Guest blog written by Matthew McNaughton, Gaurav Dutt, Mandy Le Monde, Anjanay Kumar, Yashila Singh

What were some key learnings from this course? (about the PDIA process through addressing your problem)

As we went along the process of PDIA, we learnt a lot about the process of understanding and deconstructing the problem, working in a team and about PDIA itself. A few of these learnings are included below:

Firstly, problem definition is often an underinvested endeavor. PDIA’s methodology for constructing and deconstructing problems, along with the strategic role that a well constructed problem plays in mobilizing actors in the problem space are immensely valuable. Maintaining the discipline to focus on problem definition, instead of jumping to creating solutions can be difficult. Having a team that shares this value can help you to stay on point. Additionally, the starting definition of the problem may really be just a symptom, or it might be someone’s perception of the problem but not really the root cause or shared by other stakeholders. The process of PDIA acknowledges this and emphasizes the importance of spending time to define the problem and socialize it with partners to test and validate your assumptions.

Secondly, it is crucial to have a curious stance towards the problem you’re working on. Our professors emphasized the importance of ‘humility and curiosity’ while trying to understand the problem. Approaching the problem definition through humility and curiosity allowed us to admire the problem and become genuinely interested in it despite not being from the affected region. It also allowed us to resist the urge to jump into thinking about potential solutions before deeply engaging in understanding the problem.

Thirdly, increasingly the likelihood that teams are effective is something that can be systematically done. Taking the time to define the motivations for the individuals, articulating values for the team, and how we want to work together is an important part of building effective teams. It is so easy to skip this step. Writing these things in a Team Constitution allowed us to set the ‘rules of engagement’ within our team and avoid any confusions about ‘who is doing what’.

And lastly, PDIA stresses the importance of taking small consistent steps every week. For us, this meant speaking to at least one new person or reading at least one new document each week to better understand the problem. This continuous engagement facilitated an incremental progress that led to surprising gains in our understanding of the problem, helped to sustain motivation, and generated team accountability. Additionally, weekly team meetings and meetings with the authorizer also allowed us to be on the same page and incorporate feedback. This enabled us to execute and learn at the same time.

What progress did you make or what insights did you gain about your problem through this process?

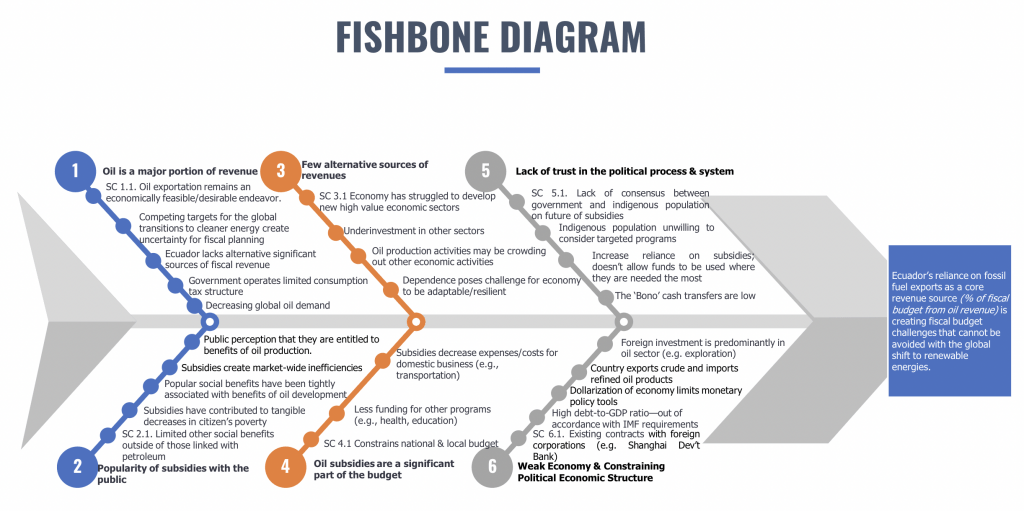

Our perspective and understanding of the problem evolved throughout the course. Initially, we interpreted the problem to revolve around the political economy of Ecuador’s transition away from oil exports, primarily constrained by the political will of key actors and the economic returns to the government’s budget.

