Guest blog by Marcio Paes-Barreto

When I got my first job in the field of economic development I started reading everything I could about it. I started noticing a stark difference in the rationale and methodologies proposed by the books I was reading. After a while it was possible for me to separate what I was going to read (even before I got deep in the book) into two categories: strategy/marketing books and development economics/economics books.

In my professional life I had my fair share of experiences with marketing and the readings of Porter, Kotler and Chernev. So the second category was the one that disappeared quickly as I learned interesting new things from the thoughts of economists like Acemoglu, Mazzucato, Duflo and Moretti. And, of course, from the usual suspects like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Joseph Schumpeter. I felt ready for my first day of work.

Well no plan survives contact with reality. The struggle in the regions I was working with were real and the resources that people had available to deal with their challenges did not seem appropriate. Pre-packed solutions from consultants abounded and nobody seemed to be talking about economics when trying to understand the root cause of their problems. Lucky me. I met a Senator from my region with an economics background and working experience with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), World Bank and the Inter American Development Bank (IDB). There was so much to learn from these experiences.

In order to keep making sense of all this, I reviewed economic development literature looking for best practices. In my research, I found at the IDB website the paper “Smart Development Banks” (Fernández-Arias, Hausmann, Panizza – 2019). This paper put me in touch with innovative minds and novel ways to address perplexing growth issues. By that time I started encountering frameworks and tools that I needed to tackle some of the complex challenges related to economic growth in my region. Then COVID-19 started and I led several “special” projects for a while.

Around the United States, major economic challenges have been met either with investments in infrastructure or with the use of marketing best practices to segment, target and communicate value (assets) of a community. Nothing inherently wrong with that. However, for example, using a SWOT analysis to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of a business to determine which investments to make or what to market is a relatively simple task when compared to doing the same for a region and its economy.

While in economies with significant growth, the prevalent approach relied on the application of development economics and of economic principles to create specific growth-oriented policies and programs. Are marketing-based solutions so common in the USA due to unique economic development challenges? Do we still believe in elaborate versions of “if you build it, they will come”?

It is easy to assume in the richest nation where opportunity abounds and institutions are strong, that a region is in economic distress because of the market failure referred to as “information asymmetry.” Other times the immediate assumption for failure to grow is of missing infrastructure (buildings, industrial parks, etc.). However, these assumptions are not precise enough and proper identification of market failures is not a simple task. Also investments in infrastructure can be ineffective and very costly.

The development story of the United States of America is unique in many ways and can provide more insights into this issue. Previous to the transportation and communication revolutions, the economic challenges of the early American republic (1780-1830) were like the challenges developing countries face today, which, in many cases, can be summarized by people and communities producing goods for their own consumption and / or providing raw materials to others to add value.

However, the investments made around the 1800s in transportation and communication created thousands of miles of new railroads, canals, and telegraph lines opening up the productivity of vast regions of the USA to new markets. After this significant infrastructure build up, rural producers could turn what they produced beyond their own consumption into cash. The new material wealth allowed access to things previously out of reach to improve their lives.

Investments were also made in innovative technologies, productivity increased, and more wealth was generated. This quest for productivity led to an explosion in the number of new patents. Entrepreneurs and the state also developed contractual infrastructure where property rights, labor, equity, and debt rules mitigated investment risks.

“Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things.” – Adam Smith

With these foundations in place and the promise of economic opportunity for all, immigrants from all over the world came to the USA in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The influx of new brains (knowhow – tacit knowledge) and the industrial revolution (tools, machines, and patents – codified knowledge) created a great ecosystem. Businesses flourished everywhere, and continued productivity gains created significant wealth in many regions.

So, if this is the American development story, why is it so hard to replicate? Why are businesses not continuing to flourish everywhere in America? Why are some rural economies struggling? And why does the productivity inequality between the metropolitan areas and rural areas continue to increase?

I was trying to piece all this together and learn about what was being done in the USAID, Harvard’s Growth Lab, and MIT’s development economics practices, but I had mixed results and slow progress.

Things really changed when I attended the course Leading Economic Growth (LEG) at Harvard Kennedy School. The course was co-led by Professors Ricardo Hausmann and Matthew Andrews, with a team from Harvard’s Center for International Development (CID), including members of the Growth Lab and Building State Capability teams.

