Guest blog by Rasmuss Filips Geks

Back in 2001, something groundbreaking occurred. Seventeen technologists gathered in the Wasatch mountains of Utah to draft the Agile Manifesto. It was a set of principles for IT Project Management that would fundamentally change software development. Today, any user-friendly digital product we use was probably developed using these principles.

In a way, PDIA or Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation is a similar innovation. Rather than software, it offers a concentrated toolkit to address complex public policy challenges. These are problems where the types of potential obstacles are impossible to predict and can’t be solved using a generic Plan and Control approach. Unsurprisingly, the digital transformation of Riga City is indeed a complex challenge and PDIA helped to fundamentally change my approach towards addressing it.

Before I started the course, I had done a full external audit on our digital governance. The audit identified potential solutions that were often unrealistic. Some of them, such as lack of competent IT personnel or lack of data-based decision making, required funding that would never be approved by the city. Other problems, such as our closed IT architecture, outdated e-services, or a monopoly contractor, seemed too complex to even begin addressing.

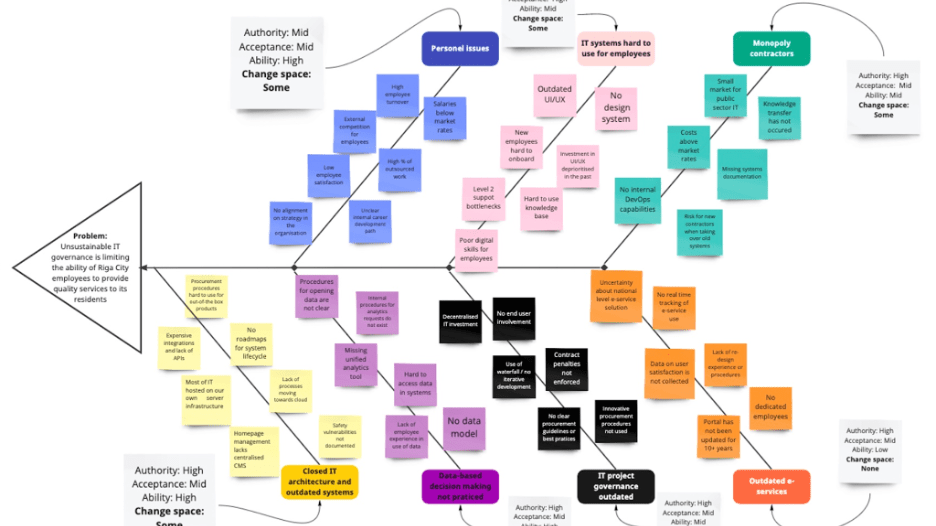

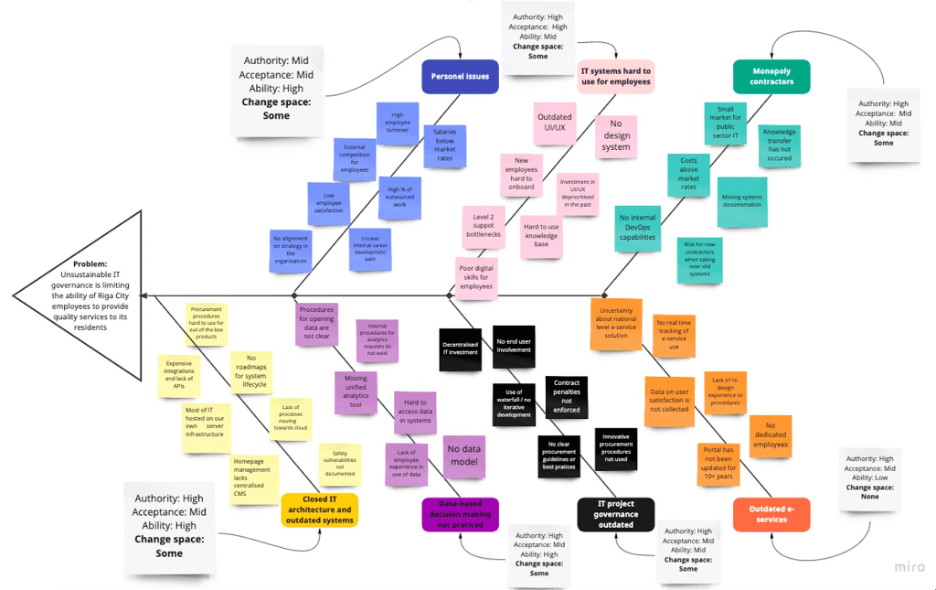

So the first thing I did was root cause analysis using the Fishbone Diagram (see below). It helped me to reevaluate our audit results, try to break down these problems myself, and expose them to criticism from my course colleagues. I was not only able to better understand my core problem statement, but also add dimensions to my problems that I had not considered before.

The next thing I worked on were potential areas where solutions could be tried called change spaces. PDIA requires evaluating three dimensions for every root cause of a problem. Authority explains whether there is approval from decision makers, acceptance evaluates stakeholders and their views on addressing a specific cause, while ability says if capabilities to address a problem are available. If either of these are lacking, then they must be built before a specific cause can be addressed. During the course, I was able to make significant progress on these dimensions for numerous problems.

A good example for building authority is related to data-based decision making. When I started working for the city, Riga hardly used data in our operational governance. For more than a year, I was not able to get any meaningful resources to address the issue. After doing PDIA, I realized that my issue was lack of authority. Even though I had not yet achieved any measurable results, I was able to use key learnings over the previous year to build authority with decision makers. I explained what I had learned about data practices of other cities, the needs of city departments, our data infrastructure, and new data analytics tools. This allowed me to allocate more resources to the problem, thus improving my change space.

