Guest blog by Miriam Gastélum Aispuro

When I got accepted for the IPP Harvard Program, I was happy relief. I thought, “WOW,” we will finally have the answers to the problems we are trying to solve in the Foundation. The course started and after weeks of learning, discussions and lectures, I realized that my thoughts were wrong and that no institution, professor, or practitioner has a magic wand to solve any social problem, especially when we live in such a complex and diverse world.

Although the relief I had when I received the acceptance letter wore off very quickly; today, being part of the IPP Program has been an incredible journey. These months have given me various techniques to analyze a problem better and face it from different points of view. But not only that, but it has also been a journey full of personal learning that has given me the tools to be a better colleague, leader, and person.

Among the practical tools of the program are topics related to self-care, teamwork, delegating, and leadership. These soft skills are essential when implementing a change in public policy. In my experience, these tools are not a priority when implementing a change in public policy. In practice, the important thing is to report numbers that allow us to justify our work and not necessarily seek a systemic change in the problems we face; not only that, we must do it quickly.

As we learned in the course, understanding a problem requires weeks of analysis, conversations with various actors, and teamwork to be clear if we face a complicated or complex problem. In practice, many of the problems we face are complex, which is when skills such as those taught through PDIA are indispensable.

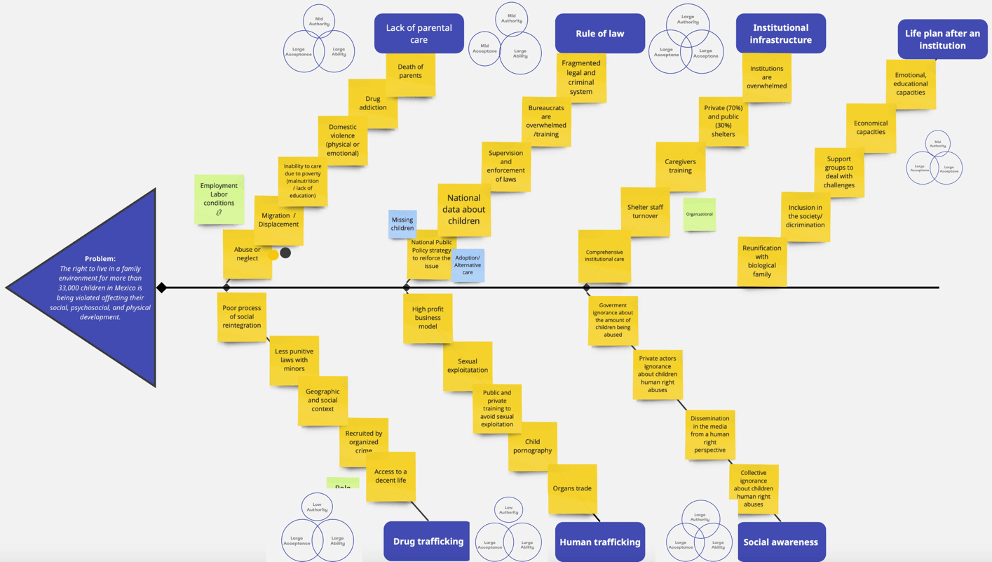

Once we returned from campus, I decided to change the challenge I was working on in The Program. The main reason was that I realized I could maximize the techniques we learned on campus with the challenges we had at the Foundation; Promoting child development by improving care quality in public and private institutions.

Child development is among the various causes that concern us at Fundacion Coppel, especially those children whose fundamental human rights are in danger. Children living in institutions are a historically affected population group, condemned to a future with emotional, educational, professional, and economic challenges, limiting their development opportunities. One of the factors associated with this problem is their care conditions since they were babies.

In Mexico, being a caregiver in a public or private institution is complex. There are many hours of work; the remuneration is the minimum wage and the socio-emotional requirement to care for children who have suffered situations of violence, trauma, and abandonment is very demanding. In this sense, Mexican caregivers’ have a similar profile; primary education (middle school) or high school, no previous experience working with children, and changing jobs is a joint decision aspect that can maximize the trauma of abandonment of many of these children.

Currently, Mexican authorities do not check or demand specific requirements to be a caregiver who cares for a child living in an institution. One of the iterations we did in the Foundation for the problem was the generation of a training model for caregivers who work in public and private institutions in the state of Sinaloa, a unique and pioneering program at the national level. Currently, two other Mexican states of the republic are interested in replicating it. This small victory was thanks to the collaboration and teamwork of actors from different institutions. However, it was also at the beginning one of the great difficulties since the various sectors of the country were involved; academia, government, and civil society.

The authorization process was a management and lobbying process that took months, but being a Foundation facilitated the rapprochement with all the actors involved, always taking into account our role and actively listening to the concerns and needs of those who operate the programs. When we arrived with the highest authority, we already had the authorizations of the operators, with whom we found allies and made an extended team, which is one of the great lessons of PDIA. If a public policy is perfectly designed, but when it comes

to implementing it, it is not functional, then the design process is useless. We must involve those who are operating; they are the ones who are going to implement the changes that are being sought or not.

When a problem is complex, it is essential to have the skills to recognize that roaming through the initiative is not going to solve the problem systemically. We must constantly push and, generate iterations and, look for entry points to generate small but constant changes. In this sense, the PDIA methodology is very flexible, practical, and innovative since it will enable you to return to constantly the problem of building and deconstructing it, understanding that there are factors you do not know and will come out as you generate iterations.

To my fellow active PDIA practitioners, value taking care of yourself and your team by promoting psychological safety environments. Remember to be patient and constant. When we address social problems, we seek to generate massive structural changes as quickly as possible, but the practice is far from that romantic idea. Celebrate the small victories, deconstruct the problem constantly, iterate through various solutions, do not stop, and be consistent because, as Professor Matt said, “little is better than nothing.”

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2022. These are their learning journey stories.