Guest blog by Achref Aouadi, Catalina Reyes Villegas, Gabriela Dutra, Mustafa Rasheed

As we sat in our first PDIA class, we had no idea how experiential the course would be. We knew we would be part of a team working on a problem, but we did not know which one. Options ranged from transportation in New Orleans to access to outer space in Saudi Arabia. Our team came together with the aim of contributing to the understanding of the problem of malnutrition in Angola.

At the time, we knew nothing about the topic. Soon, we understood that malnutrition could take many forms and that we wanted to focus on chronic malnutrition. This condition, also known as stunting, is a pressing issue in Angola, affecting 37.6% of children under the age of five. Such a high rate of stunting, places the country as the 17th worst affected among 152 nations. Stunting is believed to be irreversible and has long-term implications on health, cognitive ability, income, and overall, on economic development.

We worked with Sergio Calundungo, our authorizer, who serves on the Social and Economic Council of Angola. His team has been tasked by the President of Angola with devising a strategy that the government should adopt to tackle malnutrition as a means to reduce poverty.

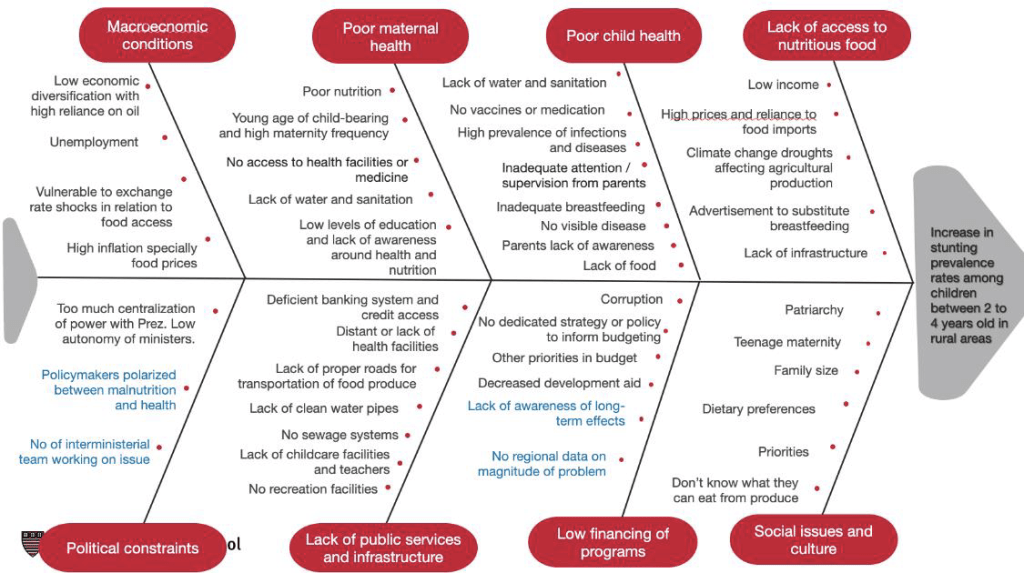

Our first task was to become a team, getting to know each other and drafting a constitution with rules and mechanisms to move the work forward. Our second very important task was to construct and then deconstruct the problem into its potential causes. Understanding what the problem really was, and then building a narrative around why it matters and to whom it should matter was fun. Nonetheless, breaking it down into its potential causes and making a fishbone diagram representing it proved to be much more complex.

Sergio had already built his fishbone version in the past when he took the PDIA course, but he kept it from us because he did not want to bias our work. We were very intrigued by his version and worked hard to build our own in a comprehensive way. We spoke to a UNICEF representative, with other members of NGOs like Ação para o Desenvolvimento Rural e Ambiente, with nutrition experts, and even with former HKS students who live in Luanda.

