Guest blog by Ana Maria Chirinos Leanez

After almost two years since the COVID19 pandemic started, policymakers and governments continue struggling with questions on how to deal with concerns on economic growth challenges and how to promote countries’ recovery more sustainably and inclusively. Those topics are very well discussed by the Leading Economic Growth program developed by the Harvard Kennedy School in collaboration with the Center for International Development (CID). It is a ten-week executive program that provides tools for the diagnosis and decision-making related to growth and development for practitioners worldwide.

As a Venezuelan macroeconomist who has been analyzing her country’s complex and severe macroeconomic crisis from a macro-financial perspective, the inclusion of economic growth elements would complete the whole picture of the analysis. For ten weeks, I was deeply immersed in the concepts of economic complexity, Knowhow, product space, growth diagnosis, strategies to promote economic diversification, and how to work with very complex problems using the problem-driven iterative adaptation (PDIA) approach. So, all the discussions were very profound and useful in designing development policies, and selecting some takeaways is not easy. However, I could summarize the most relevant lessons of the program as follows:

• Growth and inequality are understood and analyzed simultaneously. The attention must be focused on economic growth through inclusion and not economic growth for inclusion. In the same way, growth diagnostics, economic complexity analysis provides significant insights on how to comprehend inequality. The economic complexity index is a significant negative predictor of inequality (Hartmann et al., 2017). While growth diagnosis helps find the roots of why our economic growth is not more inclusive. 1

- Understanding the power of Knowhow. An essential part of technology is the ability to perform a task. This is tacit knowledge that cannot be acquired or stored in books, and it is not transferable easily. The technology diffusion is significantly tightened to a level of Knowhow. Even when building knowhow is potentially possible, it demands a lot of time. And knowledge moves when people move. So, it is much easier for countries to attract FDI, diaspora, or acquire foreign firms to get Knowhow than build this tacit knowledge from scratch.

- The PDIA methodology: When policymakers need to make decisions under complex situations, the PDIA is most appropriate technique. It aims to identify the roots of the growth problems (through the five whys or the fishbone diagram) and adapt the analysis to country-specific conditions. Under very complex scenarios, in which we don’t have authority, acceptance, or ability, we need to build or rebuild them. In that case, small steps matter. Doing nothing is not a choice.

But how can these concepts be applied to countries facing very complex scenarios? A good example of a complex economic scenario is Venezuela. During 2013-2020 the economy has shrunk around 76,7%, causing profound scars in terms of economic development. This enormous economic contraction has resulted from the collapse of oil production, hyperinflation, and sovereign default debt since 2017, among other factors. In addition, the impact of the COVID19 pandemic worsened and deepened the pre-existing conditions. As a result, the economy shrank around 30% in 2020 (ECLAC2 and IMF3). Indeed, around 6.3 million Venezuelan have left the country (R4V, Nov 2021), in one of the largest displacements in the world. For 2021, the economy will contract significantly less to the previous period (during 2020 was the largest contraction in the recent history of the economy), between 4- 5 %. However, the economy will still be unable to grow.

