Guest blog by Hanna Harris, Arjariitta Heikkinen, Tiina Hörkkö, Satu Järvenkallas, Katja Nissinen, Piia Pelimanni, Mari Väistö, Meri Virta.

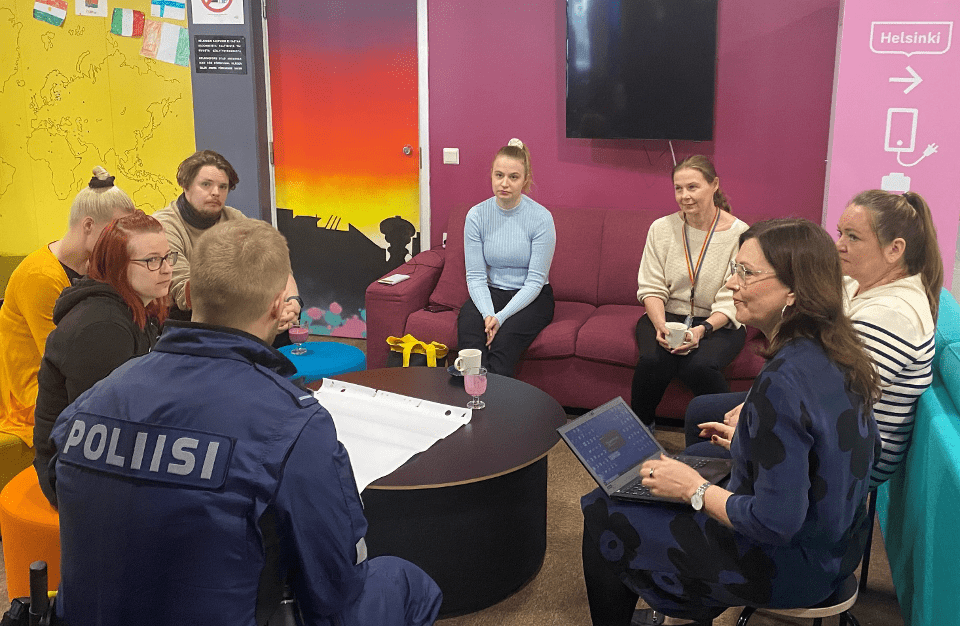

The challenge we decided to take on was improving children and young people’s experience of safety in urban environments. The problem was tackled by a core team of eight people representing each division of the City of Helsinki as well as the Preventive Policing Unit of the Helsinki Police Department. They are joined by a team of forty people representing internal and external cooperation partners of the City of Helsinki.

Helsinki is one of the safest cities in the world. However, there are local differences between different neighbourhoods in children and young people’s experiences of safety, and the sense of insecurity has been on the rise, as indicated by the results of the Finnish national School Health Promotion Study and as reported by professionals working with children and young people, among other things.

Through the programme, we sought above all to find solutions for preventative work, as well as operating models for intervening in problems, in collaboration with various professionals and local operators.

We decided to study the phenomenon more closely in one of Helsinki’s ‘suburban regeneration areas’ and even more specifically in one district, namely Kannelmäki in Northern Helsinki. The suburban regeneration areas are areas where the City of Helsinki will particularly invest in development, infill construction and increasing attractiveness in the coming years. The aim is to prevent the city districts from becoming segregated.

From the start, our goal was also to be able to apply the lessons learned and solutions developed in this project to other areas of Helsinki, primarily the other suburban regeneration areas.