As a result of our multiple conversations and research, we learned that stunting in Angola is caused by a mix of factors such as lack of access to nutritious food, poor maternal and child health, unstable macroeconomic conditions, insufficient public services and infrastructure, low financing of programs, political constraints, and certain social norms. We also observed multiple isolated efforts from the government, civil society, and international development organizations to tackle the issue, which have so far been ineffective in curbing the growth of stunting rates.

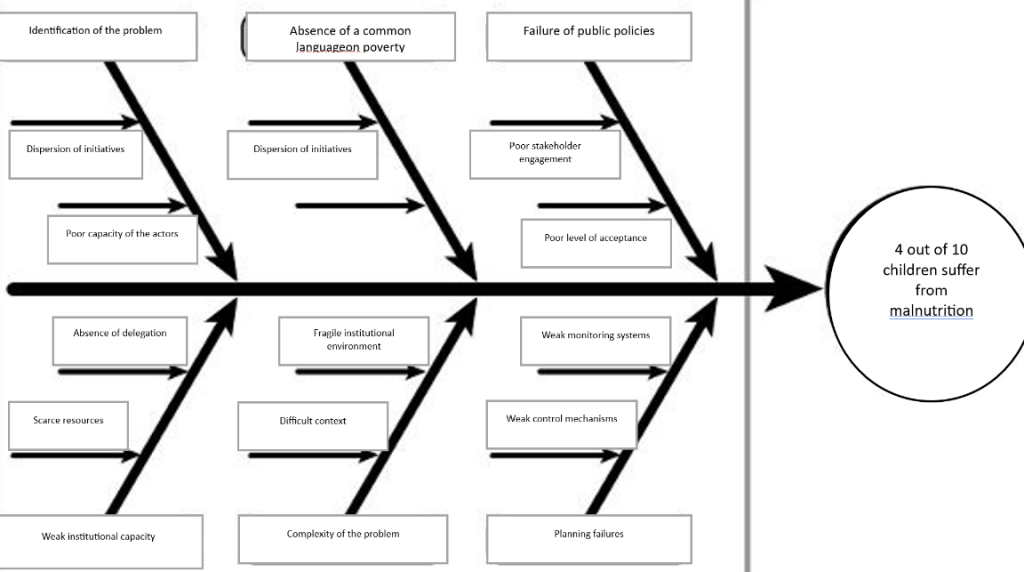

During our third Friday weekly check-in, we presented our deconstructed problem version to Sergio. He was greatly surprised by the number of potential causes we had identified. He highlighted that he hadn’t thought about the problem in that way. During that same meeting, he offered to finally disclose his fishbone version. To our surprise, his main causes were almost all administrative and politically related, an aspect we had only partially considered as a cause that constituted one of our eight fins.

This understanding of the problem was not set in stone. As we moved forward with identifying potential entry points and trying some actual iterations, we constantly adjusted our fishbone diagram to reflect our ongoing learning. This was one of our main learnings, to constantly adjust and adapt based on new discoveries.

While exploring the PDIA methodology, we also gained additional key insights. First, the importance of diagnosing the problem with data. By gathering and analyzing available data, we understood the magnitude and specifics of malnutrition issues across different regions of Angola. Additionally, this process enabled us to identify data gaps that were crucial to inform the strategy our authorizer was building.

We made considerable progress in uncovering new data that helped narrow down the scope of the challenge. Initially, our work focused on diagnosing malnutrition in Angola, a broad issue encompassing a wide range of deficiencies such as wasting, stunting, and obesity. Data helped us understand that the main issue in Angola was stunting, which has been increasing over the last 20 years, contrary to the global decrease and even in comparison with some African countries like Kenya, Ethiopia, and Tanzania, which were improving their indicators.

Additionally, data available in World Bank and UNICEF reports, allowed us to discover that stunting is particularly acute among children aged 2 to 3 years, those living in rural areas, and we found that boys are about 10 percentage points more likely to be stunted than girls. These insights reshaped our understanding of the problem and the narrative in our problem statement. The data-driven approach enabled us to have specific and purposeful discussions with our client and other stakeholders.

