written by Matt Andrews

We at the Building State Capability program (BSC) have been working directly with governments for over a decade now; focused on helping agents in those governments build their capability to deliver for citizens and society.

We are not consultants. We do not write purely academic papers, offer technical advice, or work in other traditional consultant ways. Rather, we ask the authorizers we are working with in the governments to nominate problems they care about and appoint their own teams to work on those problems. We then work with the teams regularly (often weekly) to learn their way through their problems, to new, locally defined solutions. The teams do the work, gain from the learning, and achieve the progress. This is how they grow their capability and make progress in improving delivery to their citizens and society.

The methodology we employ is called Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA). It is a simple management approach that helps organizations solve specific complex problems and build their capability to solve other complex problems in the process.

Some people ask if we are like delivery units. The answer is no.

I am going to talk here about delivery units I have worked with. I don’t want to say I have seen or worked with all these units, so I am sure some readers will take issue with my generalizations, but this is based upon my experience.

Delivery units tend to employ outsiders (and sometimes outside consulting firms) to take charge of ‘delivering’ the main objectives of chief executives (presidents or premiers or mayors). The units identify the tasks required to achieve these objectives, and the timeline required for delivery, and use carrots and sticks available in the chief executive’s office to ensure that agents across governments adhere to the timelines.

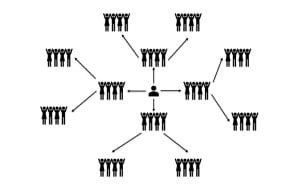

It is very much a downward hierarchical model or plan and control, as in the picture below.

I have seen these units help to deliver a number of things; lower waiting times in hospital lines, more responsive ambulance services, even faster construction of roads and other infrastructure. These and other ‘delivery unit successes’ all tend to be in areas in which the literature calls ‘complicated challenges’ (where we know the answer to the challenge, can plan it out, and ensure implementation by getting key agents to follow the plan).

I have seen the delivery unit model struggle in delivering other things, however; like better quality schooling, or improved work relationships in hospitals, or diversification in exports, or new foreign investment, and more. These are what the literature calls ‘complex challenges’ (where we don’t really know the solutions, which are always context specific, and can thus not plan out a course of action, and where the path to success requires taking risks and trying and learning and allowing for the emergence of new ideas and capabilities).

I have also seen delivery units compromise the capabilities of governments to sustain solutions, because of animosity created between career administrative staff (who believe they should be the ones delivering) and the short-term staff and/or outsiders in delivery units (who like to see themselves as the deliverers). Partly because of the animosity I see between the regular administrative entities and delivery units, I commonly find that the delivery successes are expensive one-off events—there is no long term capability built into the administration to ensure that the successes continue, or to create a broader gain in delivery performance.

PDIA allows for a better way; to build system capability and address complex issues.

My biggest concerns about delivery units, given these observations, are three fold:

- They don’t provide an organizational solution to addressing complex challenges, which are the challenges most governments struggle with most;

- They do not provide a mechanism to build organizational capability; and

- They create strife and tension between chief executives and the career administration that chief executives should be working with and through (after all, these are the people hired and paid to serve the public).

We have found that our PDIA methodology addresses these concerns. The method fosters a learning approach that is well suited to addressing complex challenges. The method is explicitly focused on building capabilities in governments, so that these governments can do better by themselves in short order. The method also helps to build relationships across and within government and between government and other actors (business, civil society, citizens and whoever else needs to work together to solve problems).

One of the keys of the PDIA approach is that outsiders (including those who might be considered to work in a delivery unit) are facilitating a new way of working by insiders, not doing the work or telling people what to do. Another key is that the new way of working is simple, and easily replicated, and does thus not require ongoing outsider ‘expertise’.

We have been helping a newly formed unit in the Honduran Presidency apply PDIA in its work with other line ministries, to be a ‘Delivery Facilitation’ group and not a ‘Delivery Unit’. The team has been in place for six months now, and just finished working on seven problems with seven teams across government. The progress is significant, and the relationships that have been built are lasting, and the capabilities that have been established are wide and deep.

The model of engagement looks something like this, where the president is at the center of the delivery machine (the administration) which grows its capability to deliver by learning how to solve complex challenges through week by week action. Members of the delivery facilitation unit sit in as coaches for multi-agency teams of inside agents (which could also include members of the private sector and civil society). The work—and credit for work—is done by career administrators with active authorization from their ministers and other authorizers.

We will be posting stories from all of these teams over the next few months (using their own words, as their voice is what really counts). Here are some of the achievements they have made in the last six months include:

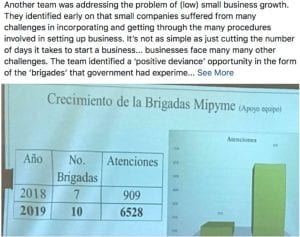

- Ramping up the delivery of small business services through multi-agency brigades that visit towns and villages to make services accessible to all (only 4 brigades had been run before the work began, involving less than a handful of agencies and addressing a few hundred service needs…but the team—coached by a member of the delivery facilitation unit—managed to inspire over fifteen agencies to join the process, run 13 brigades in 6 months, and address over 7,000 small business service delivery needs…)

- Holding various marketing initiatives in two key tourist destinations, to attract new tourists; and working with local private vendors, local governments and security officials to address practical problems undermining growth in these destinations…)

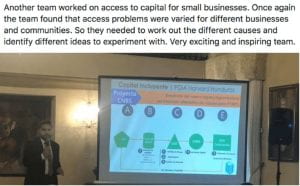

- Building relationships between banks and local rural organizations to make credit available for small business operators in under-resourced areas of the countries; initiating a pilot for such funding. Also, creating the space for new innovative financing options for small businesses (by passing laws and building collaborative relationships) through new market mechanisms.

- Learning quickly about which new agro-industry products offer the greatest potential for growth and working with farmers, bankers, and processors to create a pilot intervention to address bottlenecks and impediments to growth in the plantain sector (where these issues included access to finance and collection and mobilization of local production). The intervention promises to increase local production, help alleviate import needs in the sector, and allow local processors to consider exporting products.

- Developing a range of new systems and other mechanisms to streamline permitting and regulatory agencies—including those providing health and sanitation permits and revenue administration—to improve service performance to citizens and businesses. Also improving human resource management mechanisms in these agencies to ensure better interaction between staff in the agencies and the citizens and businesses served.

- Coordinating the collection, sharing and use of data on electricity provision, access, and costs to ensure an industry-wide evidence-based approach to policy making in the sector (including using evidence to pin point the locations associated with greatest losses, and using evidence to identify the main debtors, and more).

- Learning how to communicate service delivery stories to the public, in paper and video and more; and producing a number of these stories.

I think the experience here is a game changer; it shows that you can have a centrally located group—that brings the authority of the chief executive—working hand-in-hand with the rest of the administration to address complex challenges. In partnership. And producing new, sustainable capabilities (working processes, technical know-how, connections and relationships, and more).

Here are some photos and screen shots of my Facebook posts from Honduras in the last few months … it has been a pleasure and privilege working with these amazing administrators.