Guest blog written by Lili Vessereau, Boris Houenou, Daniel Saka Mbumba, Daksh Baheti

We are a team at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), enrolled in the Problem Driven Interactive Adaptation (PDIA) course taught by Professor Matt Andrews and Ms. Salimah Samji at HKS. As a team of development and policy practitioners, during Spring 2024, we used the PDIA framework to unpeel the economic growth problem in the city of Laramie, Wyoming.

Our investigation into the problem revealed that the lack of high-paying white-collar jobs hinders Laramie to retain the talent cultivated by this college town, that the lack of affordable housing is discouraging investors from creating opportunities for high-paying employment, and that insufficient tax revenue continue to impede the city’s ability to invest in housing and other development projects. We identified that the city of Laramie is caught in a self-restricting cycle, driven by the relentless pursuit of compact, sustainable development in contrast to rapid and sprawling growth.

Working with The Wyoming Business Council (our authorizer), and a host of other stakeholders, we broke down the economic growth problem into multiple-parts, including approaching it as issues around workforce, infrastructure and collaboration. Our journey also highlighted the importance of both creating collective traction around the importance of the problem and fostering a psychologically safe environment conducive to its resolution. This blog highlights our reflection on the PDIA process, our insights vis-a-vis the problem, and our two cents to the practitioners of this process.

People, Process, and Perspectives

Within the team, trust is paramount because one needs to leverage everyone’s strengths, which means the work will not be equally distributed for each iteration. Trust and respect also facilitates more effective discussions, with the assurance that individuals have conducted thorough research and are receptive to alternative ideas. Consequently, team members are inclined towards engaging in constructive dialogues, recognizing the value placed on their opinions. This fosters a culture where individuals are not dismissive of each other’s ideas but rather seek to understand different perspectives, enhancing creativity within the team and leading to the exploration of a broader spectrum of solutions.

People are your best assets–they know more than is documented. Each person that we spoke to had something valuable to add either to the richness of the problem or to the potential entry points. By systematically speaking to more people–both in the absolute number and the diversity of stakeholders– the group was able to simultaneously increase the richness of inquiry and sharpen the focus of inquiry around the issues.

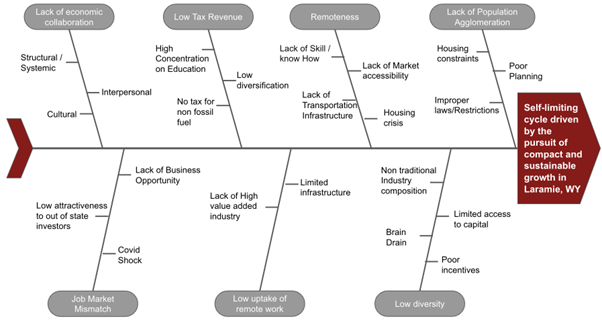

Following an iterative process and leveraging the PDIA tool enabled us to break complexity down. Teams are incredibly resourceful in face of any problems, as long as there is traction. PDIA is a lived testimony to the internal latent capabilities of people who are experiencing the problem and the powerful fluidity to a solution that connecting stakeholders leads to. Tools like the Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram and the 5 whys are a great resource in both organizing and communicating thoughts and ideas.

Uncertainty is a constant in the PDIA process. One of the most intimidating aspects of this approach is undoubtedly the inherent uncertainty it implies. The iterative nature of addressing complex problems means that the time frame for finding a solution is unpredictable, and there are no hard-coded guarantees regarding the outcomes. This uncertainty can be challenging to manage, both from a logistical perspective and in terms of setting and managing stakeholders’ expectations. After all, convincing people to try something when one is not certain of the outcome is hard. However, embracing this uncertainty and the iterative process it necessitates is essential for truly tackling complex issues in a comprehensive manner.

