written by Matt Andrews

I wrote a blog post earlier this week asking if an African country has what it takes to win soccer’s World Cup. Some people asked why I chose that topic—and especially why I took the time to write this longer paper about it!

The reason is simple. I work on public policy, mostly in developing countries, where many governments try to improve their peoples’ well-being by helping their economies compete better in the world, especially for things like talent, capital, and market access (for exports). These governments are trying to develop the capabilities to compete and I am constantly asking what those capabilities are.

Soccer gives us a window into identifying the capabilities needed to compete. Like economic policy, sport has a public good feel to it, brings nations into regular competition, and is the subject of many officials’ promises to win. So, I wondered if a view on how well African countries have been competing in soccer could help shed light on the capabilities needed to compete (in any international competition).

As a result, I looked at how African countries compete over recent decades, and came away with a negative first view, shared earlier this week, that Africa’s top competitors are actually in the middle of the world’s contenders—who do not compete enough to really challenge for world titles. One twitter comment on this post asked me to “shut up” with this view, and the suggestion that countries like Nigeria lack something needed to compete. They pointed to individual matches in the past where Africa’s top teams have nearly prevailed against the world’s best, often explaining the losses on foul play or just bad luck, and opined that African teams would win and I should quit arguing otherwise.

Let me explain how I understand and assess a country’s capabilities to compete, and where I see the gaps for countries like Nigeria, who I agree are full of talent and can beat any nation on earth now-and-again. (Just watch Kelechi Iheanacho’s wonderful goal against Egypt to see what these players are capable of).

Let me start by noting that countries do not become world contenders by ‘competing’ in a few discrete moments in time, where they appear at a tournament and win one or two amazing matches (as I can still remember watching Cameroon against Argentina in the 1990 World Cup Tournament and as I remember watching Senegal in World Cup 2002 against France, as examples of amazing African achievements).

Rather, countries build their capabilities to compete with the best over time, so that they are ready to produce results in those big discrete moments again and again (with a World Cup win requiring at least four such wins against global elites in a seven-game stretch over just over a month, not one or two big results). As such, I look at how countries perform over decades, and decade-by-decade, not at specific points in time (which others might do and which I think our memories constantly bring us to do, remembering the moment rather than the pattern around that moment).

I examine countries’ records of ‘competing’ over time by looking at two types of performance. I ask how well they ‘compete as participant’, which relates to their record of gaining and retaining access to contests and competitions (where a strong record involves participating regularly in contests against high-quality opponents in high-position competitions). I also ask how well they ‘compete as rival’, which relates to their record of winning contests and competitions in which they participate. Both of these types of performance require capabilities—on and off the pitch—to ensure a country gains access to competitive matches, and to prepare a pipeline of players for those matches, and much more.

What I see when analyzing such performance in the soccer domain is that Africa’s best are behind the world’s best—and have fallen further behind over time. In particular, Africa’s most competitive soccer-playing nations ‘compete as participant’ in far fewer high-quality matches against elite teams than other top nations. And when Africa’s teams play high quality nations they ‘compete as rival’ badly, losing more than top teams from Europe and South America.