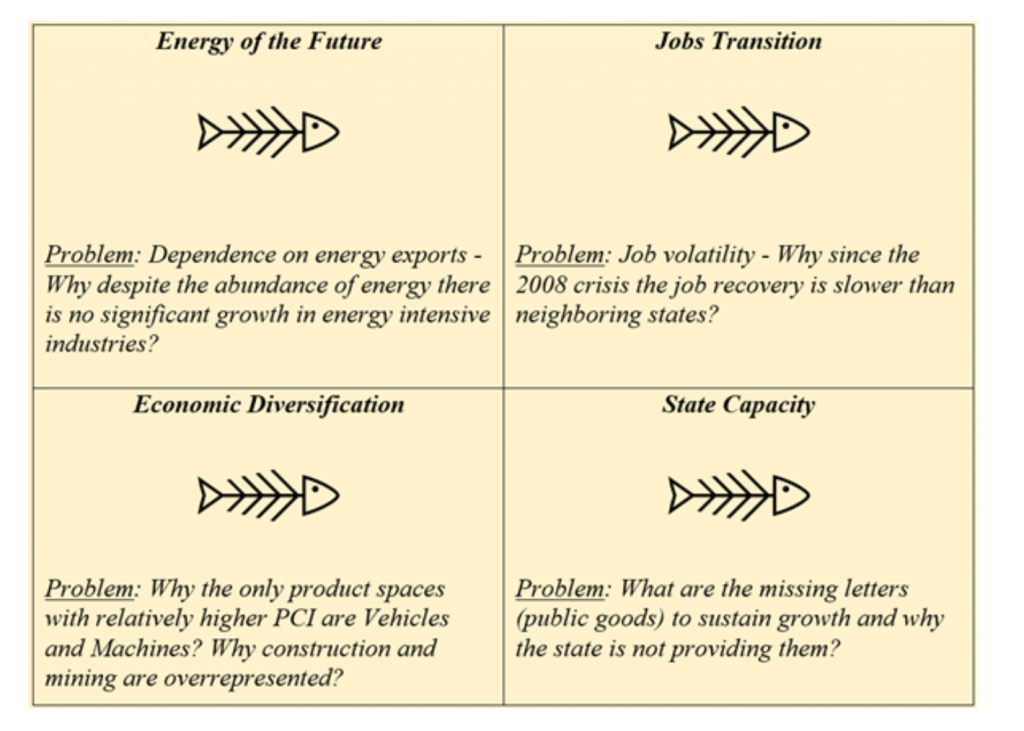

This course organized in a comprehensive and easy way what I needed to analyze Wyoming’s growth process and growth challenges. The course also provided me with a framework to engage entrepreneurs, local governments, and stakeholders in effective ways to find solutions to long lingering economic challenges. It also allowed me to better construct and deconstruct a regional growth challenge and identify what the constraints to growth are, instead of relying on pre-packaged solutions or solutions that are best suited for the private sector.

Here are a few of my takeaways from this learning experience:

· Start with a growth-related problem, ask good questions, build a team, develop solutions, iterate, and keep moving. Harvard’s Building State Capability program calls that approach Problem Driven Iterative Adaptive (PDIA). It is like Agile for economic developers. More information here: PDIA Toolkit

