written by Matt Andrews

Tacit knowledge is an important focal point of my work. I think that many reforms fail because they try to transfer formal, codified knowledge only; when the key knowledge we need in governments and in the development process is tacit–knowledge that cannot be easily communicated in writing or even in words but that resides in our heads and organizations and helps us adapt to the unexpected and navigate the un-navigable.

The Problem Driven Iterative Adaption (PDIA) approach is designed to expand tacit knowledge as part of the development process. “But,” someone recently asked me, “what is tacit knowledge and how do you build it?”

Great question. And this weekend I read a fantastic article that helps me describe what tacit knowledge is and how it is built. The article centered on ‘The Knowledge: London’s Legendary Test for Taxi Drivers” (written by Jody Rosen in the New York Times Magazine). It starts with the following (a bit long for this blog but please read it…it’s great):

At 10 past 6 on a January morning a couple of winters ago, a 35-year-old man named Matt McCabe stepped out of his house in the town of Kenley, England, got on his Piaggio X8 motor scooter, and started driving north. McCabe’s destination was Stour Road, a small street in a desolate patch of East London, 20 miles from his suburban home. He began his journey by following the A23, a major thruway connecting London with its southern outskirts, whose origins are thought to be ancient: For several miles the road follows the straight line of the Roman causeway that stretched from London to Brighton. McCabe exited the A23 in the South London neighborhood of Streatham and made his way through the streets, arriving, about 20 minutes after he set out, at an intersection officially called Windrush Square but still referred to by locals, and on most maps, as Brixton Oval. There, McCabe faced a decision: how to plot his route across the River Thames. Should he proceed more or less straight north and take London Bridge, or bear right into Coldharbour Lane and head for “the pipe,” the Rotherhithe Tunnel, which snakes under the Thames two miles downriver?

“At first I thought I’d go for London Bridge,” McCabe said later. “Go straight up Brixton Road to Kennington Park Road and then work my line over. I knew that I could make my life a lot easier, to not have to waste brainpower thinking about little roads — doing left-rights, left-rights. And then once I’d get over London Bridge, it’d be a quick trip: I’d work it up to Bethnal Green Road, Old Ford Road, and boom-boom-boom, I’m there. It’s a no-brainer. But no. I was thinking about the traffic, about everyone going to the City at that hour of the morning. I thought, ‘What can I do to skirt central London?’ That was my key decision point. I didn’t want to sit in the traffic lights. So I decided to take Coldharbour Lane and head for the pipe.”

McCabe turned east on Coldharbour Lane, wending through the neighborhoods of Peckham and Bermondsey before reaching the tunnel. He emerged on the far side of the Thames in Limehouse, and from there his three-mile-long trip followed a zigzagging path northeast. “I came out of the tunnel and went forward into Yorkshire Road,” he told me. “I went right into Salmon Lane. Left into Rhodeswell Road, right into Turners Road. I went right into St. Paul’s Way, left into Burdett Road, right into Mile End Road. Left Tredegar Square. I went right Morgan Street, left Coborn Road, right into Tredegar Road. That gave me a forward into Wick Lane, a right into Monier Road, right into Smeed Road — and we’re there. Left into Stour Road.”

I liked this description of a man managing his way around London because it shows the blend of tacit knowledge and other, more formal, knowledge. The formal knowledge is what McCabe refers to when thinking about the map of London. He can look at it and see multiple routes from his start to his end point. But this knowledge has its limits. It doesn’t extend to know-how about when streets are most busy, or if locals call a street one thing when the map calls it another, or where the best fish and chips shop is en route… These things are tacit, things one learns by taking multiple routes multiple times and getting an imprint on one’s mind about what to expect, when and where… and what to do about what to expect… because one has been there before.

