written by Lant Pritchett

Improving “accountability” has been a popular agenda for improving public sector performance for some time, and I have promoted accountability as a key to effectiveness myself. In reviewing Dan Honig’s new book, Navigation by Judgment: Why and When Top Down Management of Foreign Aid Doesn’t Work, I want to make a key distinction between account based and accounting based accountability. The fundamental notion of accountability is an account, which is a narrative, a story we tell to those to whom we feel we owe a justification (which can included both authorizers who have provided us with resources and levers to act, professional and occupations peers with whom we share identify and seek approval, and those on behalf we were supposed to have acted, and social peers) about why what we did was the right thing to do (or not) in the circumstances to advance the shared objectives and within the accepted norms. Our account may have some hard numbers and data—what I call “accounting”—but the fundamental issue is the account.

The question is whether accountability can be fully exhausted by accounting. With Moore’s law increasing by orders of magnitude the power to do transmit series of zeroes and ones (information in the Shannon information theory sense) it is increasingly asserted accountability can be reduced to hard, objective, computer storable, numbers and that technology will help governments improve accountability.

Dan Honig’s book asks the question of whether development agencies can be successful with accounting based accountability of the type that large, top-down, bureaucracies favor or whether account based accountability needs to be rehabilitated, emphasized, and encouraged. His argument is that for projects that are complex (not just complicated) and in country and local situations which are fluid and unpredictable, the standard bureaucratic accounting accountability will fail. But allowing the actors of the development agency to Navigate by Judgment, and hence as organizations rely on account based accountability, can succeed where top-down will fail.

The historical sweep of large scale organizations, development and development agencies

The rise of large hierarchical organizations in the private and public sectors is, in many ways, the story of the 20th century. In The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business and Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism the business historian Alfred Chandler charted the transition from owner-operated firms to managerial capitalism. The firms that first took advantage of the opportunities for mass scale in production and distribution in railroads, oil, automobiles, chemicals, consumer goods, retailing became household names that dominated their industries for decades (or more, the second largest industrial firm in 1912 was Standard Oil of New Jersey an its direct descendant is ExxonMobil, still among the largest). Chandler emphasizes that this new managerial capitalism required a new array of techniques and one of those was the developing of accounting.

Similarly in the public sector the 20th century saw the rise of large scale organizations and a shift from “craft” production of public services to large, centralized, bureaucratically or “professionally” managed organizations. Daniel Carpenter’s The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovations in Executive Agencies, 1862-1928 tells the history, during that same period, of how the US Post Office and the Department of Agriculture acquired the organizational structure and political autonomy for action they did. As larger firms drove out smaller firms so too these new larger bureaucracies did not move into domains where nothing was being done—in the army, policing, schooling (e.g. Tyack The One Best System), property rights enforcement (de Soto The Mystery of Capital), and environmental management (e.g. Hays Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency) the large bureaucracies drive out or, more often, consolidated pre-existing smaller, craft-like, local “folk” practices into the new top-down “formula” bureaucracies.

The idea of “development” was born in and of the post World War II era in which de-colonialization was rapidly producing newly sovereign states. The idea that the process of “development” was the accelerated transformation of new states–whose economic and political transitions had been deliberately impeded under colonialism—into “modern” states with large scale industrial firms in basic industry and national Weberian bureaucracies was impossible to resist. (In part, I would argue because of awe from the unprecedented scale and efficacy that the modern, professionally-led, bureaucratically managed, armed forces of both victors and vanquished went at their terrible business. Who could have lived through World War II and doubt the power—for good or ill–of the modern organization?). But this “modern” was not written on a blank slate but was often a self-conscious attempt to overwrite or erase the existing local practices.

And tools were created to meet the task, since the new national and supra-national were embedded in the modern states and intended to accelerate the onset of modern in the new nations, it is only natural that the agencies of development from the UN agencies to the World Bank to the regional development banks to the bi-lateral aid agencies of the OECD countries should take the form of “high modern” (a la Scott) bureaucracies. The organizations, by and large, attempt to accomplish their mission using the standard methods and control structures of large organizations.

Now, while causation is impossible to parse, the “development era” had produced truly stunning accomplishments in improving human well-being (e.g. Hans Rosling’s Factfulness). In 1960, 87 percent of adults in the developing world had not completed primary school, today only about 3 percent of children will never go to school. Life expectancy has increased more in the last 60 years than the previous 6,000. Women (and couples) have dramatically reduced fertility and have fewer, healthier and more schooled children. Absolute, low-bar, material poverty as measured by the “dollar a day” standard has fallen from well over 70 percent of the world’s population in 1950 to something like 10 percent today.

But, success of large scale organizations, in the public sector and in development, has always been interspersed with failure. Anyone who has worked in development for any length of time can rattle off a long list of development projects that failed. Either they failed to even achieve implementation and do anything at all, or the implemented project failed to improve outcomes, or worse, the implemented project had unforeseen consequences such that the net impact was negative. In the development organization I know best, the World Bank (where I worked, off and on, between 1986 and 2007), it is not as if these failures where unreported or unacknowledged—every project had some type of ex post evaluation of its success or failure. There was a constant stream of “lessons learned” from project failures at the sector and the organizational level. But nearly always the “solution” was another policy or process to be implemented with the same “top down” compliance mentality of accounting accountability.

The question that has increasingly faced development and development agencies is what to do when “the solution”—the formal top-down bureaucracy—is the problem?

There has always been a counter-narrative to the triumph of the bureaucracy and large scale organization.