Second, we learned that engaging with a diverse range of stakeholders was invaluable. All conversations provided great insights and highlighted the complexity of the issue. Each stakeholder offered a unique perspective, enriching our understanding. However, we were never able to speak directly with local families being affected by malnutrition, which we believe would have further enhanced our work.

The course’s insistence on meeting different people every week allowed us to make progress in identifying key leads and next steps that can help our authorizer continue the work. Through this iterative process, we connected with new people experienced in the issue of malnutrition, both in Angola and other countries, such as Mozambique. Additionally, we were able to discover and present external best practices, like the case of Kenya, which has managed to decrease overall stunting from 35% to 26% between 2008 and 2014.

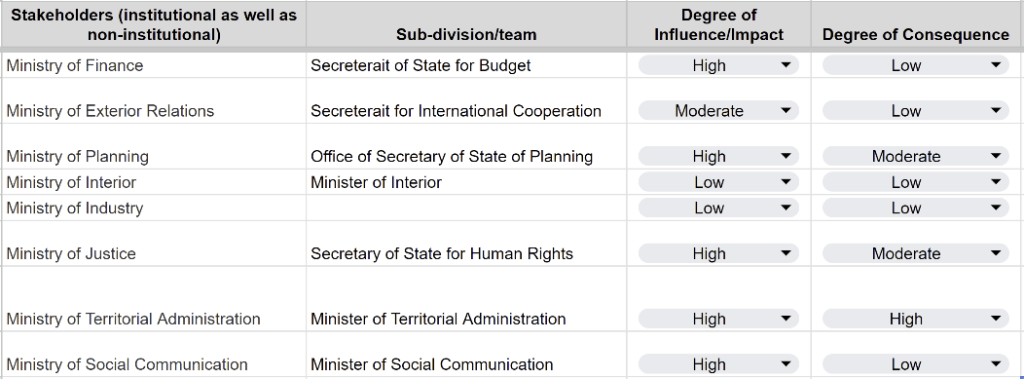

Lastly, we learned that adopting an iterative approach was crucial. Not only did our problem statement and fishbone diagram constantly change, but we were also able to try some strategies to get our authorizer started on what we saw were potential opportunities to experiment and learn. For example, we prompted Sergio to review the problem causes with his team and indicate where they saw an opportunity to make a small change. Additionally, we sat with our authorizer to create a map of actors and determine which stakeholders were the most relevant.

This newly developed mapping has equipped our authorizer with ideas on who must be brought on board to tackle the problem in a holistic manner. We hope this step will prove pivotal in sparking more dialogue across sectors and fostering increased collaboration between various ministries, international organizations, the private sector, and civil society.

The progress we made week by week in gathering data, identifying new leads, and experimenting with activities to encourage Sergio to engage in areas with change space, was encouraging. However, we believe the most significant progress occurred when we heard Sergio describe the issue of stunting as complex and multifaceted during our final presentation. Initially, there was a tendency to view the problem as strictly health-related or social-related, with both perspectives considered mutually exclusive. Now, we are confident that the Angolan team understands that addressing the problem requires a task force that includes sectors such as health, education, agriculture, and social development.

We not only learned but also enjoyed our half-semester work dedicated to chronic malnutrition in Angola. For anyone like us who wants to learn and adopt the PDIA framework in the future, we must emphasize that while understanding the technical aspects is important, even more crucial is the team and the ability to strengthen the bonds throughout the process. A team with rules, commitment, motivation, and mutual understanding can transform small ideas into realities and make the learning process more enriching for all its members. Also, if you’re interested in immersing yourself in this experience, remember to remain curious, celebrate small victories, and trust the process, even in moments where the problem seems too daunting to tackle.

This is a blog series written by students at the Harvard Kennedy School who completed “PDIA in Action: Development Through Facilitated Emergence” (MLD 103) in March 2024. These are their learning journey stories.