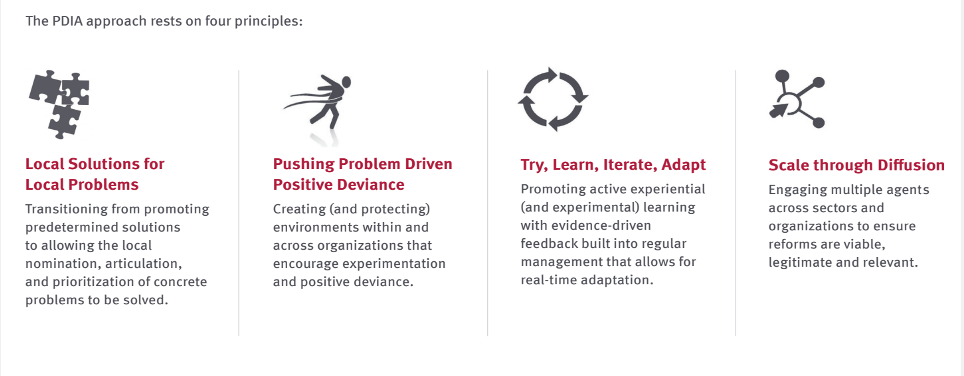

Our work has been strongly guided by the Problem Driven Iterative Adaption (PDIA) approach developed by Harvard University.

We started by considering the definition of safety and ended up using a broader term, the experience of safety, as it covers both the physical aspects of safety related to the urban structure and the social aspects.

As the experience of safety is a very complex problem, cooperation between various actors is needed to resolve it.

We have been working on a broad scale from the outset, involving various operators, and we have held regular meetings with an expanded team of experts and managers, among others.

Small Steps Towards Safe Neighbourhoods

Based on a root cause analysis of the problem, we selected three approaches through which we took measures: providing safe and meaningful leisure time, improving the safety of public spaces and better interaction with multicultural residents in services.

One objective has been to strengthen the participation of children and young people and the role of families in the city services. Often, children and young people who make others feel insecure are precisely those who themselves also experience insecurity.

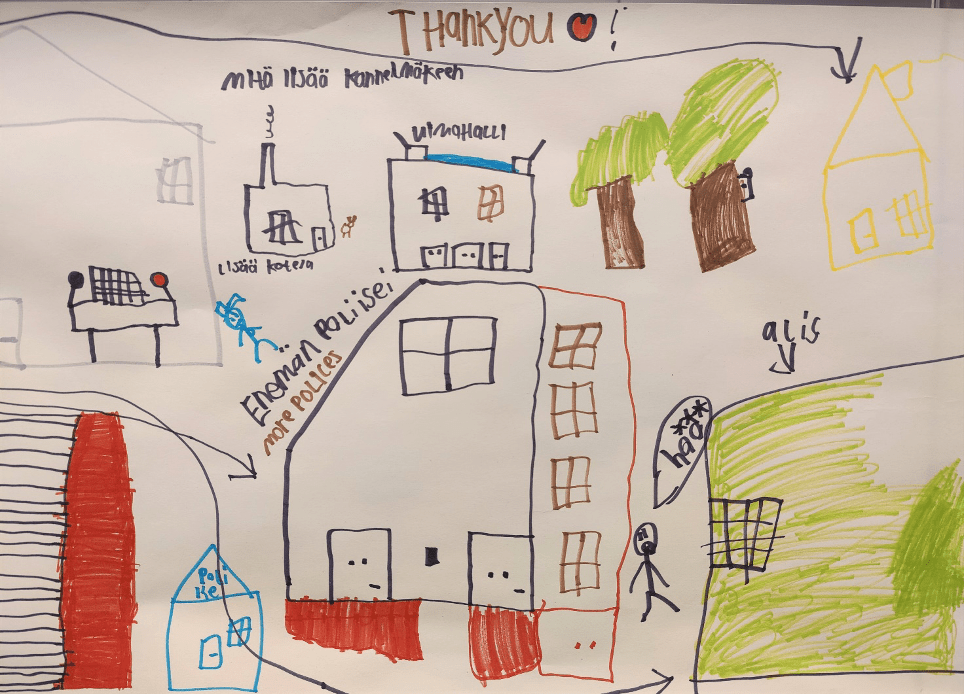

Kannelmäki Comprehensive School has been actively involved in the work and organised low-threshold events in addition to official parents’ evenings to reach a larger group of parents. A safety walk with children and young people will also be included in the school’s school year programme. Upcoming placemaking experiments carried out together with local children have provided input directly from the children for concrete improvements in the urban environment, such as changes to Sitra Square, which people find to be unsafe. Targeted recreational activities and hobbies are now offered to children and young people in the area through a new service. Cooperation between the school, youth services and the police has intensified further, and new operating models and operating models found to be effective elsewhere are now being tested in Kannelmäki.

