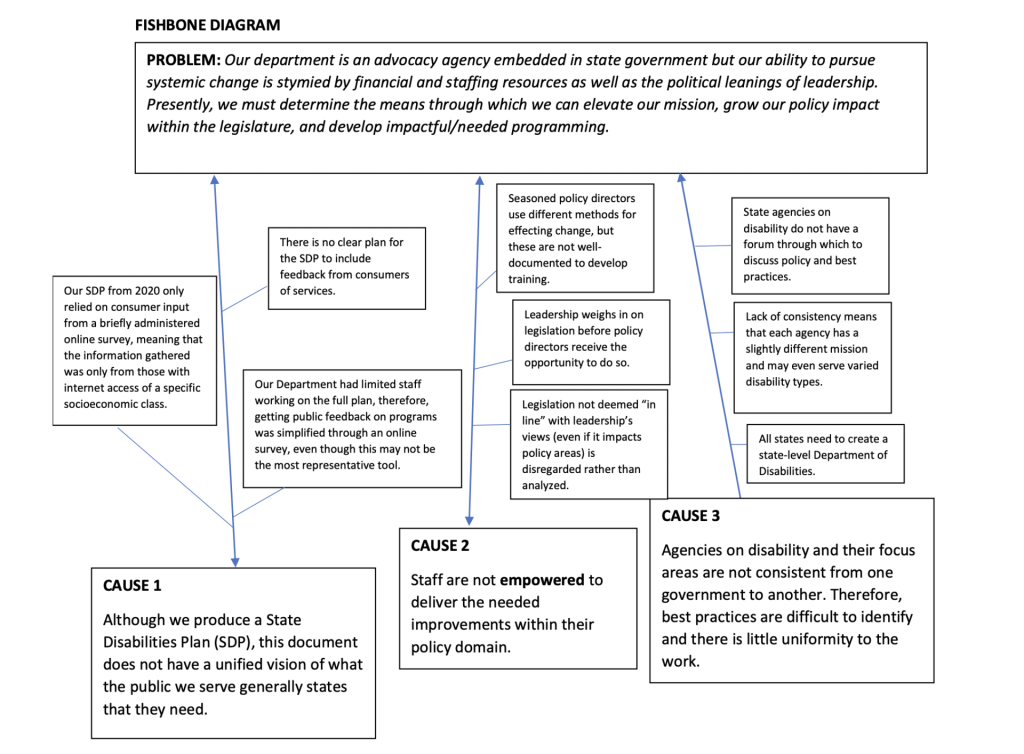

My key takeaway from this course is that is important to get at the root cause of the problem as a starting point for producing successful outcomes. My initial perspective drove me to believe that this was a funding issue, but it was truly a structural issue with how our department conducts its activities. I realized that we were not accounting for best practices within other agencies, critically looking at how we can be better advocates for the population that we support and understanding how we are situated within the larger ecosystem of state governments.

The implementation challenge I am working on is multi-faceted systems change that involves both the elevation of our mission to the state legislature through more advocacy for specific departmental legislation as well as identifying best practices for the agency to follow. I believe that the combination of approaches to restructuring our department will drive up our funding as our programs grow and impact becomes more measurable from a legislative perspective.

Interestingly, when I started elevating these issues to authorizers within our department, some started to spearhead change by focusing on departmental legislation that addresses gaps in services experienced by people with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through conversations with authorizers, I was able to identify that we had limited structured means for interacting with other state governments that house advocacy departments for people with disabilities. This prompted me to identify that additional research on my Implementation Challenge was needed, therefore, I am convening my first meeting of several state governments next week. I have identified several of the state agency contacts that are counterparts to the work we do in Maryland and invited them to convene to discuss what we do, best practices, and how we can work together better to target much-needed federal resources. I am hoping that this will spawn a series of ongoing meetings and partnerships on federal grant applications, hopefully leading us to work with other states on joint requests for funding and culling together resources.

Throughout this process, I have been motivated to better understand how to make my colleagues more engaged in the work of government as a proactive rather than reactive entity. It is sometimes easier to approach problems by focusing too much on the solution we assume will take place. What I have learned through this work is that we need to get a better grasp on the actual problem and all its elements before we get to the solution, our final destination. The journey is where value is derived. It is also where actual changes to policies and procedures can effectively take place. Most importantly, we discover that the process may take much longer than anticipated because a problem’s ancillary components contain beneficial lessons that strengthen our work along the way.

The PDIA Toolkit will become a reference tool for the work that I continue to do to improve our department’s position within the state government. I have incorporated much of what I have learned in the course through my strategy for change management and check back to the lessons from week to week to identify new approaches to acquiring new information or different aspects of the issue. Other PDIA practitioners must become comfortable with the idea that the journey is the final destination. PDIA is not about solving the problem that you believe you’re setting out to solve. It is about better understanding the problem’s component parts to tackle them in smaller doses, making the process much more manageable for the practitioner. Bureaucrats thrive on plan and control but PDIA forces the government into the unfamiliar and necessary territory, so practitioners must be comfortable with these travels and explicitly name them as such when interacting with colleagues. When my colleagues asked, “Why?” I became much more comfortable simply stating, “I don’t know!” which came off better as an exclamation than a statement because it was indicative of the passion I developed for this work even as I am still (and likely will always be) on this journey.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in 2021. These are their learning journey stories.