written by Matt Andrews

A preamble to my views on Morocco

Earlier this year I wrote a paper and a blog on why African countries struggle to win in global soccer. I argued that teams from these nations seem stuck at middling levels of competitive participation (who they compete against) and rivalry (how often they win).

The main reason, I suggested, was that African teams do not play enough matches against better competitors, which limits their potential to build their competitive capabilities (given that we learn from what we do and learn new things from those who do better than us).

I suggested that African countries have the potential to win but need to ‘play up’ more often to build that potential. Adapting words from Antonio Conte, the former Italian player and current manager of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club, I explain,

“We [in Africa] have a lot of space for improvement, to be a [continent] with aspirations to win. [But] To use the verb ‘to win’ is more simple than winning because to win you have to build something important, be solid … Then you’re ready to win. Otherwise you have to hope.”

Now, what about Morocco?

So, Morocco is now in a World Cup semi-final—recording Africa’s best performance in the tournament to date (with 49 other countries doing worse in prior or current appearances). They did this by beating three top-ten teams (Belgium, Spain, and Portugal), drawing another (Croatia), and overcoming the best qualifier from North America (Canada) in the last few weeks. This pathway to the semis was arguably tougher than those of South Korea and Turkey, who made it—surprisingly—in 2002.

But, using data from the 2010s, my paper showed the nation as having fallen off from its highs in the 1980s (when, in 1986, a golden generation took the country—and Africa—to its first narrowly lost final 16 match against Germany). What’s going on?

A story of growing capabilities

Commentators are linking Morocco’s performance to various things, including the squad’s current quality and the manager’s ingenuity (and the fact that he is from Morocco). I’m not sure of such explanations:

Morocco was ranked 23rd out of 32 coming into this tournament; with an Elo-rating of 1766 (where the Elo-rating captures performance over time as a measure of a team’s demonstrated competitiveness). Carrying a market value of 315 million EUROs, I ranked the team’s recognized playing capabilities as 17th, which was better than its performance and does suggest it had more potential than its historical record. But not a top 4 finish. Based on experience and record, its manager, Walid Regragui, came 27th, hardly what one would expect is needed to make a semi-final (or more).

Given such data, I do not think Morocco’s success is about its static current on-pitch playing capabilities or managerial capabilities (at least not primarily). What I do see, however, is that Morocco came into the 2022 tournament ranked 1st in what I call momentum capability—a belief, based on recent experience, that one can win anything.

I calculate this capability by looking at the 5-year change in a country’s Elo-rating (mentioned above): It was 11% for Morocco, higher than any other nation, reflecting an increase from 1590 in November 2017 to 1766 in November 2022. The 1766 rating was still much lower than Brazil’s global high (of 2195) going into the tournament, but the 11% improvement in ranking was what really stands out.

Factors behind the growing capability

Various factors seem linked to Morocco’s high momentum capability, including an off-pitch shift in scheduling focused on ‘playing up’.

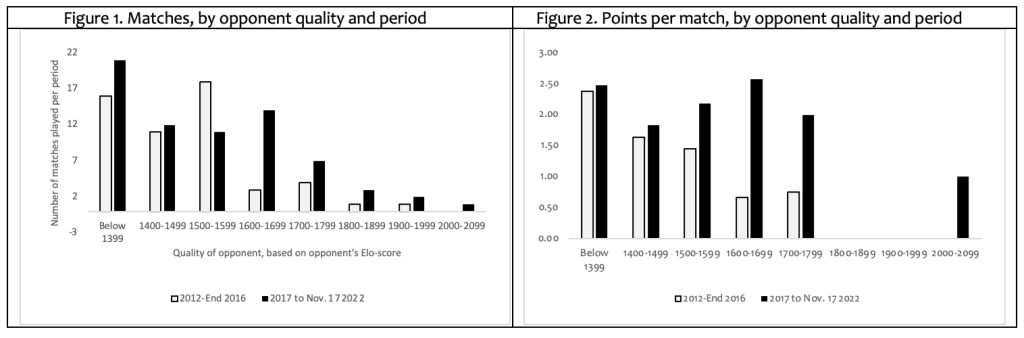

As Figure 1 shows, 83% of the team’s 2012 to 2016 fixtures were against opponents with Elo ratings below 1599 with only 9 opponents were rated above 1600. Between 2017 and November 2022, the team played only 62% of its matches against sub-1599 rated teams and matched up with 27 opponents rated above 1600. Some of Morocco’s higher-quality matches were centered on the 2018 World Cup (where it competed). But the country also played 13 matches against 1600+ rated teams after July 2018. They won 7 of these matches, and drew 4, pointing to a growing penchant for winning big matches against high profile competitors. Figure 2 shows this improved winning record, with Morocco scoring more points per match against every kind of competitor in the 2017-2022 period (as compared with the 2012-2017 period).

I believe that the very act of ‘playing up’ has been key to building Morocco’s capabilities, and is a major reason the country has the momentum capability we see today—the team has learned from playing tougher teams, winning more than before, and developed a confidence that is hard to beat.

I see other sources of capability expansion in this period. First, Morocco had three experienced, winning managers from 2016 to late 2022. Hervé Renard and Vahid Halilhodžić both spent about three years with the team up to July 2022, bringing winning records with them (Renard won the African Cup of Nations in Zambia and Ivory Coast in 2012 and 2015 and Halilhodžić won various club titles in Europe). Regragui followed up on this record in 2022, with a CAF Champions League win with Wydad AC in 2022.