Even among firms in a purely market driven economy private sector often big isn’t better. Think of the last time you went to a dentist. If it was in the USA it almost certainly was not a big firm of dentists. In 2010, 59 percent of dentists practiced alone and 86 percent were in dentist owned practices not corporations. Dentists are not alone in being alone, many professionals, artists, and highly skilled craftsmen work in very small practices compared to the national market or compared to a typical large industrial or retail firm. The 25th largest firm by employment in the USA employs around 250,000 people. The largest law firms in the USA today employs less than 2,000 attorneys—1000 times smaller. The market share of Harvard in US undergraduate education is not 20 percent or 2 percent or even .2 percent but only .02 percent—Harvard enrolls only about 4,500 undergraduates of 22.4 million degree seeking students. Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences has only 574 total tenured faculty.

James Scott’s Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed lays out the case that often since the state can only “see” in “thin” (in the sense of Clifford Geertz) ways the state, when it acts, often reduces the reality of human existence, both as individuals and socially, to levels that fail to capture the “thick” and “complex emergent” nature of human action and human social interactions. Scott argues for metis over techne: practical wisdom over “scientific” knowledge.

Activity types, design mismatch, and account versus accounting accountability

A key difference between the private and public sectors is that in the private sector the organizational size and structure can be determined by the nature of the activity. There are economies of scale and economies of scope or coordination across activities that lead to bigger organizations covering more stages of the value added process that lead to organizations of larger size. Against those are the diseconomies of scale of being to manage more and more people. The trade-offs lead to the wide variety of sizes of firms and the variety of contracting amongst organizations we observe. For instance, when there are economies of scale in some parts of the value chain but not in others organizations forms like “franchising” emerge that split functions between the corporation that handles elements with economies of scale and the owner/franchisee who handles the local activities.

The public sector, for reasons bad and good (and the good ones go very analytically deep and are, in a sense, intractable) has a strong tendency to adopt an organizational form that resembles a Weberian bureaucracy no matter what it does. When the public sector is delivering the mail—the prototypical “logistical” activity for which accounting based accountability works well—it looks, organizationally, a lot like the private sector looks when it delivers the mail. The large companies that deliver packages—FedEx, UPS—do the same logistics in roughly the same ways, just better.

But where governments try and do things that are not, in their nature, logistical and have few economies of scale or scope—like running a school—they also tend to do those activities in large top-down organizations.

In this case there is “design mismatch.” One of the reasons professional services firms (e.g. dentists, doctors (until quite recently), lawyers, architects, designers), colleges and universities, and creative types (e.g. illustrators, actors) or high-end services (e.g. named restaurants) tend to be self-employed or in small forms (relative to the national or even local market) is that quality is both essential to the value and is relatively hard to observe. These are activities that, in their very nature, require account based accountability and accounting is scalable in a way that accounts are not.

Are development agencies delivering the mail or producing high-end professional services?

Back to Professor Honig’s book. His basic argument is that due to political pressures many development agencies have been driven into accounting based accountability but to do development well, especially in the country environments in which development assistance is most needed, development agencies need account based accountability.

I suspect every person who has actually worked on the operational end of development assistance–actually delivering the projects, programs and work plans—recognizes this distinction immediately. They are caught between a front-office that wants them to deliver a specific set of quantifiable targets decided and planned years in advance (and to do so “cost effectively” to deliver “value for money”) and a local reality in which real development progress requires an experimental, adaptive, locally tailored approach in which they must “navigate by judgment.”

Professor Honig gives a great example contrasting two agencies (USAID and DFID) approach in the same country to the same goal: building the public financial management capability of municipal governments in South Africa. Given its politics and organizational constraints USAID has to adopt an accounting based approach for which the deliverable is “person training sessions completed.” This can be counted exactly but not even those implementing the program think it is really making a difference and everyone: USAID on-the-ground person, the municipal governments, the trainers and trainees see this as going through the motions. In contrast, the DFID project gives the development agent pretty considerable flexibility in how to help (and which) municipalities build capability. This means the DFID report is an account (with some accounting of course): “This is what I did and why” meant to be assessed by others who themselves can form a judgment on whether the actions were appropriate to the task at hand and circumstances.

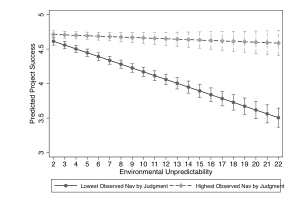

But, beyond that, Professor Honig has created a massive data set on project performance across a larger number of agencies doing projects in a large number of countries and the result of those years of work is a killer figure. This shows that in fixed, predictable, environments the top-down accounting accountability can deliver but, as the context gets more fluid and less predictable the agencies that allow their implementing, on the ground agents to be flexible and use account based accountability continue to have similar performance and hence are robust to unpredictability but for the top-down agencies performance deteriorates as the environment gets less predictable as the design mismatch between the need for flexibility and rapid response to changing circumstances and strict accounting accountability impedes effectiveness.

Source: Honig (2018)

While some goals of development agencies can be, and have been, achieved with (near) purely logistical activities—e.g. vaccinations against childhood diseases—for the most part the easy bits of development have been done. Developing countries and development agencies are now facing “implementation intensive” or “wicked hard” challenges. As Albert Einstein once put it: “We cannot solve our problems using the same thinking we used when we created them.”

Doing development is not delivering the mail. The idea that the 21st century challenges developing countries faced can be solved by making development agencies more like early 20th century top-down bureaucracies by strengthening the top-down accounting and ignoring the need for an account from on-the-ground experts is odd, at best. Professor Honig shows the need for development organizations to have account based accountability to make progress on complex problems in difficult circumstances.