Guest blog written by Nathalie Gazzaneo, Tendai Mvuvu, Rodrigo Tejada, Matt Weber

On a winter’s afternoon in early February this year, a Mexican MPP1, a Brazilian MPP2, a Zimbabwean MC-MPA and an American MC-MPA randomly stepped up to the plate of abandoned projects in Nigeria. We, the four students and travelers, had never crossed our paths before (more accurately, we had never seen each other over Zoom). Additionally, none of us had ever worked in Nigeria. Before you think it could not get more chaotic, we had only 8 weeks to learn and experiment as much as we could on the assigned problem before coming up with novel and actionable ideas to expand its change space. Ready. Steady. Go! We weren’t ready, the journey wasn’t steady, but we definitely went on.

Maybe one of our first and most powerful realizations in our PDIA journey was that there was no silver bullet fix to the problem of abandoned projects in Nigeria. It took us two entire weeks to look at the problem with more curious and deconstructive eyes until we managed to draft a set of plausible causes and sub-causes that could be at its roots. We had to remain patient and above all curious and collaborative to shift from our initial planners approach to the searchers perspective required by the PDIA process.

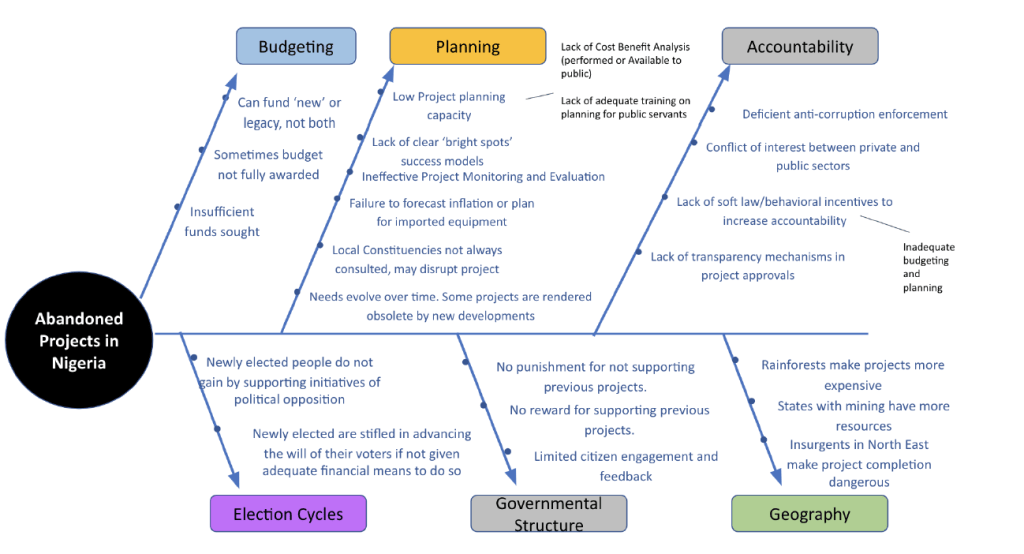

As we deconstructed the problem through interviews and research, the Ishikawa fish diagram and the “five whys” heuristics helped us organize our insights in a meaningful fashion. At this stage, we also started to become more wary of our language usage versus our authorizer’s language usage (more on that later). And as our inquiry and knowledge deepened, so grew our ability to ask smarter questions and to find viable entry points.

An overarching realization throughout the PDIA process was that quick, iterative, practical learning opportunities are more valuable than strategizing the ultimate solution. It can be easy to overestimate our ability to identify causes of a problem and to come up with solutions that look good on paper. Constant iterations of practical steps counter this urge.

Making progress in making sense of the problem

It soon became clear to us that the problem of abandoned projects in Nigeria was not monolithic. Instead it is a chronic and multifarious condition spanning 50 years. Conditions are intimidating, but as we applied the PDIA method, we developed an increasing sense of authority in considering various aspects of the condition, what could feasibly be done by our authorizer and what effects different actions could have.