Whereas their legacies vary, the managers fostered a winning mentality and legacy of ‘playing up’ after 2017. Their impact was evident in a string of achievements after 2016, including two quarterfinal and a round-of-16 appearance in the African Cup of Nations (in 2017, 2019, and 2021), two African Nations Championship wins (in 2018 and 2020), and two World Cup Finals tournament qualifications (in 2018 and 2022).

The country has also built its soccer capabilities on the technical side, where we see significant advances in the country’s near-pitch and off-pitch capabilities. This includes the opening, in 2009, of the Mohammed VI Football Academy. This academy has spawned a number of international players in the last decade and a half, including Hamza Mendyl, Nayef Aguerd, Azzedine Ounahi, and the man who scored Morocco’s winning goal in the World Cup quarterfinal against Portugal, Youssef En-Nesyri.

The Mohammed VI Football Complex was also renovated in 2019, creating a modern facility focused on enhancing the national team’s competitiveness. Apart from providing new playing facilities and housing, there was also an emphasis on providing performance management opportunities through the new entity. This includes medical treatments like physiotherapy, stress testing, psychology, podiatry, nutritional medicine, and more. It also includes data analysis, where the complex allowed more tracking, tracing and instructional opportunities than had previously existed.

The team’s data analysis capabilities were further enhanced in 2022, when Chris Van Puyvelde was hired as Technical Director and staff like Moussa El Habchi were also added. Van Puyvelde had played a similar role in Belgium between 2015 and 2018 and was part of the semi-final reaching 2018 World Cup experience. El Habchi had also been with Belgium at the World Cup, as a video analyst, and brought such skills to a team that was already using state-of-the-art analytical methods.

The team was another source of emergent capability in this period. A core of players played in the 2-2 draw and 1-0 loss against Spain and Portugal in the 2018 World Cup, and represented the country in multiple matches afterwards. This kind of shared tacit experience is invaluable when competing. Many of these players come from the country’s diaspora as well, and play in Europe’s top leagues. This is relatively new for Morocco, whose teams in the 2000s were much more likely to be born in Morocco and play in Morocco. Whereas some find the diaspora connection controversial, having players with personal and professional experience across contexts brings all sorts of tacit experience and know-how into the team, and helps establish the kind of capabilities we saw in the country’s run of wins in Qatar.

Lessons?

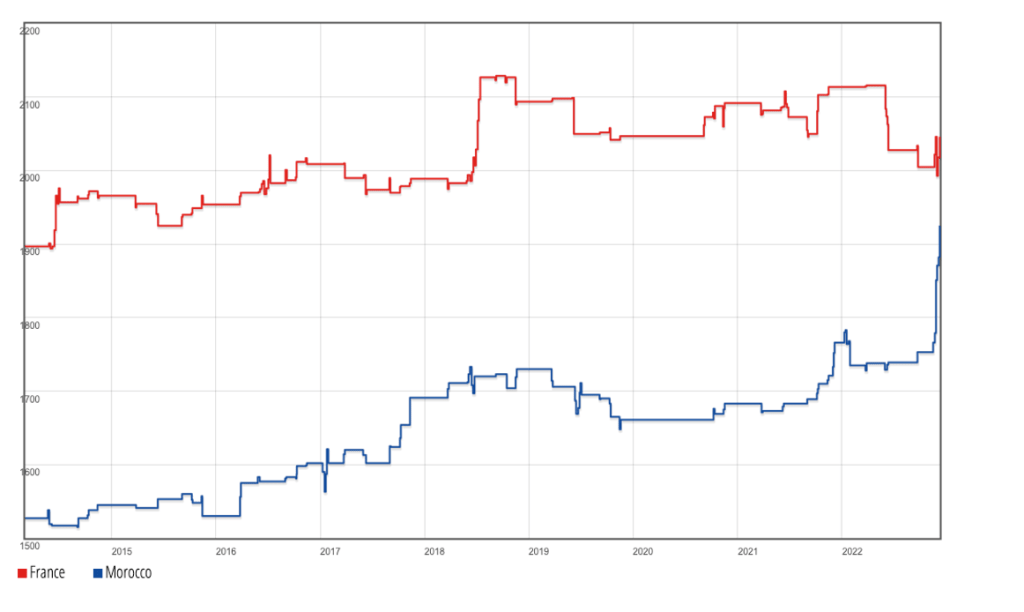

Morocco had less than a 10% historical chance of achieving the World Cup Semi-Final (given that Turkey and South Korea reached this level as sub-20 ranked teams in 2002). Their historical chance of getting to a final is zero. No one has done it and the challenge is significant, shown in the difference between the team’s Elo ratings and those of France (its opponent) in this graph (from international-football.net).

As you see, the French rating (given its past performances) has always been significantly higher than Morocco’s, and even today—the day before their semi-final, Morocco is between 1851 and 1925 (depending on metrics) and France is at 2046.

But the momentum Morocco’s team have is undeniable. You can see it in the way their Elo-score has shot up from mid-1500s to mid 1700s and now into the high 1800s or low 1900s (depending on the entity doing the analysis). This momentum is not flash-in-the-pan stuff. It is built on a foundation of hard work and preparation, through five to fifteen years of playing up, making thoughtful managerial decisions and institutional investments, and building, attracting, and supporting the country’s talent.

The country’s competitive hope has involved more than hoping for a golden generation (which they may have). They have pursued an active strategy of capability building, which has yielded the most dangerous of all capabilities—momentum. I believe this is the most valuable capability one can build in countries that are not yet established as competitive, and this Moroccan team has it in spades.

Who knows how far it can take them, in this tournament and beyond. And who knows how the country’s soccer momentum might translate into an economic momentum capability too?