Guest blog written by Leticia Born, IPP 2021

It took me some time to really understand what PDIA (Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation) is all about. By the end of the IPP Online I was able to expand my thinking beyond having access to useful tools that will support me in identifying realistic ways of thinking about solutions for bottlenecks in policy implementation.

PDIA is about identifying a problem, deconstructing it, understanding the spaces for change, trying out potential solutions, and then coming back, re-thinking the approach, and trying again. However, it’s not about waiting for a year-end report to assess learnings and only then, learn about what went wrong. It’s not about having the conviction that one specific leader or a typical public officer “hero” will find the solution. It’s not about sticking to typical behaviors and beliefs.

PDIA for me is fundamentally about incorporating a new mindset—an “atypical” mindset, I would say. A mindset that is more oriented towards feasibility of real problems and not ideal solutions. It also reminds me that those typical phrases we hear on and off about public policies implementation can be challenged – such as “We need more time to implement a solution!”, “We need more resources to do this!”, “Why do this now if the governor will change next year?” or “The bureaucracy is just impossible to deal with!”. These challenges will remain. But the PDIA mindset supports us in not having them as barriers. It’s possible to try within the contours of public policy.

As a manager in a philanthropic organization working to support civil society organizations that engage directly with public officers and local governments, my goal entering the Implementing Public Policy (IPP) course, was to be able to provide updated tools and possibilities of work for our partners. What happened is that I ended up developing a co-created way to build a potential program for the improvement of early childhood development services in the Peruvian Amazon. In the 14 hours of workshops that I organized with partners, we co-created a theory of change, considering the deconstruction of the problem exercise, as well as the triple-A methodology.

Having those tools worked very well to have an innovation mindset and to really think about the feasibility of what was being proposed, besides reflecting about the Authorizers, and the stakeholders that needed to be engaged in the process. Although I did not apply the iteration processes as recommended in the PDIA approach by the book, my goal was to provide these tools to work with these partners that are implementing projects in the Peruvian Amazon. It will be important to keep this mindset alive during the pilot implementation, and taking stock to assess what went wrong and what needs to be done differently in shorter periods of time. I shared the PDIA check-in tool with partners so that we can monthly assess the struggles, the learnings, and what can be done in the next period.

This way of thinking also helped me recognize and see myself in a leadership role to identify and develop a group of partners, each one with specific abilities and skills, and to find the right type of complementarity – the key to finding solutions for complex policy barriers.

However, it’s not easy to introduce a new way of thinking that is people-driven, to individuals or groups that are not used to it. I experienced a bit of suspicion initially, since the typical way of working is more prone to abiding to rules or the directions of an Authorizer. Once this was understood as a pathway to work together, based on active listening and co-creating, the group moved forward. I learned that in these moments, it is crucial to continue with the approach and to provide confidence in this way of working.

Once you are able to explain why the PDIA way of working is more conducive to change, people will generally find value in it, and will want to spend their time and energy to work towards policy change.

Photo 1: One of the workshops developed using part of the PDIA tools with Peruvian civil society organizations.

Photo 2: One of the exercises developed during the workshops with partners

that was inspired by the Triple-A exercise to establish feasibility.

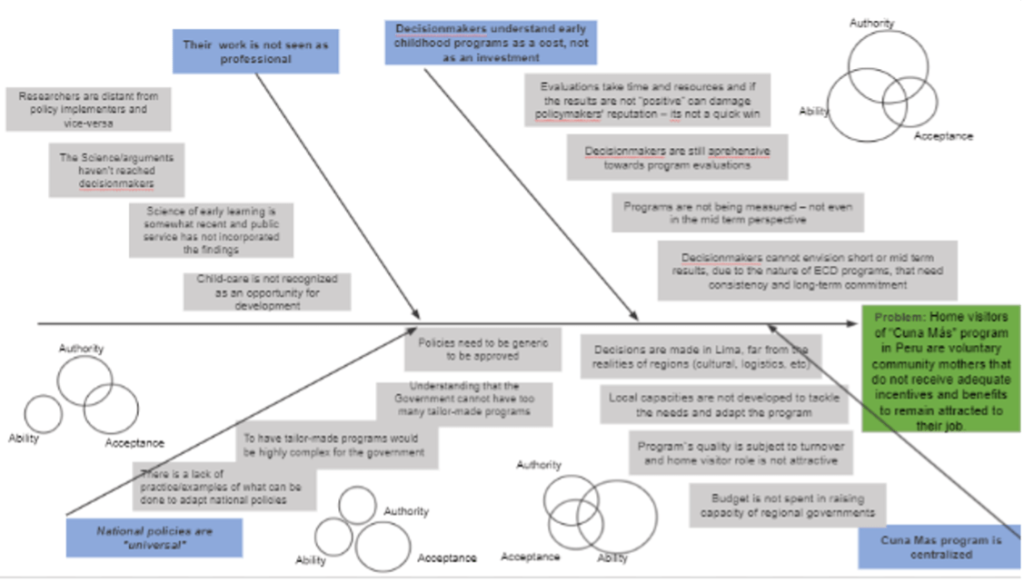

Photo 3: My Fishbone Diagram

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in October 2021. These are their learning journey stories.