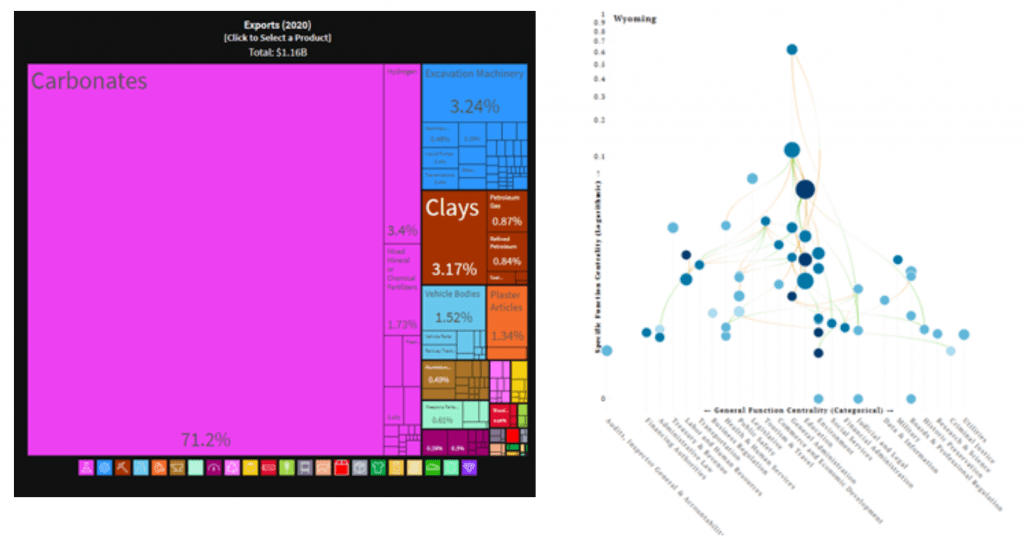

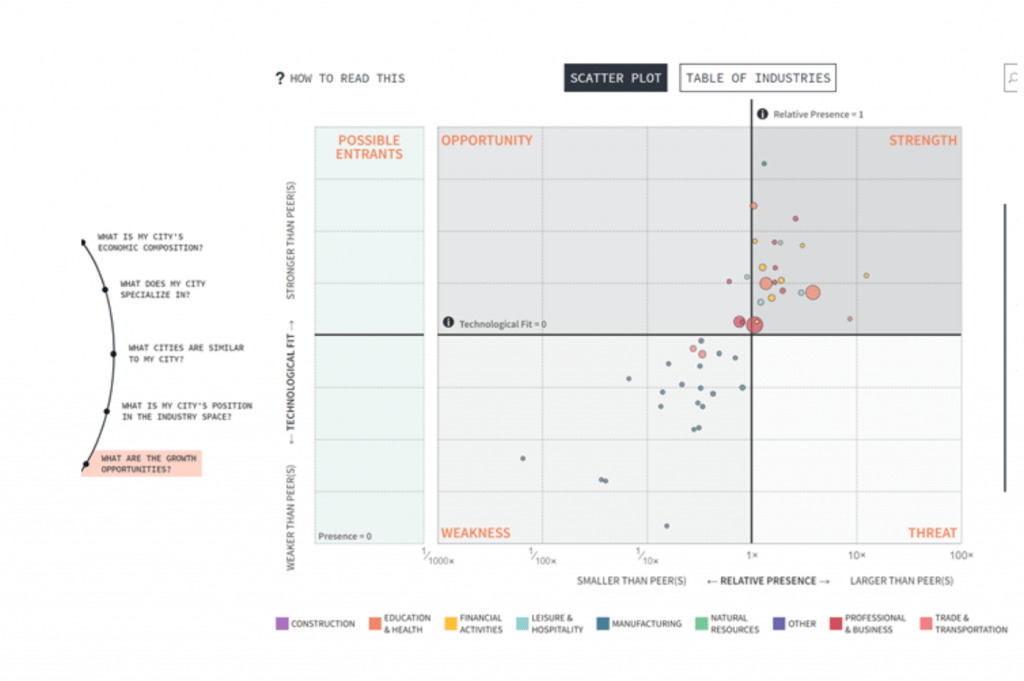

· Development is dependent on productive knowhow and growing your economy depends on increasing it. You can gain insights about your existent productive knowhow using what Harvard’s Growth Lab describes as Product Space. Both Atlas of Economic Complexity, Metroverse and Observatory of Economic Complexity are excellent tools to start understanding your product space and productive knowhow.

· Relevant data and economic models coupled with analytical capability are as important as stakeholder engagement and agility (as in Agile iterations). Integrating the two takeaways described above is crucial to accurately diagnose your growth syndrome and find your growth path.

