Guest blog by Thierno Olory-Togbe

As a Principal Legal Counsel at the African Legal Support Facility, I have the opportunity to advise African governments facing inadequate capacities in strategic sectors such as sovereign debt, infrastructure and natural resources. Despite the increased efforts of African governments in improving public sector efficiency, the optimization of benefits from the exploitation of natural resources and economic diversification remain critical to reduce poverty on the continent.

The current COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant global economic and financial crisis have led to major disruptions for African governments in the achievement of their development objectives. This challenge requires practical problem-solving approaches. Hence, my participation to Harvard Kennedy School’s executive course on “Leading Economic growth” was an opportunity to better understand how this could be done from a very practical perspective. It was an opportunity to learn how to use appropriate diagnosis, decision-making and implementation tools.

I was initially planning to work on “how the Government of Benin can mobilize resources to improve productivity and recover from the COVID-19 crisis”. During the learning process of the course, my growth challenge was slightly reformulated as follows: “How can the Government of Benin improve productivity and lead the recovery from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis?”.

Having myself tested positive and recovered from COVID-19 while staying in Benin, I particularly admired all the efforts that the Government was deploying despite very little means and I wanted to offer solutions to overcome this challenge.

My interest in this topic was also driven by observing the economic gap between Cote d’Ivoire (where I work) and my home country Benin (where I relocated during the pandemic). Both countries are located in West Africa, use the same currency and apply similar legal systems. According to the World Bank, Benin’s GDP per capita fluctuated between 1,036.53 US Dollars in 2010 and 1,219.43 US dollars in 2019, while Cote d’Ivoire GDP per capital constantly grown from 1,213.11 to 2,276.33 over the same period.

In 2020, both economies were affected by the pandemic as the demand for their usual sources of income (agriculture and tourism) dropped, and the global economy shrunk by 4.4% according to the International Monetary Fund.

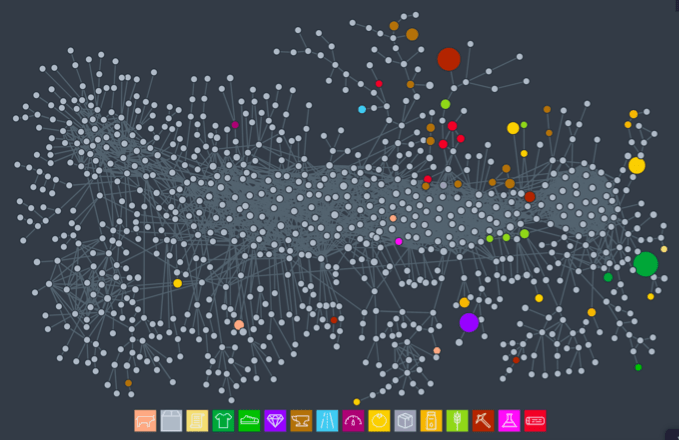

At the beginning of the course, we have had the opportunity to discover and work with the he Atlas of Economic Complexity of Harvard’s Growth Lab which measures the amount of productive knowledge that countries around the world hold and how they can move to accumulate more of it by making more complex products. Benin was not referenced on this atlas but thanks to guidance from the teaching team, I was able to find data on Benin’s economic complexity on the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC)’s website (https://oec.world/en).

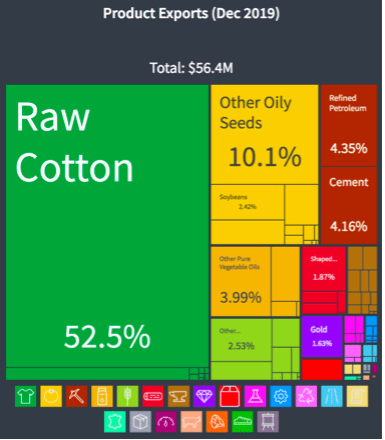

Data shows that Benin’s economy is poorly diversified and not complex enough. Exports are mainly composed of agricultural products, in particular cotton ($467.50 million in 2019, representing over 50% of total exports), followed by cashew nuts, cocoa and maize. The country also imports and re-exports petroleum and manufactured products towards Nigeria (21% of total export destinations).

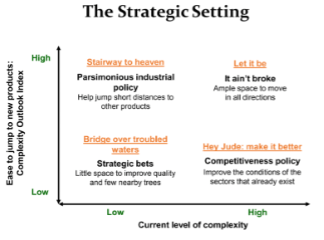

Through the diagram below, Professor Ricardo Hausmann recommends that an economy should seek to improve complexity by importing knowhow and implementing one of the following four approaches: “Bridge over troubled waters” (Strategic bet), “Stairway to heaven” (Parsimonious industrial strategy), “Let it be” (Room to grow up and out), “Hey Jude: Make it Better” (Competitiveness policy).

In the case of Benin, the current level of complexity is low and the current know how in the country makes it difficult to develop new products for exports. Hence, the “Strategic Bet” approach is recommended.

During the pandemic, the reduction of global spending on apparel and other cotton products in connection with shutdowns (particularly in the United States and Europe) led to the decrease of Bangladesh, China and other Asian countries’ clothing production and the demand for raw cotton. It is important that the Government takes action to mitigate the risk related to volatility of cotton market and make bets to explore new production areas.