Finally, understanding realistically our perspective as designers is of paramount importance. Addressing unknown complex problems has taught us the critical importance of resisting the temptation to jump right into one’s favorite set of solutions. Such an approach can be narrow-minded, treating only the symptoms of a problem rather than its root causes. We learned that complex problems often come from multiple and sometimes intertwined causes and that addressing one superficially may leave the real problem unresolved and can create new, unforeseen challenges.

Unpeeling the complexity of economic growth: decoding the past, informing the future

After conversing with a few stakeholders, we realized that the original construction of the problem – as a lack of collaboration – was too narrow and did not address the underlying issues. Using insights from data and narratives from the ground, we pivoted to the broader issue of a self-limiting growth cycle, while retaining collaboration as one of the subcauses. This initial step was vital, and ensured that we fully understood and internalized the breadth and depth of the issue at hand. Using quantitative and qualitative evidence, we came up with the following fish-bone diagram, highlighting the multi-faceted causes of the self-limiting growth cycle.

Building on this rich fish-bone diagram, we started to brainstorm about potential entry points into the sub-causes, within the team and with external stakeholders. We made a conscious effort to inquire about ground realities, and to iteratively diagnose each branch. We did this by leveraging our position as ‘outsiders’ – asking simple and innocent questions to advance our understanding and convincing our authorizer of the relevance of our approach.

For example, within the lack of collaboration branch, our diagnosis revealed that the supply of collaborative platforms was not the issue. This led us to dive deep into why existing platforms might not be efficient in achieving collaborative outcomes, and what could be done to rectify this. We followed a similar process for the other branches – loosely based on the keep asking why approach – with the aim to move beyond the surface level to a more ingrained understanding of the issues. To us, this was akin to peeling an onion—with each layer revealing more complexity and depth. Being receptive to unexpected discoveries and willing to explore diverse viewpoints was crucial in gaining a more comprehensive understanding of our problem.

Another early and key realization for us was that we were not the first to tackle this issue, and neither will we be the last. In our conversations, we heard that challenges around workforce, infrastructure and collaboration have been a recurring issue for the city of Laramie. What was missing though was what the city could learn – from its own past, from its peers, and from global good practices. From the beginning, we focused on understanding what the city (and other places which face such issues) has done in the past and why it might not have worked. Such gap analyses, we believe, have the potential to guide and shape potential solutions to the city’s issues.

Trusting the PDIA Journey: Our insights into embracing continuous learning

Trusting the process is essential. When engaging PDIA, trust the process of continuous learning and adaptation. PDIA teaches breaking down complex challenges into manageable components, iterating on solutions, and remaining flexible in your approach. Shortcuts may appear appealing, but they do more harm in the long term. Taking the time to reflect as a team – even a five minute sharing of thoughts and brainstorming – helped us both finetune our ideas and realize the mistakes we were making. It allowed us to be more creative by building on each other’s intuition, rather than working in silos. Consensus building is a natural part of the PDIA process, helping bridge differences and building on commonalities.

Every piece of idea is worth an appreciation of the person who proposes it. This is why diversity in a team is precious and should be leveraged. In the process of problem deconstruction, it is important to make space for all ideas around why the problem is and what underlying causes are. However, engaging and providing data, stories and narratives arguments is what makes an idea stick on the fish bone. In the midst of making a case for each other’s idea, an appreciation for the team member who ideates them is paramount.

Don’t be afraid to question your authorizer and interlocutors. PDIA as a framework is a learning journey, but the process itself – regardless of the context – is about uncovering a bit more of the problem everyday. Asking your questions candidly will, thanks to your outsider’s perspective, enable your interlocutor to understand your perspective better, and be open to either refine their own understanding of the process or share more of their expertise on the problem.

Finally, PDIA is a people-centric process. The size and number of problems to tackle does not remove the very human aspect of this process. Appreciation and fun are two fuels of the whole human experience that PDIA enables. Making that case, here is a montage of pictures highlighting the fun we had in undertaking the PDIA process in Laramie, Wyoming.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2024. These are their learning journey stories.