written by Matt Andrews

Governments across the world are struggling with the many policy challenges wrought by Covid-19. While this pandemic is not yet over, many are already thinking about the recovery to come. Governments will undoubtedly be needed in this recovery process, helping people get back to normal or charting new paths to better normals—what some call ‘building back better’.

I fear that governments are set to fail in their efforts to provide such help, however, because of limits to the budgetary and policy prioritization space needed to address post-Covid needs.

Will we have enough money to build back better?

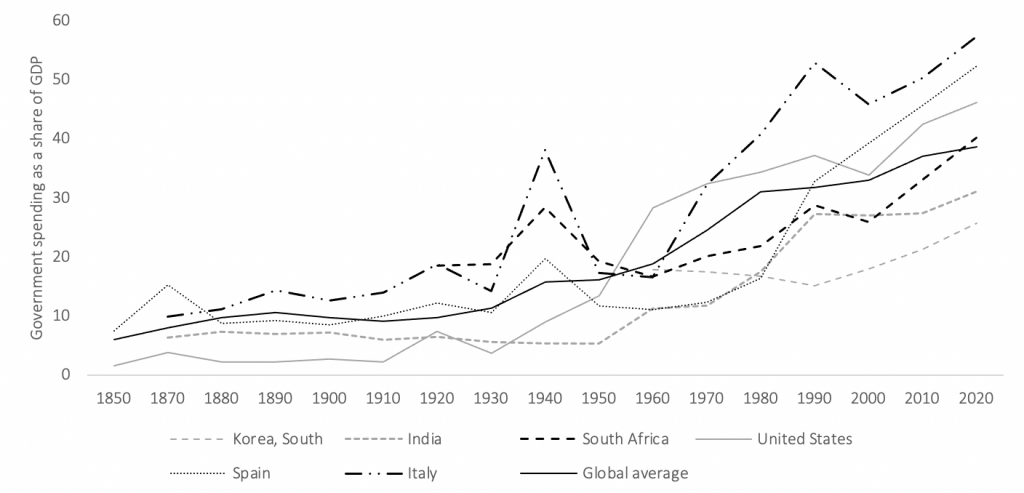

Covid-19 hit the world at a time when many public finance experts were already commenting on the large role governments have turned out playing in their economies. Government spending as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was at historical highs in many countries prior to the pandemic given decades of growth in budgets across the world. Consider the following graph and examples of such growth in countries as varied as South Korea, India, South Africa, the USA, Spain and Italy.

Figure: Government spending as a share of Gross Domestic Product, various countries, 1850-2020

These budgets continued expanding in response to Covid-19, fostering record debt levels across the globe. A Brookings paper written last year notes, for instance, that “In 2020, global government debt increased by 13 percentage points of GDP to a new record of 97 percent of GDP. In advanced economies, it was up by 16 percentage points to 120 percent of GDP and, in EMDEs [emerging markets and developing economies], by 9 percentage points to 63 percent of GDP.”

I hear many public finance professionals reflecting worryingly about such data. Most note—often with relief—that they expect to see the ratios coming down soon. This will happen when economies pick up (and the private sector contribution to GDP grows) and social spending released in the wake of Covid starts to wind down (such that government spends less).

But how will governments find finances to build back better when that happens? Especially when many countries will be paying higher debt financing costs related to their governments’ 2020-21 borrowings. And when the call for more public sector spending seems at odds with the narrative that inflationary pressure weighs heavily on the world economy and should lead governments to be more conservative about spending.

Future budgetary space is needed, however, to help countries recover and to address issues that Covid-19 showed have never been properly attended to. These include challenges associated with the lack of access many people still have to life’s basic things (like a shelter to spend lockdown in, or food while they are in lockdown, or appropriate health care to escape lockdown) and the pressures being placed on our planet (related to climate change, for instance) and the inequalities our past growth patterns have created (of access and opportunity, to safe jobs, vaccines, communications, law and order, and much more).

Are existing budgetary processes up to the task?

Governments will be at least partly responsible for the work needed to address such issues in years to come. Given that the issues have not been properly addressed in the past, however, I cannot imagine the work will be done with the money available in existing budgets. New money will thus be needed, and I worry that it will not be forthcoming. I thus ask pointed questions: Where will the money come from to finance a build back better agenda? And what level of government spending to GDP seems ‘right’ to target as countries plan for the post-Covid world?

Even if we can answer such questions, and money is available to rebuild, I worry more that existing budgetary processes will not ensure the funds reach new (or newly pressing) policy challenges (especially when these policy challenges involve groups who were previously excluded or ignored by policy processes).

My worry stems from the observation that public budgeting processes tend to absorb new finances through ‘layering’ more often than ‘addition’. This means that new spending usually builds incrementally on old spending, such that policies accumulate on top of existing activities instead of adding new ones. This happens because budget allocation processes are political, with spending allocations controlled by incumbent political claimants. These incumbents often even structure technical mechanisms to keep new claimants at bay (with budget processes commonly designed to prioritize incremental growth in existing policy over new proposals, for instance).

Given such observation, I worry that the budgeting processes currently in place in countries across the world will not accommodate new policies through ‘addition’—allocating resources to new claimants to pursue new policy activities and address new policy challenges.

Such worry leads me to ask additional questions: Can existing budgetary processes be re-shaped to include the voices of new claimants needed to inform new spending allocations? What political and technical changes will be needed to make this happen?

These are the kinds of questions I am tussling with right now, as I prepare for the forthcoming Public Finance in a Complex World executive education course (which will be online from January 24 to 28, 2022). This kind of course is needed now more than ever, and I hope some of you might be able to attend and join the conversation about creating space for better post-Covid public policy spending.