The course modules provided additional tools to further analyse Benin’s growth challenge. These include the use of the “5 Whys” technique consisting in exploring in an iterative manner the reasons behind the identified challenge, as well as the recommendation to implement “high bandwidth organizations”. The combination of such approaches offers the advantage of focusing on the problem-solving process rather than the solutions themselves (an echo to solving Professor Matt Andrews’ 1804 adventurers faced in getting west without roads). This ensures on-going and practical interactions between officials involved in designing the growth strategy and stakeholders. It encourages organizations and teams to acquire a better understanding of the rationale behind their growth challenge and rapidly take actions from which they can learn new lessons and make adjustments in an iterative manner.

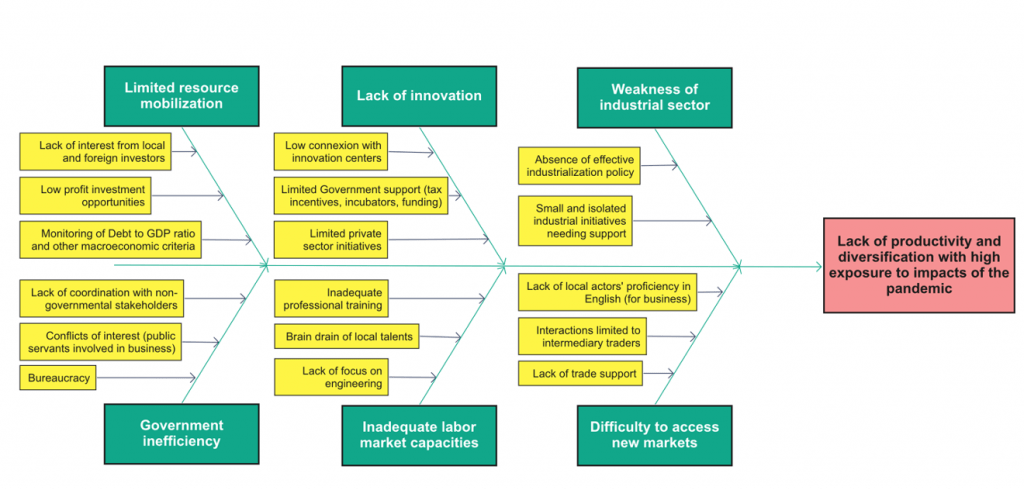

These approaches were complemented by the realization of a “Fishbone diagram” to diagnose the real issues to be tackle and identify smaller steps to address the identified growth challenge. My proposed Fishbone for Benin’s growth challenge is presented below.

The country is largely dependent on foreign aid and investment to increase productivity and develop new industries that could sustainably generate more value than the traditional agricultural goods. The use of the Fishbone allowed to propose small milestones rather than attempting to copy-paste existing “action-plan” solutions. This would allow flexibility and on-going adjustments. Proposed entry points include: resource mobilization and improvement of Government’s efficiency in managing those resources. Indeed, these binding constraints have particularly received endorsement from various stakeholders since Benin is classified as a “non-resource intensive” and “low income” country. Governmental coordination is also proposed as a key entry point.

A few years ago, the Government created the Agency for the Promotion of Investments and Exports (APIEx) which is a coordination structure that serves as an interface between investors and the relevant ministries and government agencies. Benin has also recently established a “Deposits and Consignments Fund” (Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations du Bénin – CDC Bénin) which may be further operationalize in order to mobilize national resources.

Beyond external resources, Benin may mobilize national resources locally by securing the collection of taxes through the dematerialization actions, organizing the informal economy, and establishing innovative instruments for collection of national savings. Other ideas derived from the modules also include the strengthening of governmental coordination, the conduct of awareness actions to ensure a wide dissemination and endorsement of reforms, as well as an increased engagement with neighbour country Nigeria, Africa’s leading economy.

Improving Benin’s ‘sense of us’ would also be critical to achieve citizens’ engagement towards more productivity and commitment in the recovery from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis. Before being able to integrate itself better in the global economy, the country must ensure that the gaps between the north and the south of the country are filled. A better distribution of wealth across the regions should be taken into account in the definition the country’s strategy.

Throughout the course and assignments, I have understood that the productive transformation of Benin shall begin with the creation of opportunities that allow the development of existing skills/advantages and the accumulation of diverse know how. Economic growth in Benin may not require huge innovations, but rather the development of local capacities and the import of competencies, especially by offering back-up industrial facilities and workforce to Nigeria or other countries. It may also be envisaged to visit other model countries which have succeeded in growing as as a nation and diversifying from agriculture to new areas of production. These opportunities in turn require coordination efforts from the public sector.

While taking this executive course on “Leading Economic growth”, I have had the opportunity to discuss with officials at APIEx and CDC Bénin. I shall continue engaging with them and share some idea in order make a positive impact on the development of my country.

Last but not least, despite the distance and the online format, this learning experience was a unique opportunity to engage with a variety of professionals from all over the world, especially my teammates in Group 12 (“Change Disruptors”), the course Professors and Teaching Assistants, and the entire LEG 2021 Cohort.

Thank you for this great opportunity.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Leading Economic Growth Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. 65 Participants successfully completed this 10-week online course in May 2021. These are their learning journey stories.

To learn more about Leading Economic Growth (LEG) watch the faculty video, and visit the course website.