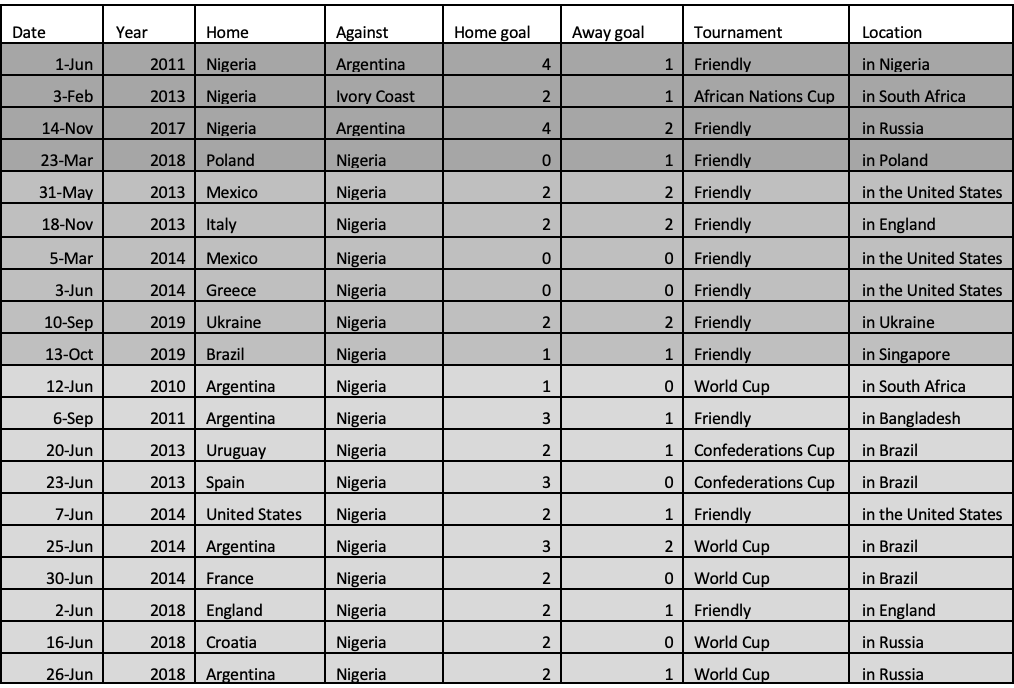

Consider Nigeria, for instance. A dominant force in Africa for so long, the national team played only 20 of its 127 matches in the 2010s against elite global teams (where an elite team in my work is one ranked in the top 10% of teams at the time). This means its record of ‘competing as participant’ in high-quality games (at 16% of its matches) was less than half that of that in England (at 41 %), France (43 %), Spain (42%), and Brazil and Germany (both over 50 %). The Nigerian record is also lower than countries like Belgium and Croatia (both around 28%) and even Greece (19%). Beyond this, Nigeria’s record of ‘competing as rival’ against such teams in the 2010s is poor. As the table below shows, Nigeria has won some matches against these elites (and those are the ones most people remember, against Argentina in 2011 and 2017 friendlies, and against a very strong Ivory Coast team in 2013, and against Poland in 2018). But Nigeria’s overall record against elite teams is 4 wins, 6 draws and 10 losses in the 2010s (based on data from the Elo database, used to rank national teams). This suggests Nigeria will win one out of five such matches, and lose one out of two. Belgium and Croatia have higher win rates (at about 33%, or one out of 3) while countries like England, Spain, Germany, France, and Brazil win close to or more than 50% of the time against elites (such that we can expect they will win about one out of two matches they play over time).

I could present similar data for all of Africa’s top soccer playing nations. The data suggests that these countries lack the capabilities needed to gain and retain access to the world’s top competition and to win when playing such competition.

Note that I am not saying Africa’s national teams lack great players, or play bad soccer, or are failing to make their people proud, and I am not saying that Africa’s teams and others that do not win World Cups ‘suck’ (as one twitter comment suggested I was doing). There is a strong case to be made that national teams always have great talent and play great soccer—and that teams representing their countries should be proud of their representation regardless of whether they win or lose. As the Olympic Creed says, a key part of competing is ‘taking part’. And Africa’s top teams are amazingly talented and have given fans many wonderful memories (including me).

But, these countries say they want to become global competitors, and their records suggest they are not there yet. Why can’t this message be presented without people getting upset? Why can’t it be offered as a thoughtful message that suggests there is more work to be done?

It is a good question to ask what work would that be? One I have—drawing on the gaps I see and other experience–is for Africa’s elite to start ‘playing up’ more than they have been doing—organizing more matches with elite countries more often and in so doing building their capabilities to ‘compete as participant’ and learn to ‘compete as rival’ at this level. I will describe this strategy—and how it was used in other countries—in forthcoming posts but for now let me leave this thought here:

‘Competing’ at the highest level requires participating at that highest level and being able to win regularly at that level. Africa’s elite soccer playing countries are not there yet. But they could be.’