Guest blog by Loretta Minott

It has been almost twenty years since I graduated from college. At least fifteen years since I have been involved in an instructor-led collegiate level course. As a mother to a toddler, going “back to school” was not in my plan. But I had a superior who believed in my ability and thought this program would be a great opportunity for me to strengthen my resume and add upon my qualifications. Applying to the program was a breeze. I then anxiously waited to find out if I had been accepted. I was overjoyed when I was accepted. I mean, this is Harvard! That joy quickly turned to fear. As I read the professional profiles of those in my cohort, I remember saying out loud “What did I get myself in to?” I mean, who was I? I had a bachelor’s degree from Temple University, an unfinished graduate degree, and I was now in a course with folks who hold PhD’s from some of the most prestigious universities. How would I align with these people? I would shortly find out that everything was going to be just fine. I ended up in a breakout group with some of the most supportive and kind colleagues. We became fast friends and we pushed each other to complete the course in its entirety.

I quickly learned that my expectations of this course were far off. While I was nervous about the reading and the assignments, I could tell that the people that put this course together kept in mind that we were all working adults as well. The readings, while a lot, were not excessive in length. Each reading supported what Professor Andrews lectured weekly. And each lecture was supported by our individual and group assignments. What was nice about our assignments was that we were given a maximum word count to abide by. Concise and clear answers were expected. Assignments were reviewed and feedback was provided that helped to further define our problem statement.

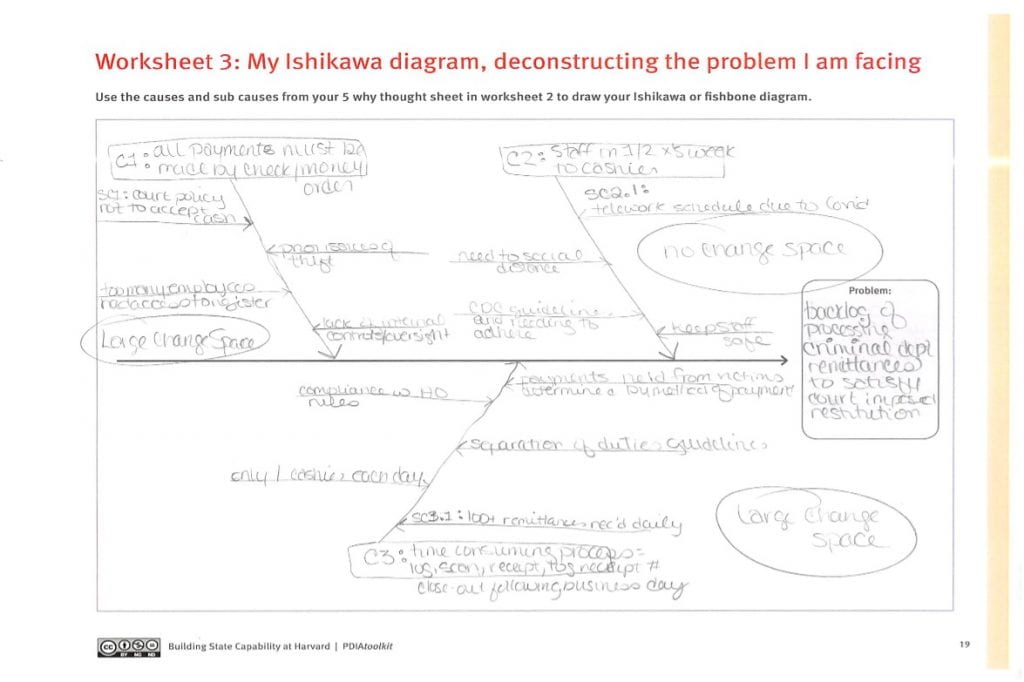

My implementation challenge was to address the backlog of criminal debt payments received by our court. Currently, our court has a “no cash” policy. We also do not accept criminal debt payments electronically. That means, for every defendant who is ordered to provide restitution to their victims, the payment may only be by check, money order, or cashiers check. With over 100 remittances received in our office daily, and a limited in-office schedule due to the global pandemic (Covid 19), our office was behind in receipting and posting payments received by defendants. This meant that victims were not receiving money owed to them quickly. Defendants were in danger of being held in violation for non-payment. Our department discussed ideas to get through the workload – stay late, work on Saturday, more days in the office, etc. None of these were options due to our obligation to follow strict financial policies.

Most of my key learnings came in the beginning of the course. As a newly hired finance supervisor, I was just learning how to work and collaborate with a team that I was now responsible for. There was an initial reading that discussed definitions about leadership in the face of complex challenges:

• Leadership is about taking risks on behalf of something you care about.

• Leadership is about disappointing your own people at a rate they can absorb.

• Leadership is about mobilizing and enabling others to take purposeful risks with you.

Each of these definitions I typed up and placed in my desk to review on those hardest of days.

We learned that implementation may involve multiple agents to advance the implementation:

• Authorizers

• Motivators

• Conveners

• Connectors

• Problem identifiers

• Ideas people

• Operational empowerees

• Implementers

• Resource providers

Why so many people involved? According to Lee Kuan Yew, we should use the metaphor of an orchestra when it comes to describing leadership. “There are multiple functions played by multiple agents in producing orchestral sounds.” A leader can lead a group, but it is the people he includes on the team that are necessary to deal with complex policy challenges. One needs people who have the knowledge, skills, and experiences, for every aspect with a policy challenge. While one leader can authorize change, you may require a separate leader to provide ideas or knowledge of what challenges lie ahead.

Regarding my implementation challenge, I made small progress. While most of the blame can be placed on Covid, the reality is that with so much going on, my implementation challenge was placed on hold until our office returns to a “normal”. We did identify a way to address the challenge of remittance backlog – identify a method, acceptable to the Administrative Office, for criminal debt to be paid electronically. The fishbone diagram below, was created to help identify entry points or areas that we can begin the implementation process. About halfway through the course, I had to review and revise my problem statement. While I thought this would set me back, it was explained that my policy challenge was the answer to my challenge. I had to narrow down the challenge to the main problem. That was fun and the feedback was accepted.

This course gave me the tools necessary to approach change in the future. Each of the week’s assignments contained reading materials that can be utilized at any time. Leadership, which we all strive for, comes with many nuances. It is not always what I say goes. There are staff that, as leaders, we have a responsibility to engage with. Rob Wilkinson’s 4P Model of Leadership emphasizes perception, projection, people, and process. Each one is vital to strategic leadership. When working within the 4P’s we should work on leadership both internally (how we work with ourselves) and externally (how we deal and work with others). Amy Edmondson discussed the two ways of thinking about mobilizing people: teaming and team building. It is important to know the difference between the two. The article Everything Starts with Trust offers a useful way of thinking about building trust. There are three core drivers: authenticity, empathy, and logic. When trust is lost, it can be traced back to one of these three drivers.

My final words of wisdom to share with fellow PDIA practitioners is to not give yourself a set time for implementation. While you can have a goal end date, the reality is that with so many agents involved and unknowns, there will be bumps in your policy implementation. My challenge involved the ultimate unknown which was Covid. This pandemic caused everyone to think about what was most important to their job at this time. Implementing anything new was the last thing that authorizers wanted to deal with when trying to determine how to continue the goals of the court even during the pandemic. Keep striving, keep pushing. If you get a “no” think of a way you can convince your audience to say “yes”.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2020. These are their learning journey stories.