1. Venezuela and its inability to grow.

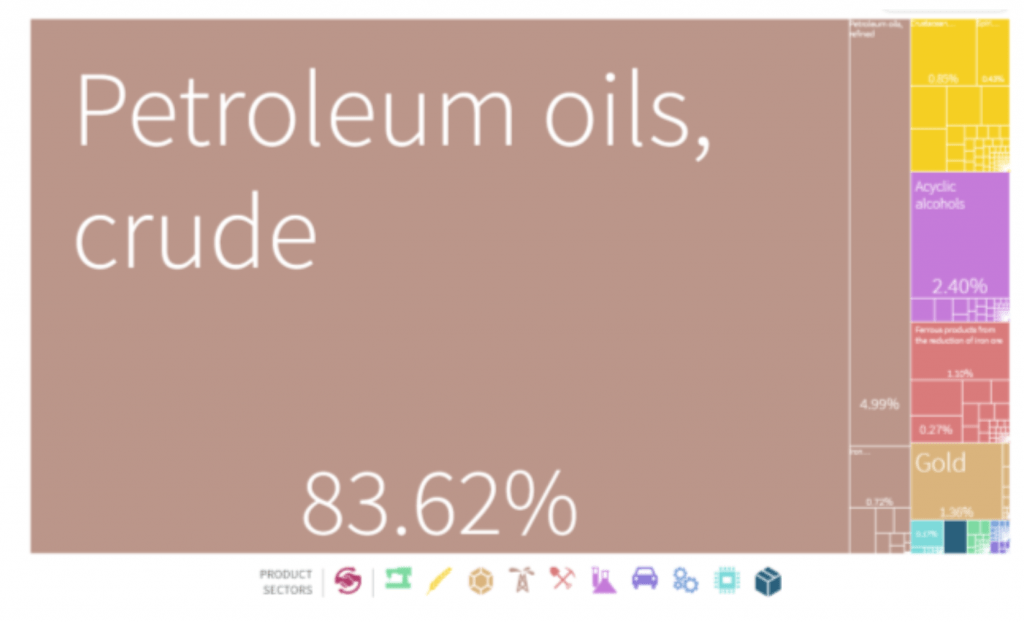

According to the Atlas of Economic Complexity, 83,62% of Venezuelan exports basket composition is petroleum oil, not surprising. Venezuela is mainly an oil economy, with a significant dependence on oil exports (the main source of income) with almost nonexistent diversification. Exports composition has stagnated during decades, and the country has only added two new products since 2004, that contributed $0 in income per capita in 2019. Venezuelan exports are concentrated on a low complex product (a low knowledge-intensive product), and its levels of economic complexity are also low.

Source: Exports basket (2019), Atlas, CID. Harvard

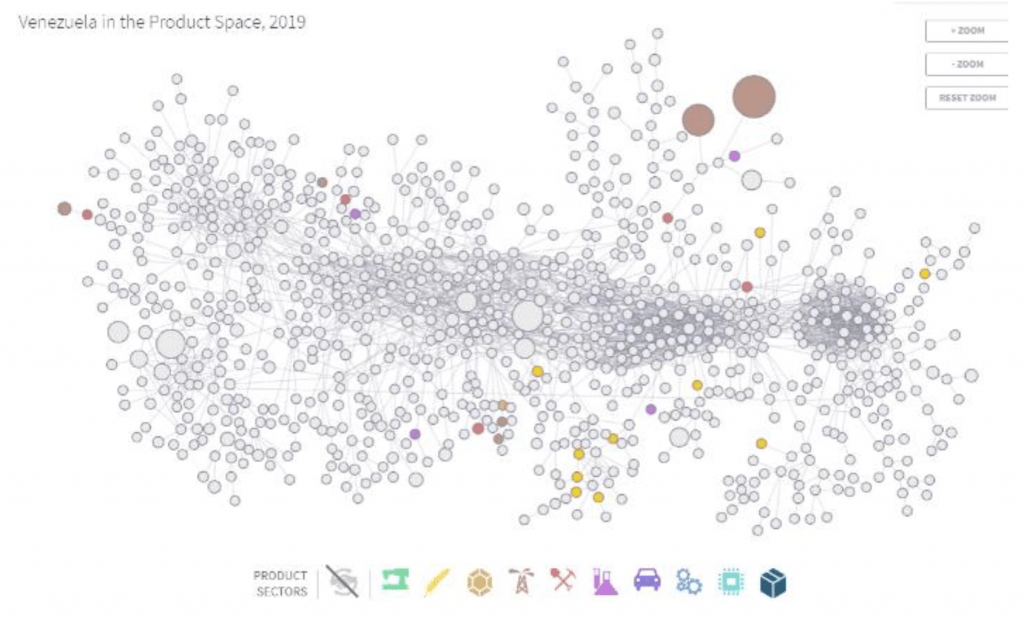

Source: Venezuelan product space (2019), Atlas,CID, Harvard.

Additionally, Venezuela’s high dependence on oil production places the country at the periphery and largely disconnected in the product space, which impedes the discovery of new capabilities. The country has limited space to improve quality and restricted empty activities to enter. The severe oil specialization has been significantly costly in allowing an organic diversification of the economy. Countries are more successful in diversifying when they move into production that requires similar Knowhow. But oil sector knowhow is very limited, oil production requires the extraction from the geological reserve but not much more, and few activities require this specific tacit knowledge. Additionally, even when the country has the largest reserve of oil globally, it is very unclear whether the oil sector will contribute to the economic recovery during the upcoming years. The current conditions of oil production and the end of the era of fossil fuels are substantial constraints.