In addition to these measures, we outlined a bigger objective: to strengthen the local phenomenon-based leadership model. As a result of this work, areas and neighbourhoods have become more important, and the significance of local leadership is highlighted in responding to local problems.

Based on our improved understanding, our team made a public value statement: “We will tackle young people feeling increasingly unsafe in public spaces and experiencing a lack of belonging in their community.” Enabling a safe and welcoming environment for children throughout the day is good for each individual and the community.

You Have to Stop and Think About The Problem

When tackling the problem, it was essential for us to at first take the time to focus on the problem itself, together, instead of jumping straight to potential solutions. This way, the problem also became our shared problem. And when the problem is shared, so are the solutions found for it. The more time we spent considering the problem, the clearer it became that the solution required input from all of us, including the families, communities, and organisations.

The programme has also required us to be transparent about the progress and to continuously consult new people. We have shared very unfinished ideas and sought feedback on them widely from various stakeholders.

We have taken the user-centred and human-centred approach seriously in the work. The City of Helsinki is familiar with this approach from the use of design in the development of different services and processes but combining this perspective with a phenomenon-based challenge has taken the work forward. Time and again, we have asked – and questioned – whether we have defined, with sufficient weight, the problem together with those who are most affected by it: children and young people, families and those working with them.

The experience of insecurity is an example of a phenomenon that can occur at a very localised level in the city.

Since we chose to focus on one city district, namely Kannelmäki, the programme has led us to the question: what is the capacity of the City’s divisions to react to local phenomena and how can we manage local phenomena more effectively together?

Had we not narrowed down the area precisely, we would not have been given the impetus to take further steps in the review of the ‘local phenomenon-based leadership model’, which has proved to be an opportunity to also create cooperation models for application in other parts of the city.

United by a Common Problem

The key to finding solutions has been good cooperation and mutual trust between the members of the core team. This has led to people being committed to their work and feeling that the atmosphere allows them to openly throw out ideas.

Cooperation has increased, particularly among those working in the area. Cooperation is not anything new in the area, but the fact that the guidance comes from supervisors who share a common view of what the measures should achieve makes cooperation more efficient. The problem, challenges and solutions have become increasingly shared, and the area is characterised by warm cooperation. When we work more together, our dreams of what should change become increasingly shared.

This approach also assures us that, when tackling the problem, we must find the key persons who identify the operating models already in place, the operators responsible for coming up with a solution and the operators that are able to carry out the selected measures.

It is amazing how the wheels have started to turn in such a short amount of time, extending to and combining a wide variety of functions. People have had a desire to participate. Discussions with various professionals have sparked eureka moments. Various organisations have found their role in supporting the common goal. The fact that the members of the core team have the power to decide on resources has enhanced the activities in the area.

The programme has been good practice for all of us on how to approach the management of phenomena in a large organisation. To keep up with these phenomena in the future, we must work together.

What did we learn from all of this?

We learned many lessons from the programme that we can use in other projects in the future. The programme has done a great job of combining practical work and the demonstration of progress with systems thinking. This should serve as the guideline in comprehensive management.

In addition, we have noticed how important it is to break the problem down into manageable pieces and stop at regular intervals to think about what we have learned so far and what, based on these lessons, we must seek to change in our work.

The approach helps us see the big picture more broadly and increases our understanding of who is responsible for coming up with a solution or who can help with it. Thanks to this approach, the problem is not as challenging as it initially appears.

The Collaboration Track cooperation model commits different operators to work on solutions to complex problems identified together. This process can be used to produce content for things such as service solutions that consider local characteristics of different areas. The working model is naturally applicable to various content themes.

However, the most important thing is that children and young people have a stronger sense of belonging to the community and access to safe services and public spaces in Kannelmäki.

This is part of a blog series written by city leaders who participated in the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative cross-boundary collaboration track during 2023.