written by Matt Andrews

The Africa Cup of Nations soccer tournament began in Cameroon this week. It has already provided the excitement fans were hoping for. While watching, I wonder how African countries will perform in the World Cup tournament at the end of the year. Is this the tournament where an African team wins, validating those who have predicted such victory for decades?

Predictions of an African world cup win are like the vision statements governments across Africa pen that see their low-income economies becoming competitive high-income ones by 2030, or 2040 in some instances. Such vision statements and predictions engender hope. But is this hope warranted? Is there really a chance that these amazing things will happen?

My new working paper tackles this question using African soccer as an example. I posit that African countries will only win the World Cup if they can compete with the world’s best countries (Hence the title, ‘Can Africa Compete in World Soccer?’). This requires that they compete as both ‘participants’ and ‘rivals’ in the world context, gaining and retaining access to the most consequential contests and competitions and winning regularly in these engagements.

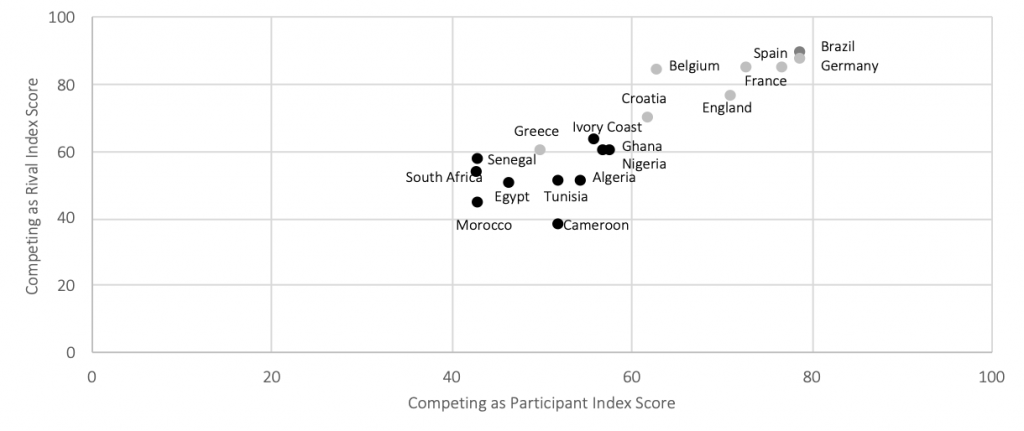

I analyze how a set of Africa’s top contenders have performed as both participants and rivals in every decade since the 1970s, comparing such with the performance of various high-position countries (Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, England, France, and Germany). The results are not promising: A large gap exists between the African and global elite, in the way they compete as participants and rivals, and this gap has grown over time.

The figure below visually illustrates the gap for the most recent decade (the 2010s). You will see that the top African countries bunch together in the center of the chart—where ‘compete as participant’ scores range between 43-58 and ‘compete as rival’ scores range between 38-63 (all out of 100). This block is totally separated from the block elite countries up and to the right, who recorded participant scores between 62-79 and rival scores between 76-90.

Therefore, Africa’s elite soccer playing countries compete ‘in the middle’ of the world soccer-playing community, at about the level of Greece (which is added for reference as it is not a global elite) and well below the levels of Brazil and Germany, France, Spain, Belgium, Croatia, or England. As I write,

“Unfortunately, countries in this global ‘middle’ are unlikely to win the World Cup, which means that Africa’s top competitors do not yet compete well enough to realize their continent’s hopes of winning the world title.

This is not to say that an African country will not beat a global competitor now and again—Ghana beat competitive Czech Republic and United States teams in the 2006 World Cup tournament and won against Serbia and the United States at the 2010 World Cup event.

The evidence does, however, infer that African teams are highly unlikely to beat top teams repeatedly, which is what a country requires to contend with the world’s best—Ghana lost to Italy and Brazil in 2006, for instance, and to Germany and Uruguay in 2010, which limited its progress in both tournaments to the second round and quarterfinals.

The reality is that a country like Ghana, competing as a 60 rival at a 57 participant level, cannot expect to regularly carry the day against countries competing as 87 or 89 rivals at participant levels of 79 (like Germany and Brazil). Countries like Ghana may thus have lucky days and win occasionally, but nothing more.”

The paper says more than this, and much of the content is more positive and forward-looking.

I will cover this content in forthcoming blog posts but want to leave this simple message for now: Africa’s top soccer playing countries are not currently poised the win the World Cup or to become true world contenders. This is the case even for the country that ultimately wins this year’s Africa Cup of Nations (whoever it may be). This country may become the Champion of Africa, but it will probably struggle to win more than one match against an elite global team, dashing all hopes of an African country becoming world champion.

I wonder if a similar story could be told about the hopes of most African economies becoming the global high-income economic competitors their governments have envisioned? And in respect of both African economics and soccer, I wonder how the hopes of victory can be made more real?