Guest blog by Gabriel Aduda

My initial attempt at being part of the very first edition of the Implementing Public Policy Program in 2019 was fraught with challenges, due to my work schedule. At that time, I was responsible for organizing national events in the Presidency, Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation and also saddled with organizing the Transition to second term of the Buhari Administration and the Democracy Day 2019 on 12th of June; an activity that was significant, as it was just a few days away from the second term swearing in of Mr. President. The thought of me heading to Boston to attend the physical kickstart of the program at the same period was clearly unthinkable and my boss simply said to me without looking up at me across his table “.I am sure you have deferred your course at Harvard” to which I replied without arguing “on it sir” and I went off to drop Amber a mail…. the rest is history.

I resumed the IPP2020 online course with a huge expectation going by so much we had heard of Harvard Kennedy School. I was excited about the diversity of student make up from about 40 countries and was looking forward to interacting and learning from others, however nothing prepared me for the rigor of the course and the experience that was ahead of me.

The elucidation that came from the sessions on planning, and control left me wondering why developing countries continue to engage the plan and control model of planning day in and day out, despite knowing it is most often than not doomed to failure. Why do we continue to hinge our policy implementation and budgeting on same? Indeed, for some of us that look critically at the system from within the service, we most times tell ourselves these policy makers are unfair to the system, thinking they are not interested in following through with policy implementation or they would have seen failure written all over their proposals in the name of implementing best practices. The case often, is a well thought out and written policy that meets best practice standards, but implementation often is the challenge of aligning policy products such that they make actual impact in the targeted sectors.

Delving deeper into the course, newer questions began to emerge, especially as it relates to a new dimension to policy implementation and the Policy Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA). This incremental Mode of planning quickly set me to interrogate the combined role of civil servants and politicians in pursuing seemingly unworkable models of policy implementation, and how each group is culpable, though the blame is often alluded to politicians. Case in point is the normative process of politicians in designing budgets based on plan and control, which is often accepted and implemented by civil servants without PDIA. Since these sessions, I have learnt about the holistic engagement and inclusion of PDIA in the process of implementation. Drawn from this, I understand that by engaging the various elements of the process and by unravelling the problem in small bits, one is able to learn, adapt, implement and as many times as necessary, repeat the process. The consequence of this process will be evident in our small wins, build on them while making progress. The PDIA is a hands-on approach that helps build capacity to address challenges while already working on and solving the problem.

Defining leadership as disappointing your own people at a rate they can absorb couldn’t have been timelier for me, as my key policy and mentorship challenge has been to motivate people to move away from the norm, the status quo, what they are used to doing into new and uncharted waters; this has bred some level of resistance. While change is often complicated, and doesn’t always happen the way you envision, it is my duty to effectively manage and communicate their perceived losses and show my stakeholders that the gains in the long run will be more beneficial to them and the system. This is a factor in my policy challenge as my team and I, in the bid to support the Federal Governments goal of diversification are transforming sporting activities from recreation to business by creating the enabling environment for private sector engagement and achieving less dependency on government funding. This includes a stakeholder mapping and analysis, and a communication, rebranding and marketing strategy that sets the tone for our shared vision of the future of sports, such that the relevant stakeholders see in clear terms the picture of the proposed end results. Policy planning and implementation is all about human capacities and the degree to which they are productively engaged determines the rate of success. This has helped me to see things differently because while the policy deliverables were the ultimate results that I would ordinarily focus on, effective leadership on the other hand draws on the importance of working with people, creating teams and interrelationships in the process, from conception through planning, implementation and ultimately, to sharing end results. While there has been no dearth in ideas as to where we are headed as a ministry and what we think needs to be done to achieve our goals, we now have to deal with the private and social sectors, we are seeing new perspectives being brought to the table, some of these we never even saw coming (thanks to iteration). For example, some private sector players who are also very crucial stakeholders, feel that sporting activities should be removed completely from government purview and be allowed to run independent of government rules and regulations. Balancing these expectations with the requisite regulations that government institutions provide all form part of these changing dynamics in the sport management sector and in need of policy attention.