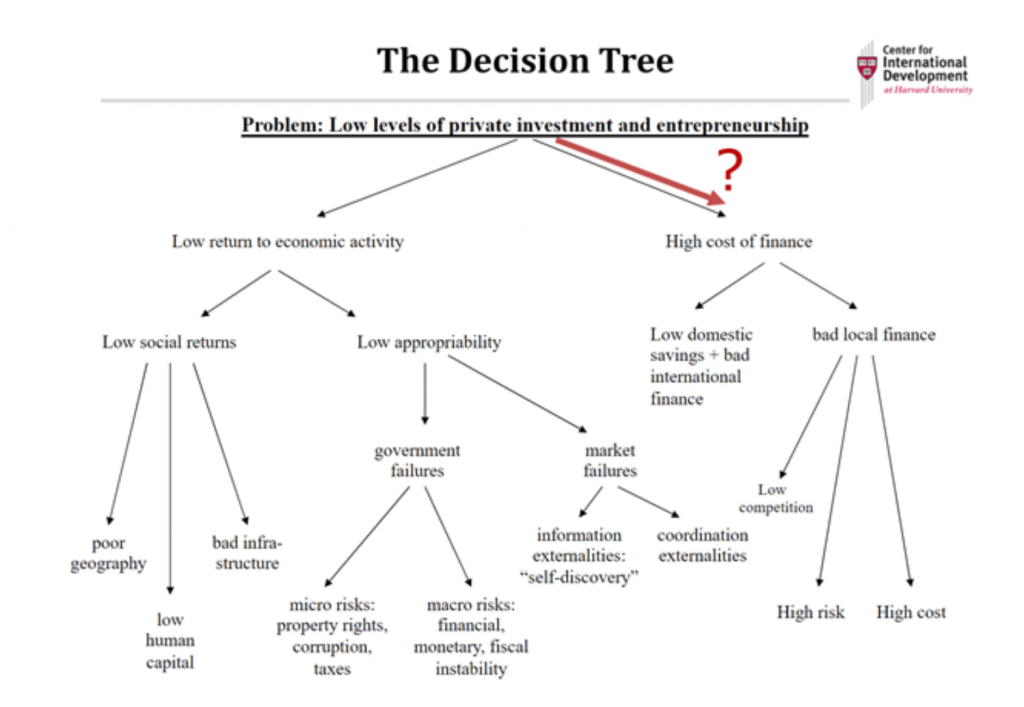

· Finally, you need discipline and rigor to properly identify your growth syndrome and that starts with a differential diagnosis remarkably similar to the diagnosis used in medicine. And just like in medicine your relationship with your patient (industries and businesses) is critical for a proper assessment.

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity and Functional structures of US state governments (Kosack, 2018)

This course also advanced my understanding of economic development by exposing me to growth problems that impacted and still impact other regions of the world. As I mentioned above, the development story in the US is unique. However, learning about international challenges (and solutions) helped me to understand that eliminating binding constraints is the most effective development action that someone can take. As many regions of the world don’t have resources to spare, they need to be very specific about the levers they will use to grow their economies.

HKS’s Leading Economic Growth does not provide you with a silver bullet or answers for all your challenges. Instead you will have at your hands several frameworks and models to better understand and address your region growth constraints.

Source: Course Material – Hausmann LEG 2021 – Wk6S1 – Growth Diagnostics in Practice

We know that investments in infrastructure are capital intensive and the current repertoire of tools used by economic developers are not changing the situation in the regions of the USA that need economic growth the most. So, maybe we should look beyond our borders, and learn how Singapore increased its GDP 10-fold since the 1990’s? Or examine how to do economic development when you don’t have funds to create incentives? And what can we learn from the interesting fact that, Germany and Canada have fewer regional disparities than the United States, but the United Kingdom has the same disparities as the US?

I was impressed with the amount of applicable knowledge and on-the-job training that the LEG course provided. As a former experiential educator, I can say that is no small feat. In a true Harvard spirit, the course discussions and assignments provided me more than the course content.

“The great difficulty of education is to get experience out of ideas.” George Santayana

Source: Course Weekly Assignment – LEG 2021

Lucky me round two. During all this journey including the “special” projects time, I had the chance to test some of these ideas with local legislators, elected officials and agency leads. One specific Representative from my region started asking really good questions and we worked together to see how we could apply some of this to our state and in the United States.

I still have lots of questions on my mind, and, as I review my course resources and notes, I feel well equipped to move forward. However, it would be great to continue to engage with Harvard’s CID and other proponents of this approach to discuss how to improve our national economic development practices.

Source: Metroverse – LEG 2021 exercise with Denver Metropolitan area

Here are a few ideas I would like to explore: How to improve the creation of the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) required by the Economic Development Administration (EDA)? How to turn Targeted Industry Studies (a new trend around the US) into a more precise tool to attract foreign (and in some cases domestic) direct investments? How to involve other practitioners in this conversation and bring analytical innovation to economic development around the USA?

Are you up to the task? Let me know!

Thanks to the diverse and fantastic participants of the LEG 2021. It was possible to learn from experiences in economic development from South Africa, Venezuela, Mongolia, Mexico, United Kingdom, Afghanistan, Brazil and both Wyoming and Oregon, USA.

Many thanks to the Harvard Kennedy School, Growth Lab, and Building State Capability teams for putting together such an amazing learning experience. Special thanks to Eric Protzer for all the awesome things he brings to this space.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Leading Economic Growth Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. 61 Participants successfully completed this 10-week online course in December 2021. These are their learning journey stories.