Similarly, I realized that I had never thought about acceptance for my challenge at all. I had already implemented changes in our digital governance without involving our employees, which had almost proved destructive during an important internal reorganization. After PDIA, I changed my approach and started bringing in more stakeholders during our planning process. For example, when I heard that a new IT project was getting push-back from our Property Department, I spent a lot of time building acceptance from them. While it took several long planning meetings, I was eventually able to get them on board. Even though their acceptance was not crucial for the project to be implemented, I knew that this allowed me to expand my change space towards building better digital products in the city.

As for ability, I was able to better reflect on where change space was possible and where I had made mistakes in the past. When I started working for the city, I spent the months trying to come up with a strategy for fixing our decentralized website governance. I created a stakeholder working group with weekly meetings. While it seemed that I was engaging stakeholders, I had not realized we did not have internal capabilities to implement solutions we were discussing. Over the next year, none of them were implemented. Because of that, there are some parts of the problems, such as improvement of e-services or closed IT infrastructure, where I am only working on building internal ability. I know that until I can get more internal city capabilities, I will not be able to address any part of these problems.

Once I had understood change spaces, I focused on entry points for action. These are potential solutions that might be able to address part of the problem. PDIA deals with complex problems, so it requires an ability to adjust and change plans based on the outcomes of previous solutions.

A key obstacle for me was figuring out how to implement this approach in the Riga City Administration. In the past, the city would allocate funding for digital projects based on requests from specific departments. Allocation was done at the start of the year, and no changes could be made. Knowledge about PDIA helped me to justify changing this model towards centralized digital project funding. This means that next year, we will be able to implement projects based on an iterative approach.

Lastly, I worked on using my learnings and leads. PDIA teaches that often, potential solutions for problems will fail. They will waste resources and there might not be any tangible results. Because of that, it is important to also measure progress by communicating learnings and leads to maintain your authorization for engagement.

During the course, I started to actively note down insights that I received from people I engaged. A lot of insights came from potential vendors for the city – they shared best practices on how digital governance was done in some of their customers. Other insights came from international partners, who shared how they managed their own digital transformation. Over time, I was able to use these insights during key discussions about digital transformation projects, and they were often crucial towards maintaining my authorization.

Even though it has been more than 20 years, the public sector is still not very versatile in agile software development. But this course helped me to understand that changing how we build software would not be enough. PDIA allowed me to understand the entire process of digital transformation as a complex public policy challenge, and it gave me the tools that I will keep using to address it.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2022. These are their learning journey stories.