To recover from an output contraction of 76,7 % (2013-2020) and revert its inability to grow, what are the opportunities to revert the contraction? Furthermore, what are the opportunities for product diversification in Venezuela to respond to the economic collapse?.

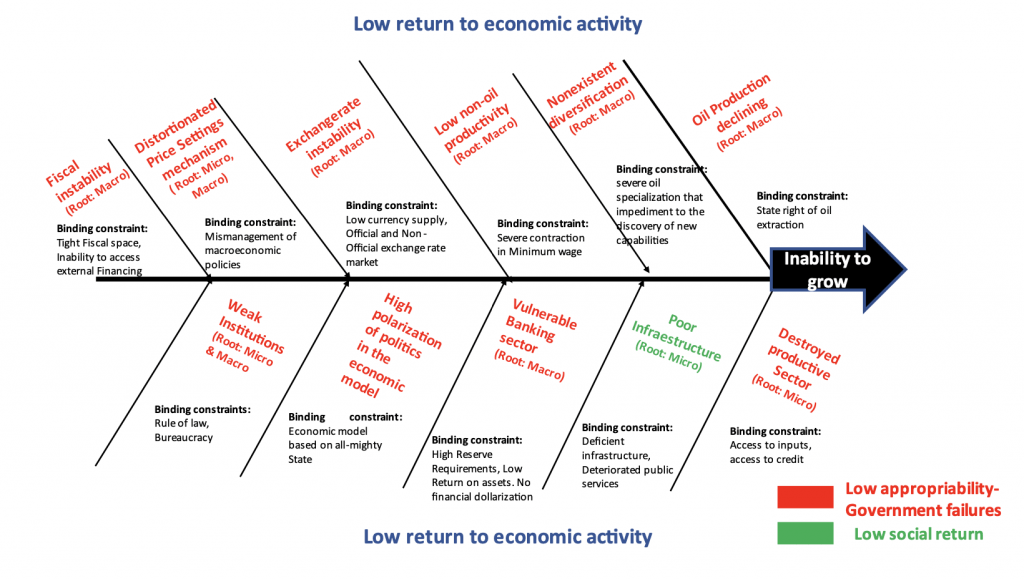

2. Some causes of the growth problem and the fishbone

Applying some of the principles of growth diagnosis (i.e asks questions to rule out explanations of the problem and identifies the main binding constraint of the problem), Venezuela seems to be a very particular case. Simultaneous bindings constraints cause its growth challenge. The complexity of the crisis and the simultaneous distortions among markets could explain the coexistence of multiple binding constraints. This is far away from a unicausal analysis. However, they can be classified as macro and microeconomic causes and binding constraints.

A potential fishbone that could include these aggregate causes and their binding constraints could be:

The most relevant macroeconomic causes include:

- Oil production declining: The government can only carry oil extraction. The oil state company can’t efficiently extract the oil at the current conditions (due to nonexistent investment), and neither can the private sector. Moreover, PDIA actions in this sector seem extremely limited since they are subject to authorization and acceptance from political decisions.

- Nonexistent diversification: High dependence on oil production represents an impediment to discovering new capabilities. This severe oil specialization has been significantly costly in allowing organic diversification. Economic diversification required to increase the economic complexity will be subject to available knowledge and skills. However, massive migration and political and economic conditions don’t attract foreign direct investment, either diaspora. So, where the Knowhow will come? What can Venezuela do to identify its capabilities? After the crisis, what is the remaining set of Knowhow in the country? One can identify those useful capabilities that remain in the country through a household and firm-level survey. The problem in this area would be solved when we can identify the firm’s survival in the country and the capabilities demanded by those industries. But also, the Knowhow that was useful by households in the country before the crisis and prevails in the country. The new relationships will come from the link between the capability and industrial sector, a sort of supply/demand-side analysis.

1 Growth diagnosis and PDIA approach are constructed on a problem-driven basis.

2 Dinámica laboral y políticas de empleo para una recuperación sostenible e inclusiva más allá de la crisis del COVID-19, CEPAL, agosto 2021.

3 World Economic Outlook (WEO), October 2021.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Leading Economic Growth Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. 61 Participants successfully completed this 10-week online course in December 2021. These are their learning journey stories.