Guest blog written by Mer Carattini, Sasha Mathew, Imara Salas, Kishan Shah, Katie Wesdyk

The PDIA process taught us how to turn a ‘wicked problem’—a highly complex tangle of many problems with high uncertainty—into manageable components that we can begin to address. We learned a strategy for how to deconstruct an abstract problem with the fishbone framework. Most importantly, we learned that complex problems in unfamiliar contexts can be addressed through a structured approach. We had the chance to put theory into practice by working on radicalization in France.

There was a lot to unpack for the problem of radicalization in France. We had the opportunity to work with our authorizer, Raphaël, whom currently serves as a cyber security expert to the BNP Paribas Bank and Board members of think tank “Les Jeunes IHEDN.” His initial problem statement was to detect, react to, and prevent radicalization within private companies. However, it is very difficult for private companies to play a constructive role in the radicalization debate because of how sensitive the issue is and because there is a lack of dialogue even at a community level. But before we could start a conversation, we had to zoom out on the big picture to grasp the full complexity of radicalization.

Many of the causes were complex manifestations of economic and social exclusion, clashes between French and minority values, government policies, and exposure to radicalized groups. We looked to positive deviants and external best practices for inspiration in how to address these factors. Our research highlighted the importance of communities, civic education experts, victims of radicalization, and formerly radicalized persons themselves. We saw how seeming simple matters such as logistics for meeting planning (especially during a pandemic) could become roadblocks. When our authorizer decided to transition to establishing a new association, École Marianne, his authority expanded to a more political sphere opening new levers. We saw how the interactions of authority, acceptance, and abilities were intertwined and dynamic—it was our job to find the intersection of all three.

Learning how to build a team, specifically a ‘Team B,’ was perhaps one of our greatest takeaways. We learned how psychological safety and investments in getting to know each other was critical for not only bonding but for growing our shared commitment to the work. We became increasingly nimble, flexible, and determined to make an impact on the problem. The acts of kindness were all memorable – and very important to building bonds in a remote environment. It was incredible how much impact one small act had on our team dynamics.

Additionally, we saw how crucial getting live feedback from the interaction of our ideas and the real world is. The sooner we can introduce practical prototypes and engage with other stakeholders and finally the target users, the faster we can learn and more forward. The roadblock is often in getting through all the challenges in moving from the theoretical to the actual (e.g., authorization, fear of failure, perfectionism, logistics). We were amazed how much could be accomplished when we lean into uncertainty and accept these challenges, rather than attempt to evade unknowns and launch into planning. We were able to take a step back, come together as a team around a common problem, and strategically decide how and where to focus our energy. This approach is certainly something all of us plan to take with us beyond school.

Progress made and insights gained

We made progress around refocusing and re-scoping the full perspective around the problem. When we first started this project, our authorizer wanted to focus on the role that private companies can engage with cyber spaces to combat radicalization. However, when we delved into the root causes of radicalization in France further, we found that this approach may not be as effective. Our research consistently highlighted that an emphasis on surveillance, detection, and punishment fails to solve the circumstances leading to radicalization, serving more as a band-aid to help mitigate the impact of those already radicalized. In some cases, measures focused on punishment have instead increased the lure of radicalization by exacerbating the ostracization of vulnerable populations. While preventing acts of extremism is a very important matter to keep potential targets safe, it will ultimately not mitigate the root causes of extremism. We wanted to do more to address radicalization to prevent it from happening in the first place.

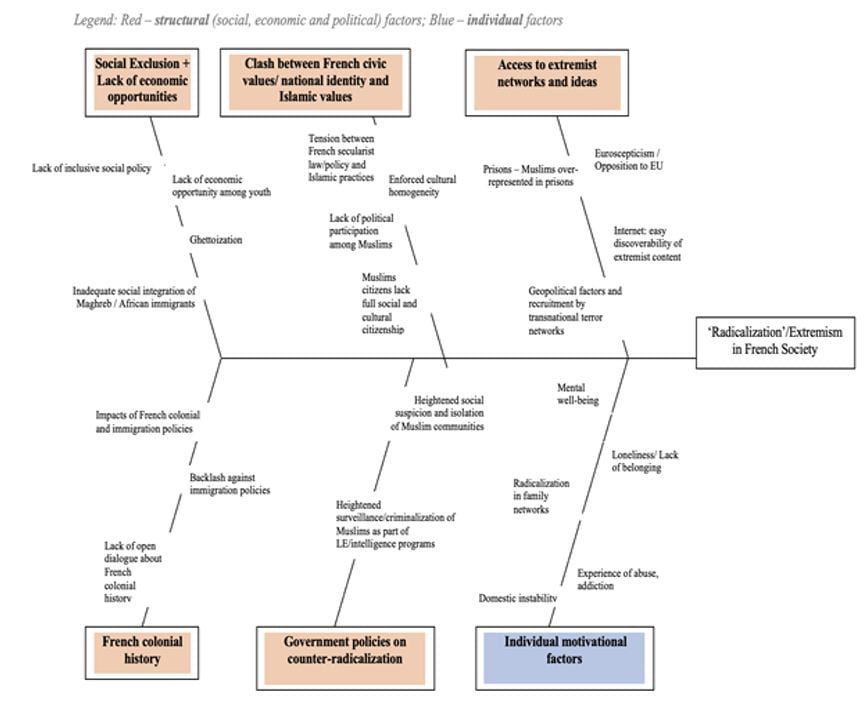

Many of the root causes had less to do with online access to content, and more so with motivators pushing vulnerable populations towards radicalization to begin with. The root causes emphasize structural issues of identity, history, and the ways the current expression of French Republican values come into conflict with the realities of people’s lives everyday. One theme that came up repeatedly was the lack of language and dialogue to even engage through meaningful discussions around these issues. Our first attempt to deconstruct the problem can be seen below in our initial fishbone:

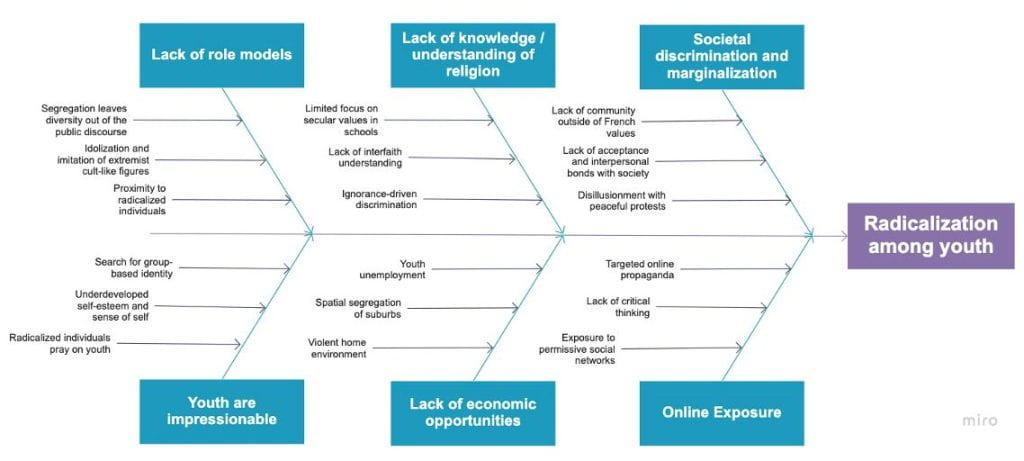

Partly through a shift in focus, and partly also through a serendipitous turn of events, our authorizer also changed his focus from cyber to youth education. At first, this change seemed abrupt, but it also opened up more possibilities to engage with the root causes of radicalization.

As we researched efforts at youth education and engagement further, we found interesting examples of best practice elsewhere and positive deviance in France itself. Abroad, there were already interesting online and offline educational modules for combating misinformation and having greater conversations around diversity. In France, we came across an interesting NGO that was engaging with youth in French minority communities. Rather than taking a punitive approach, their main method was just to talk and listen to youth. We updated our fishbone with this new emphasis on factors that are particularly relevant for vulnerable youth populations:

We took these lessons and models to the broader team, and they informed the design of an action learning agenda to design new online modules for digital literacy and citizenship for French youth. Specific next steps included creating a paper minimum viable product version of the online modules and testing design considerations directly with youth and educators.

Words of wisdom

PDIA is hard and exhaustive work. We came together in a very short period of time to attempt to tackle an immensely large problem that many have struggled to make a dent in. It was an ambitious task with so many unknowns. We realized we had to rely extensively on each other and the unique backgrounds and expertise each of us brought to the table, leveraging the PDIA model as a means to structure our thinking. We had to learn quickly and adopt, requiring time, effort, and commitment from a group of individuals suddenly bonded over a shared dedication to helping our client. We were motivated by the importance of such work where lives are on the line.

Our first advice to other students/practitioners is to maintain open channels of communication with their teammates and other stakeholders. This will help manage expectations, anticipate setbacks, and adjust their line of work on the go. During our work, routine meetings and check-ups allowed us to pivot quickly and respond to problems in a timely manner.

Second, establish a trusting and caring environment. Planning small acts of kindness to each other can go a long way in building team rapport and make brainstorming and ideation much more constructive activities. This strengthens the quality of your work and your ability to adapt and iterate together. It can also help make Zoom a less forbidding environment to work in!

Third, expand your circle of engagement as much as possible. You may never have a ‘complete’ picture, but you can come close by integrating as many perspectives as possible. In our case, having a broad network of collaborators was extremely useful when it came to shifting our line of work and engaging new stakeholders.

Fourth, construct your fishbone as rigorously as possible – and be exhaustive, because this will form the canvas of the change space. Building a comprehensive fishbone will also help you adjust your work based on challenges you encounter and have a systemic outlook of the problem. This will be critical when analyzing the implications of the ideas you propose on other actors of the system.

Fifth, don’t be shy about revisiting the problem. Your understanding of the problem may never be perfect or complete, so be comfortable with revisiting it and expanding on or modifying fishbone diagrams, as you continue to engage stakeholders and deploy iterations.

Always keep the broader perspective of what your goals are and be compassionate towards yourself and team with respect to the constraints you are operating under. As students, it could be overwhelming to try and make headway on a wicked problem in 7 weeks. But the goal of PDIA is not to try and solve all the world’s problems right away. It is about recognizing that too often nothing gets done and something no matter how small is better than nothing. You will be surprised by how far small steps can take you.

We were so appreciative for the opportunity to work together as a team, put PDIA into action, and help with such an important problem. We hope you also find PDIA meaningful to your work!

Watch the video and view the slides of the PDIA in Action event held in June 2021.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2021. These are their learning journey stories.