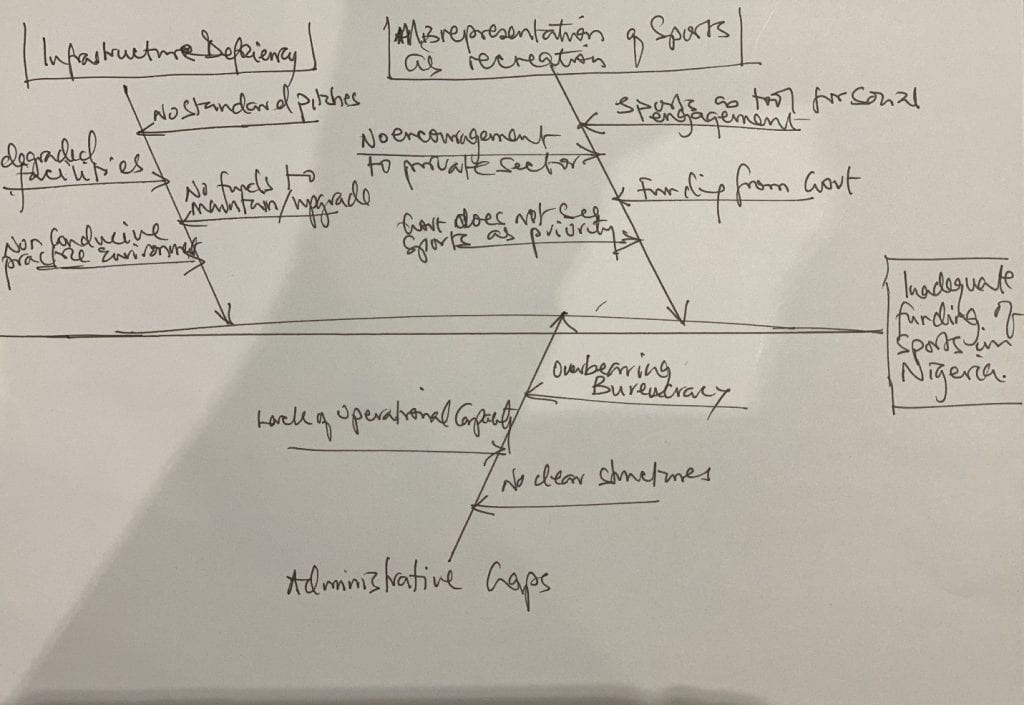

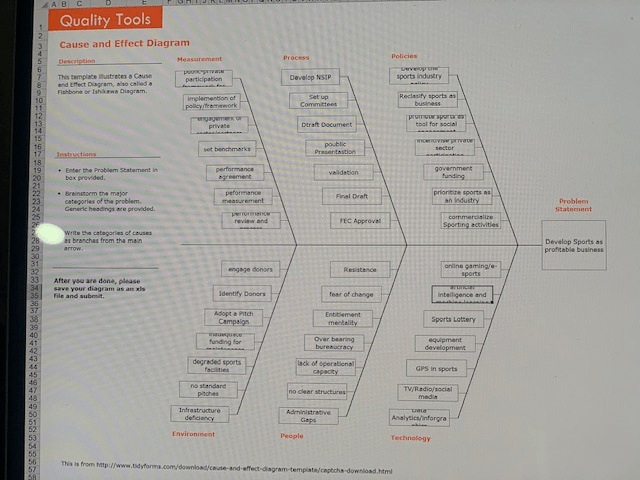

The Fish Bone concept further brought to the fore the complexities and connectedness of issues inherent in my policy challenge. As I took a deeper dive into sources of problems and tried to segregate and isolate issues while paying attention to dependencies, this made me realize many more problems that could not be isolated and needed to be addressed in our pursuit of an all-inclusive sports industry policy. The difference between my initial fishbone diagram and what I ended up with as we made progress in the course clearly shows the superiority of the PDIA model of policy implementation which requires that we Pay attention to the problem! Dig, Dig and Dig until you get to the root of the problem, it is only then that you begin to be truly effective in addressing policy challenges.

Ability to link causes and effects in identifying and solving problems now provides me with a model that allows for measurement and appreciation of progress in small bites. This also when well communicated helps to carry along my authorizers and team members alike.

The IPP 2020 I would say has been most impactful and has delivered much more than I expected. I can say I am a better leader today because I dared to undertake this action learning course that put me on my toes, hence activating my practical learning capacities. It has improved my drive for critical interrogatories, as there seem to always be more than meets the eye. With the fishbone concept I can dig deeper into issues and structures to unravel and deal with root causes and their subsequent effects. PDIA has taught me that every seeming end is a beginning in itself, if only I can pay attention to the lessons with a view to understanding, learning from and adapting to requisite changes and options in the journey of policy implementation. My temperament, disposition and people skills also play a huge part in how my team members, authorizers and subordinates relate with me and I relate with them which ultimately impacts my result. My ability to celebrate and project small wins is a huge motivation to teamwork and assurance to my authorizers that we are on the right track, these must never be swept under the carpet or allowed to go unacknowledged.

Finally, studying along with many others, listening to and in some cases contributing to their challenges was like travelling around the world without leaving the confines of my workspace. It is an experience I will hold dear for a long time.

There is always another opinion and we must be open to listening to others with the intent to learn and adapt where necessary.

This is a blog series written by the alumni of the Implementing Public Policy Executive Education Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. Participants successfully completed this 6-month online learning course in December 2020. These are their learning journey stories.

Learn more about the Implementing Public Policy (IPP) Community of Practice and visit the course website to apply.