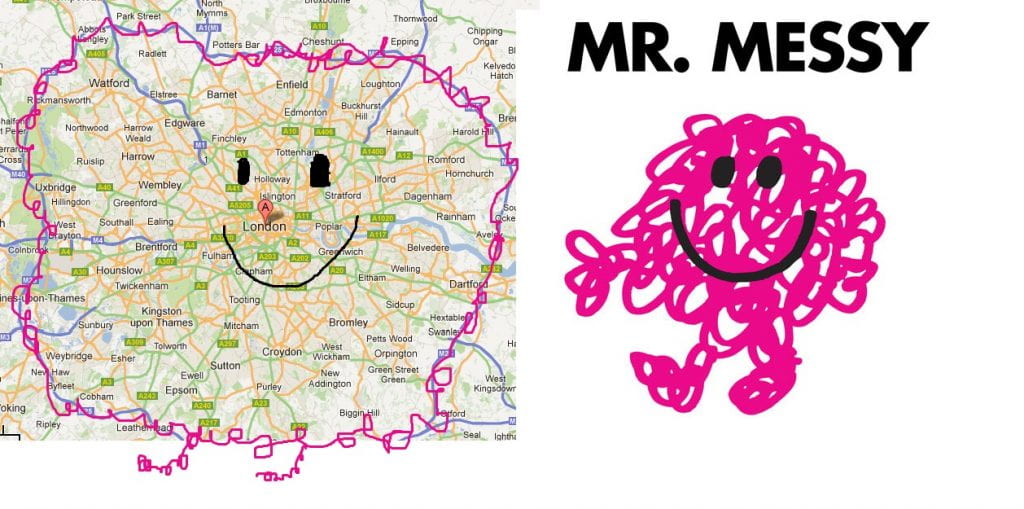

This kind of tacit knowledge is what London taxi drivers are apparently taught in ‘The Knowledge’–a multi-year testing process that requires drivers learning how to navigate the formal map and real-world grit and granularity of London. The tacit knowledge these drivers must build–where I use ‘tacit knowledge’ given Michael Polanyi’s work in Personal Knowledge, 1958–is attained not by sitting in a room learning from someone. No: It cannot be learned this way, given that it is hard to verbalize, or to codify.

Instead, it must be earned, through actually going and seeing and touching and riding and engaging the streets of London…again and again and again. The ‘Knowledge Boys and Girls’ build this tacit knowledge over many years by riding around London on bicycles and motorbikes in a process called ‘pointing’–where they observe granular details of everything, memorizing details that most would take for granted but that are key to any adaptation they might need to make if a London rain storm starts unexpectedly, or if a lorry jams a key road, or if a passenger finds they urgently need to stop en route to see a doctor or buy flowers for a jilted lover!

The details are hard to pass onto others partly because they are so voluminous, partly because they might seem mundane, and partly because they become taken-for-granted in the taxi drivers head. But these details are the kind of knowledge that separate the taxi drivers who can adapt from those who cannot… the ones who know how to zig and zag past obstacles or towards uncertain destinations.

PDIA processes work much like the Knowledge Tests, and require that folks in governments undergoing reform work actively together doing the mundane and repetitive things that make up most days of work and life; stopping regularly to make mental notes of the unspoken lessons they are learning; doing similar things again…learning again….and storing the information about what they did. The process is arduous to some, and unnecessary to others who think that change should never involve recreating the wheel and is best done by getting external consultants to introduce a tried-and-tested external best practice and train locals in how to use such. As I wrote a few weeks ago, however, I think one always needs the process of doing, learning and adapting even if one does not reproduce the wheel… because those who use the wheel need the tacit knowledge built from finding and fitting to make it work.

I believe that doing this kind of learning in groups is a possible way of inculcating the tacit knowledge in the DNA of organizations and not just the heads of individuals. It is a challenging prospect indeed, but I have seen enough of this learning in practice to think–with no hesitation–that it is key to development…the fundamental way of making sense of the complexity, uncertainty and senselessness of much we encounter in governments and societies struggling to progress. Consider the following from the New York Times article…where I replace mention of ‘London’ or ‘town’ with ‘development’…and which emphasizes the role of ‘The Knowledge’ (or process of acquiring both formal and tacit know-how):

[Development] bewilders even its lifelong residents. [Those in developing countries] are “a population lost in [their] own [system].” [Development’s] labyrinthine roadways are a symbol — and, perhaps, a cause — of the fatalism that hangs like a pea-soup fog over [development’s] consciousness. Facing the dizzying infinitude of streets, your mind turns darkly to thoughts of finitude: to the time that is flying, the minutes you are running late for your doctor’s appointment, the hours ticking by, never to be retrieved, on the proverbial Big Clock, the one even bigger than Big Ben. You can see it every day in Primrose Hill and Clapham, in Golders Green and Kentish Town, in Deptford and Dalston. A nervous man, an anxious woman, scanning the horizon for a recognizable landmark, searching for a street sign, silently wondering “Where am I?” — a geographical question that grades gloomily into an existential one. Which is where the Knowledge [and tacit knowledge learning processes] comes in. It is [Development’s] weird solution to the riddle of itself, a training program whose graduates are both transit workers and Gnostics: chauffeurs taught by the government to know the unknowable.”

How often do development interventions provide such a training program?

Development is like London… “a mess: a preposterously complex tangle of veins and capillaries, the cardiovascular system of a monster.” You need to build tacit knowledge to navigate such system… by doing and learning and doing again…