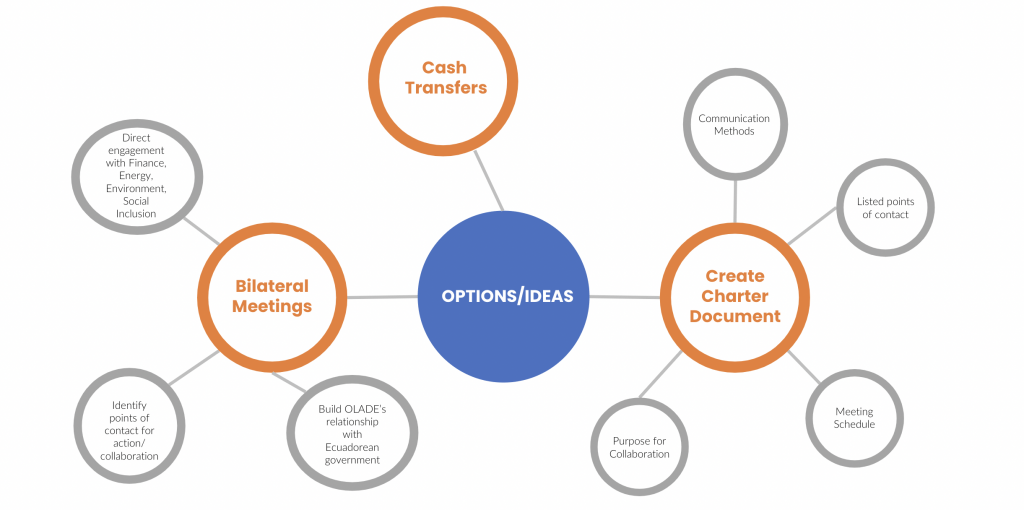

However, further discussions highlighted a diversity of factors, including a significant deficit in trust between the government and the public, the important role that subsidies had played in recent social and economic progress, and the structural imbalance caused by Ecuador’s failure to develop the local capacity to produce refined petroleum products that citizens demanded. In our last few “policy pushes,” we actually zoomed in on coordination challenges among specific government ministries who played an important role in the financial planning process but were not currently en-gaging in effective collaboration. This was a factor that we felt our authorizer was relatively well-positioned to influence and had identified as one of their priorities.

Do you have any words of wisdom to share with other students/practitioners?

Documenting team norms, values, and roles in a team constitution are a surprisingly effective way to build team cohesion. Moreover, when this is paired with a team emphasis on building psychological safety it can help create a resilient holding environment for a team. The PDIA process can be intense, and mistrust and misunderstandings within the team can derail the whole process and distract from doing the actual work. It is, therefore, essential to discuss early on and intentionally build a team culture which values psychological safety and has clearly defined team norms.

Don’t let the seduction of working on “solutions”, derail your progress in understanding the problem you’re working on–you’ll be surprised by how much you can continue to learn throughout the class and the policy process. Everyone can develop solutions and policy proposals, but very few persons engaged in policy work take the time to think critically about which dimension of the problem they are well positioned to execute and whether their proposed solutions are well “fitted”to the context they are operating in.

Taking a learning stance is extremely essential for addressing unknown problems rather than having an ‘expert mindset’ which could potentially hamper the problem construction. Our attitude towards the problem influences how we engage with it.

The difficulty in addressing an unknown problem is not knowing if and when we will reach an appropriate and acceptable solution. This is because due to the iterative process of PDIA it is entirely possible that the problem statement could change four weeks later and that we need to be comfortable with the possibility of that happening. This requires one to be comfortable with uncertainty which may be challenging initially.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2022. These are their learning journey stories.