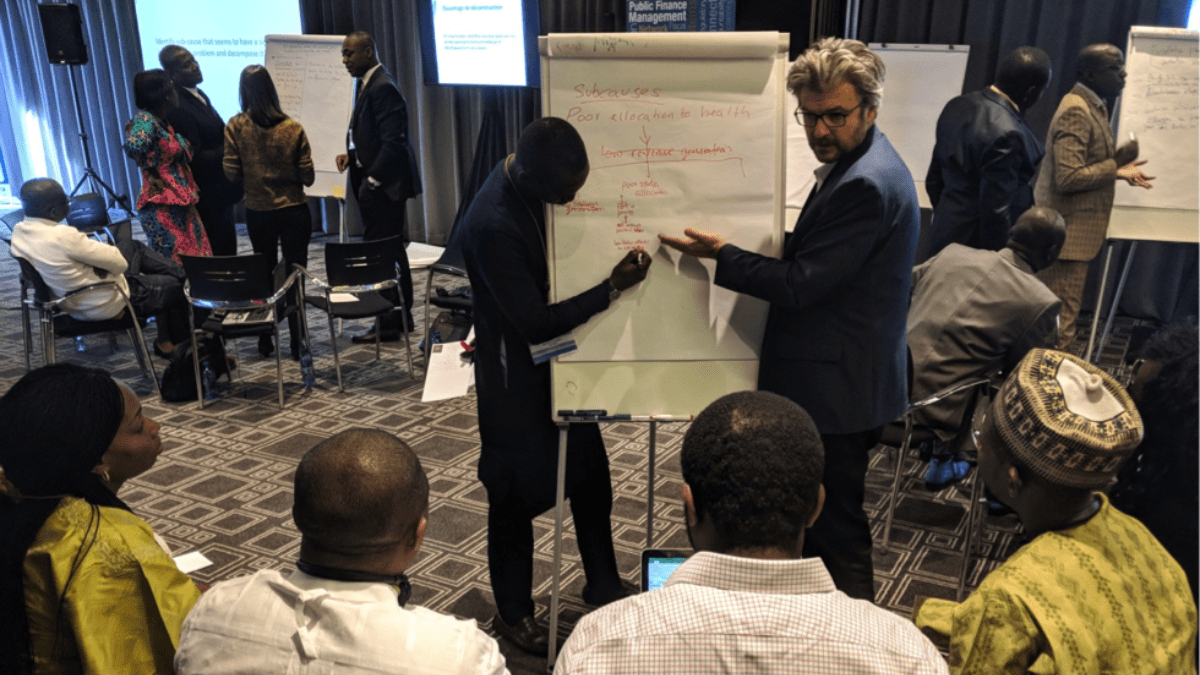

In April 2017, we began our engagement with the Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative (CABRI), an intergovernmental organization based in South Africa, to design and launch the Building Public Financial Management Capabilities (BPFMC) Program using the PDIA approach. In this program, CABRI’s member countries could apply for a team of 5-7 members to work on their locally nominated PFM problem for the period of 7-months. The training included online modules, an in-person framing workshop, virtual progress updates, and an experience sharing workshop at the end of the program. Each team was paired with a coach from CABRI who held regular check-ins to motivate and support them.

Teams from Ghana, Liberia, Lesotho, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa and The Gambia, participated in the inaugural program from May to December 2017. At the end of the program, the teams made significant progress: they developed a deeper understanding of the root causes of their problems; developed capabilities and confidence; financial reporting rates went up; budgets were prepared faster; and virements and arrears decreased.

In April 2018, we began a second iteration, this time offering the program in both English and French. Teams from the Central African Republic (CAR), Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Lesotho, Liberia, and Nigeria, participated in the program. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a funder of the program, commissioned an independent evaluation to assess the application of the PDIA approach in the African context.

The evaluation included desk research, baseline and midline surveys of participants, interviews and observations from the framing workshop and experience sharing workshop, field visits to CAR, Lesotho, and Liberia, and interviews and observations from a review seminar, five months after the conclusion of the coaching support from CABRI.

Our engagement with CABRI ended in December 2018. They continue to use the PDIA approach in their work.

Key Findings

Majority of participants, in the baseline survey, judged that previous PFM reforms undertaken in their countries had been largely unsuccessful and mainly implemented and/or led by external assistance. “When asked about the quality and success of the PFM reforms in their countries, only 33% felt the reforms had more successes than failures and none perceived the reforms to have been highly successful; the other 77% assessed that the reforms had partially or totally failed.”

There is clear evidence that tangible progress has been made towards the resolution of complex PFM problems as a consequence of the PDIA processes as applied by CABRI in CAR, Lesotho and Liberia. “Achieving significant progress towards resolution of complex PFM problems in three out of six countries is an impressive success rate by comparison, especially within such a short time period, the complexity of the problems being addressed and the difficult reform contexts.”

Progress towards resolution of PFM problems has been achieved when three conditions have come together:

- An Authorizer, with genuine concern for the problem and sufficient influence to open up space for the PDIA team to work;

- The Authorizer has devoted focused attention to a relevant problem of local significance, whose key causes and subcauses have been well defined;

- A functional PDIA team, with a specific mandate by the authorizer to search for solutions to the problem and with the capacity to dedicate sufficient time to the task.

In the other three countries (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria), there were shortcomings related to the authorizing environment, the mobilization of capable teams able to dedicate sufficient time on task, and to the problem selection process itself. There were also weaknesses in the diagnosis, and in the adaptation of the problem and related entry points to the realities of the context. However, there was also change which could potentially bear fruit in the future.

The PDIA process, as applied in the 2018 CABRI BPFMC program provided a way for local teams to identify a problem and work through it with stakeholders in a way that develops transferable skills. There is also strong evidence of skills development, right across the cohort, related to problem-solving, team-working, adaptive learning and reform implementation skills.

Follow-up interviews conducted in Liberia in May 2019 (five months after the PDIA cycle had ended) suggest that skills development is likely to be sustainable.

Read the evaluation report.