Guest blog by Chiedza Juru, Gigi Hui, Michael Bediako, Manuel Sada Vazquez, Therese Wagner

As we found out throughout this course, the challenges faced by the Government of Trinidad and Tobago are many, not least of which is the profound issue of declining tax revenue and generalized tax evasion. While this problem is not new to developing countries, it is clear that no single solution works across the board. Instead, we found ourselves challenged by striking a balance between local solutions and external best practices both cognizant of and adapted to the specific bureaucratic, social, and political dynamics of Trinidad and Tobago.

After 7 weeks of working on the problem, meeting with the team and our authorizer, as well as with key stakeholders on the ground and external resource persons from our own networks, the Tax Force Team identified several key learnings from this course about the PDIA process. Here are our condensed three main findings:

First of all, establishing a team constitution and investing in building a team dynamic is key. Our team saw the results of being intentional about our team constitution from the very beginning. Because of this, we never had to come back to it to adjust our team dynamics. The conversation we had about the constitution was thoughtful and represented the joint principles of the group to such an extent that it was not necessary to refer to it during the course. In this sense, the creation of the team constitution was the first step towards investing in our team dynamics, which were defined within the first couple of weeks. By the end of the course, meetings and assignments were being produced, enriched, and revised seamlessly.

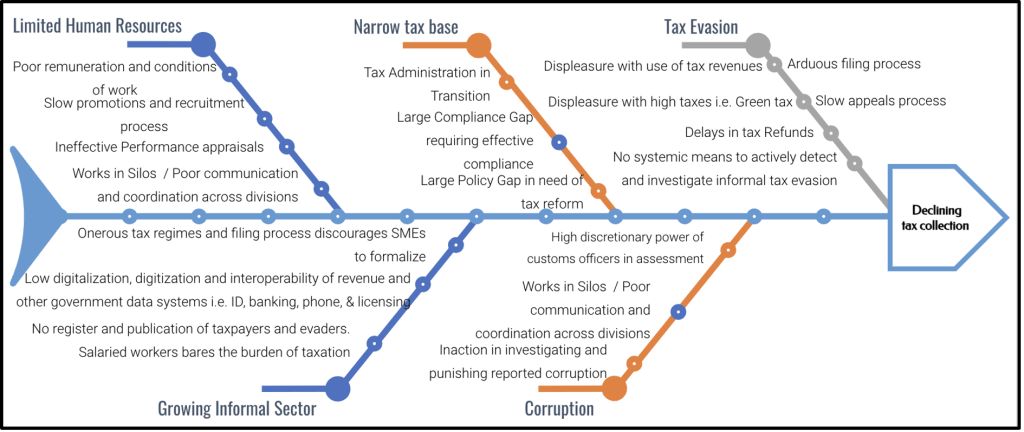

Secondly, we also found that the creation and revision of the fishbone diagram was a major component of the process. For complex environments, focusing on defining rather than solving problems, and having the flexibility to continually adjust your findings, is a must. There are so many moving parts and shifting variables when it comes to macro-level issues that organizing your ideas with the aid of a framework is the only real way to begin making progress.

Finally, there is no replacing the weekly check-in with the authorizer and sharing the team’s work with them. As Prof. Andrews mentioned, authorizers are usually busy, but scheduling a check-in on a constant basis and being efficient with that time is also fundamental to maintaining trust and approval from the people in charge.

In terms of insights and learnings about our problem through this process we found that, like most developing countries, taxation is a deeply entrenched issue in Trinidad and Tobago that requires a multi-stakeholder approach to address its various dimensions and facets, as well as years of political and social investment. This is not, however, an excuse for lack of action or urgency.