The condition we confronted specifically was rooted in four main problems to which many of us can relate:

(1) difficulty in continuing projects after government transitions;

(2) inadequate problem-driven planning;

(3) poor budgeting consideration; and

(4) lack of accountability over projects’ rollout and outcomes.

As we iterated on these problems we learned about a pending legislation, the “National Monitoring and Evaluation” policy. This legislation provides an avenue for programs to be reviewed and compared in a way that is more objective and less political than the existing ways in which projects are reviewed as new administrations take office. If this policy could be proactively adopted at the Plateau State level then abandoning or suspending a project would have to be a qualitative judgement based on objective merits rather than on political expediency. This entry point would affect issue 1) described above.

We also came across a civil society based mobile app called “Eyes and Ears” operating in the neighboring Kaduna State which could create an important source of accessible transparency between individual citizens and governmental representatives. This is important because as it stands, neither citizens or officials may know the exact status of each project being built. Adoption of “Eyes and Ears” in Plateau State would address issue 4) listed above.

Finally, we found that the executive branch of the state government didn’t have a way to interface with the legislative branch of the state government which was part of the reason why the legislative branch seemed to make arbitrary funding decisions that departed from submitted project budgets. Bolstering communication between the legislative and the executive branch would improve issue 2) and issue 3) listed above.

Words of wisdom for other PDIA travelers

In navigating the problem of abandoned projects in Nigeria, we learned much more than our fishbone suggests. Beyond budgeting, planning, accountability, election cycles, and institutions, we learned valuable lessons about teaming, intellectual humbleness, and the power of dissecting causes and questioning our assumptions. Here are our key lessons for other students and practitioners traveling in the good company of PDIA.

1. Resist the silly urge to think you are the ultimate problem solver. Do small things to learn about the problem, to feel progress, and to have a reason to ask the next question. Each step builds personal authority and a living network of people to vet new hypotheses with. Each of these small steps taken fosters sensitivity, confidence, and a desire to share learning or test hypotheses within the larger group. The mindset of small steps engenders humility and constructive collaboration..

2. Get in the habit of honestly asking instead of telling. Be explicit when asking about your authorizer’s and stakeholder’s authority, acceptance, and ability. The AAA analysis will change as you obtain more information and become more familiar with the power dynamics of actors that can influence the issue at hand. The aim of PDIA is to achieve actual progress, and that requires being able to assert challenging ideas. To do that in an inclusive manner through questions rather than proclamations means that group members, stakeholders, and authorizers have the highest probability of buying into your ideas and considering them fully.

3. Teaming is an intellectual science as much as an emotional art. Performing acts of kindness conscientiously creates an esprit de corps that created goodwill that was crucial to a highly functioning team. As we became interested and found low-effort ways to give to each other, the individual gifts and interests of each team member came through and we were able to conceive of and explore more viewpoints than would have otherwise taken place if we each felt less comfortable. Each team that we had the privilege to hear from in our plenary sessions had authorizers with different styles and problems of different dimensions. The methodology of PDIA was fruitfully applied in each case so long as the team was able to work together and stay engaged. Acts of kindness helped our group in particular to have a floor of kindness and goodwill. The iterative nature of PDIA helped us to remain humble and productive each week. The idea of a design space mapping what works and what is possible, was germane to each problem and helped us orient and steer towards fruitful entry points.

4. You will not solve the problem in 8 weeks. Neither is that the objective of the course. The issues we work in are by nature complex and very hard to solve. The aim of the PDIA method in this course is to arrive at realistic initial action steps upon which the authorizer can build through iteration and reflection. In that sense, it is more important to focus on the feasibility of entry points and initial actions towards meaningful progress than on the expected end result of the process.

Watch the video and view the slides of the PDIA in Action event held in June 2021.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2021. These are their learning journey stories.