Part of that process is generating greater cognizance of the complexity of the problem itself and how differently it is perceived by stakeholders. In the particular case of Trinidad and Tobago, understanding the perspectives of different stakeholders was key due to the political polarization of the topic. Tax reform was already underway through the creation of the new Trinidad and Tobago Revenue Authority (TTRA) and lines had been drawn along political parties regarding the reform. As such, having clarity of the political landscape was fundamental when interacting with stakeholders on both sides of the aisle. Furthermore, accepting and grasping the politicized nature of the issue is the first step to engage with stakeholders in a meaningful manner. This can include acknowledging stakeholders’ concerns, and seeking out ways to address them while keeping them engaged in a process that gradually becomes depoliticized and centered around the issue.

In terms of words of wisdom to share with other students/practitioners of PDIA, we would highlight the importance of the following:

- Focus on developing relationships. A technical understanding of the problem is certainly important, but the ability to develop relationships is just as, if not more, important. In our project, taking advantage of the contacts and understanding of our authorizer was a crucial step every week. The fact that our authorizer opened doors for us was due to the fact that we were able to establish a relationship based on trust and good intentions.

- Lead with the problem, not the solution. This is fundamental when working on complex problems. Investing time in exploring and identifying the problem(s) goes a long way towards learning about the local dynamics and identifying the relevant actors on the ground.

- Be humble. Understanding your knowledge gap when it comes to the issue and the value that local actors and/or experts have is also key. First, to get you up to speed with the situation and to understand the local context. Secondly, being humble provides you space to consider others’ perspectives, opinions, and policy solutions. As was mentioned in class during our last session, often the answers are already available on the ground, they just have not yet reached the authorizer.

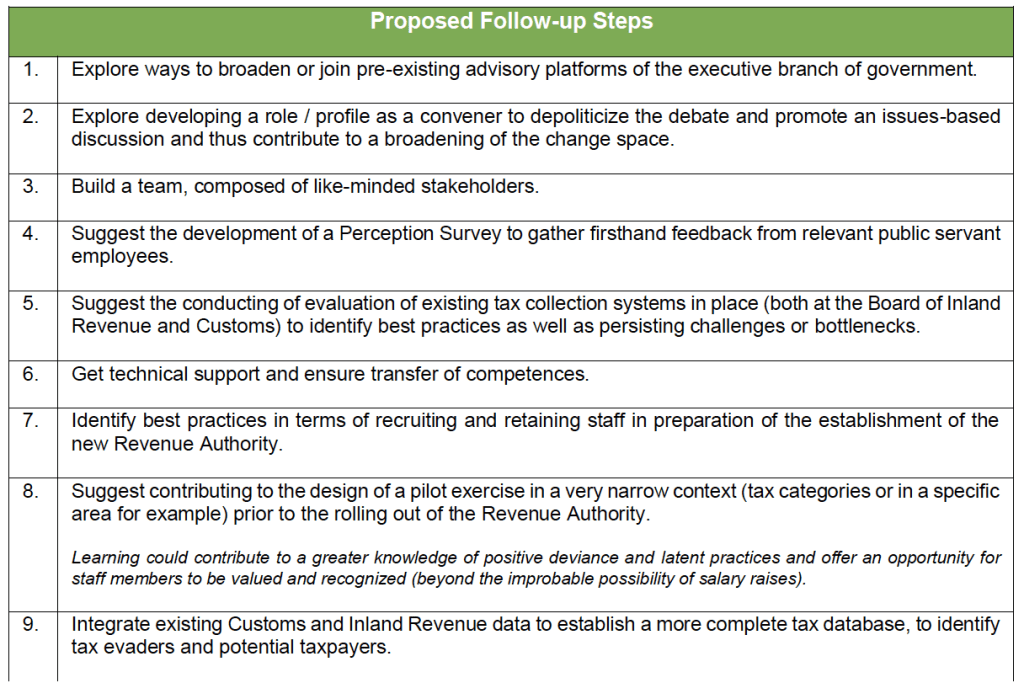

Finally, we discussed with our authorizer the following not exhaustive possible follow-up steps:

Before concluding, we would like to express our gratitude toward our authorizer, without whom we would have not been able to grasp the extent of the problem or move forwards towards considering possible solutions. Thanks again!

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2023. These are their learning journey stories.